They say the camera adds 10 pounds. Does it also add a sudden, terrifying understanding of the abject horror of existence? Phil Noble’s apparently does. The Reuters photographer’s shot of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor leaving Aylsham police station in the back of his Range Rover is an image filled with shock, pain and horror. Noble’s harsh, blinding flash paints Andrew in pink, red and white – his skin is sickly, his eyes are hollow and red like a rat’s. His hands are steepled as if in prayer, like he’s pleading with a higher power for absolution.

Much like the eerily similar 2019 picture of his father, Prince Philip, in a car, this photograph’s composition is one of pure luck. Noble took shots as Mountbatten-Windsor rushed past. Two were blank, two were of the police, one was out of focus. Only this one came out right. Only this one gave us a private glimpse of power crumbling and rotting away in real time.

In the social media and cameraphone age, it’s harder than ever for a single image to stand out, to rise above the visual noise we are bombarded with. That this one has somehow done so shows how important and powerful it is. Whatever precise crimes Mountbatten-Windsor is or isn’t guilty of, in one incredibly fortuitous photo Noble has captured the visceral anguish of having to live with what you’ve done, and contend with its repercussions.

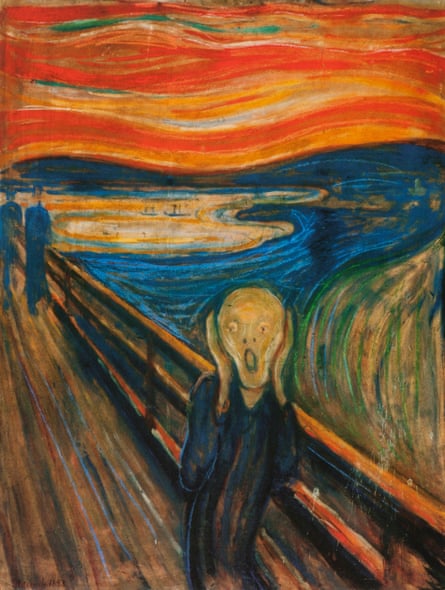

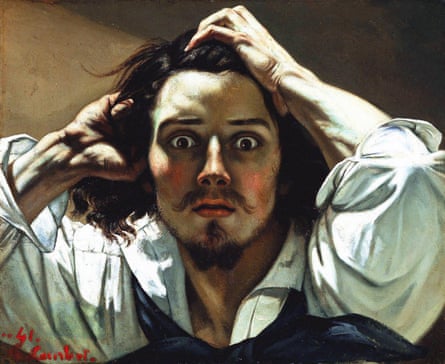

It’s the eyes that do it. They suck you into the photo’s abyss: Mountbatten-Windsor is aghast, stupefied, frozen in wide-eyed dismay and distress. Those red eyes, like two little portals to hell, are not angry or vicious: they are dazed and overwhelmed. They’re the same eyes you see in the anguished howler of Edvard Munch’s The Scream or Gustave Courbet’s Desperate Man.

The same eyes you see over and over in Otto Dix’s Das Krieg series of etchings, where terrified faces glare out of the paper totally unable to make sense of the horrors they have witnessed on the sodden battlefields of the first world war. The figures in Dix’s work are victims, witnesses to trauma, people who have been forever scarred by what they have just survived.

But what viewers – rightly or wrongly – read into this photo isn’t the loss of innocence or the trauma of victimhood. It is guilt and complicity. Something far closer to Francis Bacon’s screaming pope series of paintings of a powerful ecclesiastical figure being consumed by the pain of his own past.

Or, even better, Francisco de Goya’s gothic nightmare Saturn Devouring His Son, a blackened, penumbral vision of a Titan driven to consume his own child because the goddess Gaia prophesied that one of his children would overthrow him. Here, the wide-eyed bewilderment of the central figure speaks of a personal horror, an admission that things have been done, and they can never be undone.

It’s a long way from how royalty has been portrayed in history. All the gold, pomp and circumstance swapped for the end-of-empire, wipe-clean luxury of a Range Rover’s all-white leather interior and the mortifying shame of being the first senior royal to be arrested in modern history.

Images of rulers are controlled, approved, mediated by the rulers themselves. Royals, despots and tyrants don’t allow any old portrait out into wider society. But this isn’t official, this isn’t mediated – it’s a window into a private moment. Royal families around the world must be furious that someone invented telephoto lenses.

Important royal portraits record a small handful of historic truths instead of a wider, more nuanced narrative. Most of us know absolutely nothing about Charles II of Spain, but one glimpse of his huge jaw in Juan Carreño de Miranda’s 17th century portrait of him triggers immediate thoughts of inbreeding and how it was a tool of control, greed and empire. This photo will tell a similar story in the future. It will forever tie the British royal family to the Epstein files and all the grim truths they have revealed.

Will this be their legacy? Will this be how history remembers the royals in the early 21st century? Not as gilded icons, or decorated, powerful leaders standing proud with chests covered in military medals like the royals of old – but as decaying, broken spectres that haunt a decaying, broken nation.

3 hours ago

8

3 hours ago

8