This article was produced in partnership between Floodlight, New York Focus and the Guardian.

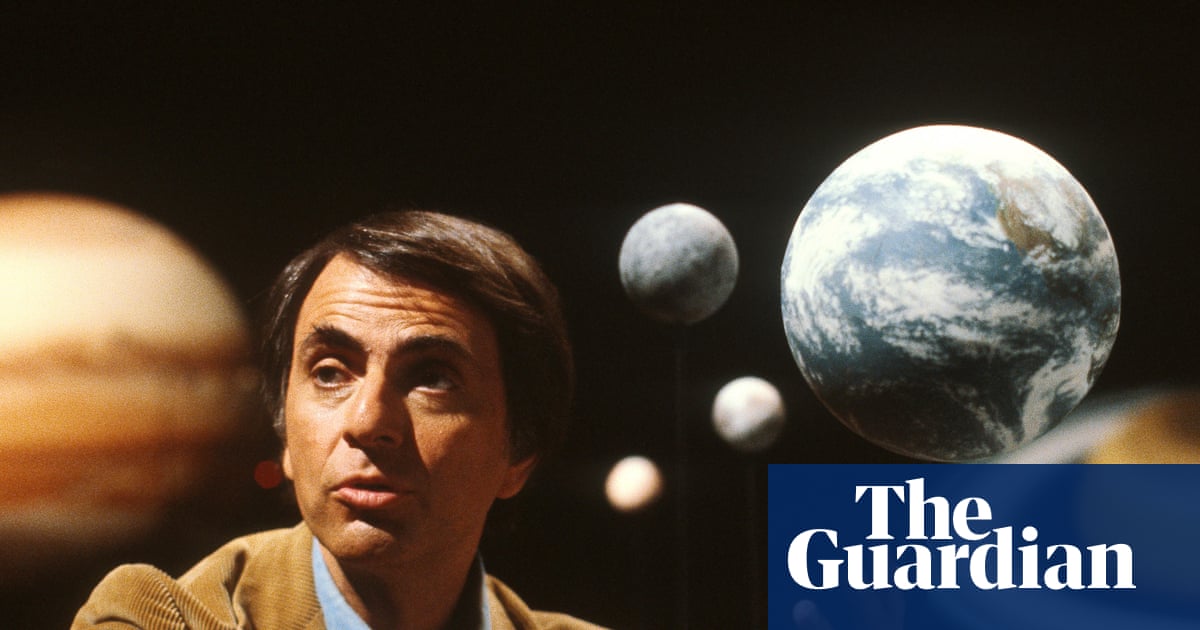

Baba Ndanani has lived in one of New York City’s most flood-prone neighborhoods for more than 20 years, and he knows the risks all too well.

During Hurricane Sandy in 2012, over 5ft of water rushed into his two-story home, which sits directly beside Jamaica Bay in the working class community of Edgemere. He had to swim across the street to higher ground, riding out the rest of the storm in a disabled car surrounded by water.

“I was praying,” Ndanani told Floodlight. “I just wanted to get out, and that was it,” he said.

Afterward, he returned to his decimated house and spent two weeks sleeping atop an overturned refrigerator.

Yet despite his “horrible” experience and a city-run voluntary buyout program to relocate residents of Edgemere, Ndanani says he has no intention of leaving his coastal home.

Instead, Ndanani is among many Edgemere residents still hoping the city will deliver on its decade-old promise to protect the neighborhood from flooding.

“In the other neighborhood(s) they’ve done that, so why is Edgemere different?” Ndanani asked, referring to the city’s ongoing efforts to raise shorelines around Lower Manhattan. “Because we don’t have Wall Street here?”

The lack of flood protections in Edgemere, a minority neighborhood, reflects a wider trend among coastal resiliency efforts currently underway across US cities. In Charleston and Miami and Norfolk, city officials are planning billion-dollar seawalls to protect their wealthy core, but not the vulnerable communities beyond it.

“Neighborhoods like Edgemere will become more and more frequent,” said Veronica Olivotto, a New School researcher who spent months studying flood risk mitigation efforts in Edgemere.

‘We are forgotten here’

With more than 500 miles of waterfront, few US cities are more vulnerable to sea level rise than New York. About 1.3 million New Yorkers live within or directly adjacent to a floodplain, and a recent report estimates more than 80,000 homes could be lost to flooding in the next 15 years.

Ever since Hurricane Sandy delivered a terrifying glimpse of what is to come when it flooded 17% of the city’s land mass, killing 43 people and causing more than $19bn in damage, officials have been scrambling to make New York more resilient to rising waters. The city has begun raising shorelines and installing massive floodgates around Lower Manhattan as part of the so-called Big U, a 10-mile-long U-shaped flood protection system.

The estimated $2.7bn project is among the most ambitious coastal protection efforts in the nation. But for many of New York’s working-class coastal residents, it’s just another city service they aren’t seeing in their neighborhood.

“If they can invest in other communities, raising up the shorelines, putting berms in the communities that’s along the Lower East Side, as well as the Hudson River, why can’t they do the same thing to Edgemere?” Jackie Rogers, an Edgemere resident, asked.

Edgemere was among the hardest hit communities during Hurricane Sandy. A low-lying neighborhood located along the Rockaway peninsula, Edgemere is flanked by the Atlantic Ocean and Jamaica Bay. When the superstorm struck, water rushed in from both sides, filling the streets with nearly 6ft of water.

“The ocean and the bay were one and the same,” Sonja Webber-Bey, an Edgemere resident, said. “So whatever was in your house was the ocean and the bay.”

In response to widespread destruction in the area, the city launched the Resilient Edgemere Community Planning Initiative in 2015. The goals were to reduce flood risks and bring in affordable housing. The city has since upgraded drainage systems, elevated more than 100 homes and rebuilt the boardwalk to fortify Edgemere’s oceanside. But a crucial protection feature that promised to raise the shoreline along the bayside within five years was dropped.

“Edgemere, especially the portion towards the bay, is still highly vulnerable,” Olivotto told Floodlight. “If a superstorm were to happen next month, the same exact issues would occur in Edgemere as they occurred in superstorm Sandy.”

“It’s 13 years since superstorm Sandy, and yet still no flood mitigation on the bayside,” Rogers said. “We are forgotten here.”

‘The city does not have the full resources … ’

“I understand the frustration of Edgemere residents and I think that what we’re talking about with this plan is really challenging compromises,” Michael Sandler, associate commissioner at the NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development, told Floodlight.

“The plan will be a success,” said Sandler, whose agency is responsible for the effort. “I don’t consider the plan to be complete. And I think the plan has taken much longer to implement than we would have preferred.”

Key setbacks, he said, such as “continuity of staffing at the agency” as well as the loss of funding during the Covid-19 pandemic contributed to the delays. Still, Sandler recognizes that Edgemere remains far too vulnerable.

“We’re coming up on the peak of hurricane season right now, and there isn’t a coastal protection feature, and I think that residents in the neighborhood are right to be concerned about what the future looks like,” Sandler said, speaking earlier this fall. He added: “I think that we have invested a lot in the community. We have a lot in the works right now that is coming in terms of community improvements.”

The city now relies on a federal army corps of engineers project to protect Edgemere’s bayside. However, the project has remained in the design phase for years, and with the Trump administration’s posture towards climate change, few in Edgemere expect the project to move forward anytime soon.

“It’s not happening,” Rogers said of the army corps project. “Nobody is looking to do anything along this bay to address the constant flooding of Jamaica Bay.”

Sandler says there is federal funding for the project, and it is moving forward, but he acknowledges residents’ frustration.

“These are really big, complicated projects, and the city does not have the full resources for all of the coastal protection projects that are necessary to protect the city from climate change,” Sandler said. “And we have a partner in the federal government who is overall pulling back from this work and from their financial commitment to resiliency. And so it is a really big challenge for New York City.”

‘Idea of bringing new homes needs to be rethought’

Despite the lack of flood protections, the city has approved construction of new affordable housing towers in Edgemere. All are in or adjacent to floodplains; sea level rise projections show they could be partially underwater by 2100.

Officials stress the city’s need for affordable housing and that apartment towers in Edgemere will be less flood-prone than one- and two-story homes. But Olivotto notes evacuation from Edgemere is tricky, with only one main road and one subway line. “I think the idea of bringing new homes to Edgemere needs to be rethought,” she said.

Bringing more affordable housing to Edgemere continues a nearly century-old tradition of trying to concentrate low-income residents in public housing along the city’s perimeter. What began under the infamous city planner Robert Moses has now resulted in thousands of working-class New Yorkers living in vulnerable floodplains across the city.

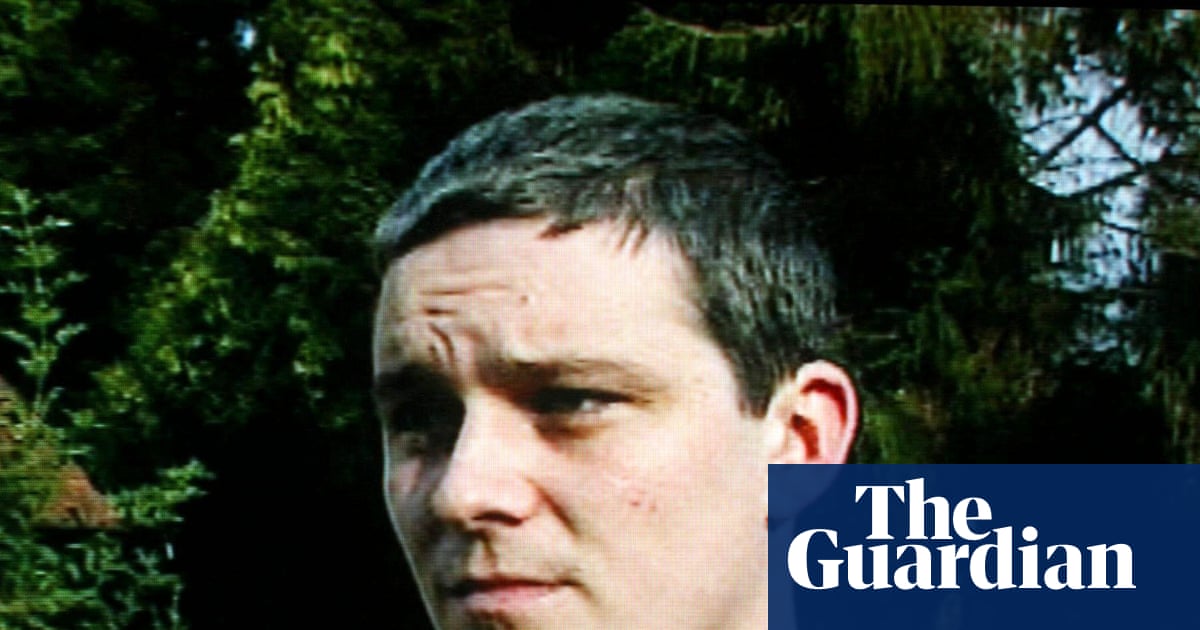

“Nobody ever said that in a couple of years this community would be underwater,” said Rogers, who moved to Edgemere in 2007 through a city-run affordable housing initiative under the administration of the then mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Rogers soon realized flooding wasn’t the only issue in the area. Decades of failed urban renewal projects had left behind dozens of vacant city owned lots strewn throughout the neighborhood that have since become hotspots for illegal dumping. After Hurricane Sandy, Rogers learned the city had plans to increase the number of empty lots in her neighborhood to limit flood damage.

‘We need to think … about the land that’s left behind’

As part of the 2015 Resilient Edgemere plan, the city attempted to relocate some of the community’s most vulnerable residents through a voluntary buyout program.

Officials established a zone along Jamaica Bay where it limited development and offered to buy people’s homes in exchange for moving elsewhere. Ultimately, only seven of the approximately 50 eligible homeowners participated in the buyout program.

“It is still one of the hidden gems in New York City, even with all the vacant lots, with all the mosquitoes. It’s quiet. You can hear yourself think at night,” Rogers said when asked why she and so many residents want to remain in Edgemere.

Others interpreted the buyout program coinciding with new housing developments in the area as a sign the city wants to push out longtime residents.

“I think people feel they just want our land,” said Webber-Bey, who has lived in Edgemere for nearly 50 years, “and then they’re going to build something that’s three or four times as expensive.”

“They’ve been neglected in the past and they see retreat as a new sign that the city just doesn’t want to invest in this neighborhood,” Olivotto said. She added it’s important the city takes steps “to try to regain trust of the citizens of Edgemere”.

Research shows fewer than 10% of Americans who experience a natural disaster consider relocating. For most, it’s simply too difficult to leave the economic, social and cultural networks they’ve built their lives around.

Residents who do take flight tend to be younger, higher income households who can afford to rebuild elsewhere. As a result, those left behind in working-class communities such as Edgemere are often left with fewer resources to guard against future flooding.

“We live from day to day not knowing what a high tide or hurricane’s going to do to this community. It is very scary,” Rogers said. “But by the grace of God, I ain’t going no place.”

Olivotto says Edgemere illustrates how officials managing retreat from an increasingly uninhabitable coastal US “will have to confront the fact that some people cannot move either because they don’t have the financial means or because they feel that this is the place they have always lived”.

She added: “We need to think way more about the land that’s left behind, and the people that are left behind after retreat than we are right now.”

Floodlight is a non-profit newsroom that investigates the powers stalling climate action. Sign up for their newsletter here. New York Focus is an independent non-profit newsroom investigating power in the Empire state. Sign up for their newsletter here.

3 months ago

52

3 months ago

52