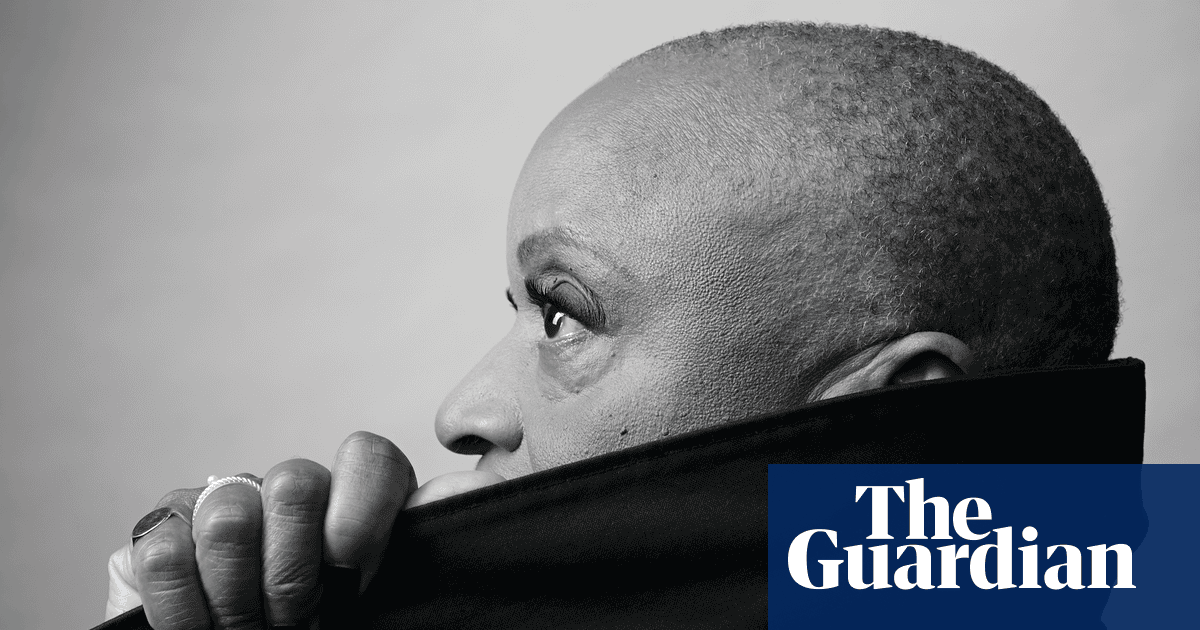

Aasis Subedi, a Bhutanese Nepali refugee, finds himself back in the same Nepal refugee camp he spent part of his youth, once again stateless.

Last month, Subedi and two dozen community members from across the US were deported by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) officers to Bhutan, the tiny Himalayan country where they had never previously set foot. At least four, including Subedi, were immediately rejected by Bhutanese authorities and then expelled to India, where they fled to a refugee camp in Nepal.

“I have nothing right now. They brought us in [to Bhutan] without any documents,” he says from one of the three Beldangi refugee camps in the southeast of Nepal, where he is using his father’s cell phone.

Subedi had been serving jail time for a third-degree felony offense committed in Columbus, Ohio, before he was put on a plane and deported via New Jersey.

Subedi is one of the more than 100,000 Bhutanese Nepalis who fled ethnic cleansing and were made stateless by the Bhutanese government who stripped them of their citizenship rights in the 1980s. Since 2008, more than 90,000 have been resettled in the US.

But the Trump administration has upended life for the community.

“Bhutan is still not safe for our community members to return [to]. It is a matter of putting our lives at risk … Now, people are going through the cycle of being stateless again,” says Robin Gurung of Asian Refugees United.

Several of the deported people are believed to be missing in India.

ICE told Global Press Journal that Subedi was deported under a ‘targeted enforcement operation.’ Green card holders – Subedi is a legal permanent resident – can be deported having been found guilty of a serious crime but only after having the opportunity to plead their case in court and once the US government has shown “clear and convincing evidence” that the person can be deported. US laws forbid the deportation of individuals to countries where their safety may be at risk.

“Most of the folks who have been deported have already served their time. For me, that is the matter of concern,” says Gurung. “They served their time, they were in their communities, providing for their families, their children, and now they are gone.”

Thousands of Bhutanese Nepalis have settled in parts of Ohio and Pennsylvania that faced major economic struggles and population loss due to the 2008 Great Recession. Around 8,000 Bhutanese Nepali people now live in Reynoldsburg, a city outside Columbus, making up around one-fifth of the population.

Along the suburb’s main thoroughfare, East Main Street, Bhutanese Americans have opened up more than 30 businesses ranging from hair salons to restaurants.

“A lot of the community works at local Amazon and FedEx facilities. Those kinds of jobs were very attractive for folks, and the schools in Reynoldsburg are good,” says Bhuwan Pyakurel who came to Reynoldsburg in 2016 and has since become America’s first-ever Nepali-Bhutanese elected official.

“Many of those businesses were closed before we came here [and] we came and revived them. Cricket is a big thing for the Bhutanese community when it wasn’t known here in the past. Now the city is in the process of building a new cricket field.”

While towns and cities across the Sun Belt have grown significantly in recent years, northern states such as Ohio, Pennsylvania and beyond have struggled to retain and attract residents.

As a result, immigrants have played an important role in helping local economies grow, creating a tax base for city authorities and adding vibrancy to a region working to shed its Rust belt past. Next door in Pennsylvania, around 40,000 Bhutanese Nepalis live in the cities of Harrisburg and Lancaster. Harrisburg has lost nearly half of its population since 1950, though in recent years that decline has been halted.

But now a crippling fear has gripped immigrant communities across the country.

Pyakurel, who was elected to Reynoldsburg’s city council in 2019 having lived in a refugee camp in Nepal for 18 years, says he now fields five to ten phone calls a day from worried local Bhutanese Nepali residents, many asking for guidance.

“People are wondering if they should apply for their citizenship or wait for three years, if they should renew certain documentation,” he says. Last month, Palestinian green card holder and Columbia University student Mohsen Mahdawi was detained at a naturalization interview and deportation proceedings against him were enacted. On 30 April, Mahdawi was released.

“Nowadays, I carry my passport with me all the time,” says Pyakurel. “Even though I’m a [city council] representative here, I don’t look like a citizen to many ICE officers.”

Subedi came to the US through a government refugee relocation program in July 2016 and had been living and working as a machine operator in Pennsylvania before his arrest in Columbus last July.

Now 7,700 miles from home, he has little to do but sit all day in the refugee camp, where he lives in a bamboo-made hut – the very same camp he spent the first two years of his life and where his father still lives. The arrival of him and three others deported from the US caused a stir at the camp, which drew the attention of the Nepali police, who detained him for several weeks as his legal status was investigated.

This month, his daughter turns three years old. He says his family has no money to assist him in the refugee camp in part because his wife stopped working when their child was born.

He says he doesn’t know if he’ll be able to come back to the US.

“I want to come back. I have family, my kids,” Subedi says.

“This is the second time we have become a refugee.”

3 months ago

45

3 months ago

45