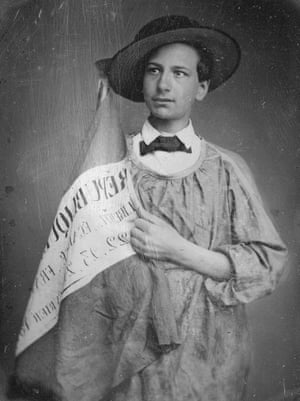

Daguerreotypes are cherished for their eerie clarity, like this one from the 1840s. Unfortunately, achieving such detail required agonizingly long exposure times, from 15 minutes to half an hour, depending on lighting. This required subjects to sit motionless for long periods of time, and various props were employed to keep sitters still and avoid motion blur

Photograph: The Brooklyn Museum

Brainerd’s ‘spy camera’, a box-form apparatus disguised to look like a book, allowed him to move in close without drawing attention to himself. This 1878 image of a longshoreman in Brooklyn’s waterfront district might have been snatched from the pages of Charles Dickens or William Makepeace Thackeray

Photograph: George Bradford Brainerd Photograph Collection, Brooklyn Public Library/Center for Brooklyn History.

A whimsical Kodak promotional image from the early 1900s designed to show that the camera, in this case an early bellows model, was so simple even a child could operate it

Photograph: The Brooklyn Museum

Brainerd often singled out the Soap Fat Man as his first successful ‘instantaneous’ snapshot because he managed to capture his subject ‘walking with his foot off the ground’

Photograph: George Bradford Brainerd Photograph Collection, Brooklyn Public Library/Center for Brooklyn History.

Brainerd had developed his own emulsions, carefully working out the right combination of light-sensitive silver halides suspended in the gelatin binder to coat the glass plates. Brainerd would also devise a mechanical shutter that could click off exposures of at least 1/250 of a second

Photograph: The Brooklyn Museum

During the wet collodion era, the apparatus was still quite bulky and photographic equipment was often hauled up mountainsides by packhorse. At this time, photographers did not use enlargers for printing. Prints were made by contact printing, and to obtain prints of three sizes, the photographer would bring along three different cameras, the largest taking 20x16in plates

Photograph: The Brooklyn Museum

‘I hear America singing,’ wrote fellow Brooklynite Walt Whitman, onetime editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, where he often described the humble lives of immigrants, even paying a visit to Brooklyn’s Fourth Avenue Irish shanties. ‘The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of the girl sewing or washing. Each singing what belongs to him or her and to no one else’

Photograph: George Bradford Brainerd Photograph Collection, Brooklyn Public Library/Center for Brooklyn History

The craze for skating in the Victorian era spawned a few rather odd inventions. One of these was a skating chair – more or less a dining chair armed with runners. Brainerd was almost certainly using one of his surreptitious cameras to capture this image of a woman smiling – a display of emotion unheard of in stiff, formal portrait photography of the time

Photograph: George Bradford Brainerd Photograph Collection, Brooklyn Public Library/Center for Brooklyn History

Dual-lens stereographic cameras such as the one pictured here, which used short focal-length lenses, produced some of the first ‘instantaneous’ images, provided the photographer did not get too close to his subject

Photograph: The Brooklyn Museum

An enchanting view of Victorian New York is preserved in this image showing a broad expanse of cobblestones studded with gas lamps near the statue of Benjamin Franklin opposite City Hall Park, at the intersection of Park Row and the Brooklyn Bridge approach

Photograph: George Bradford Brainerd Photograph Collection, Brooklyn Public Library/Center for Brooklyn History

3 months ago

50

3 months ago

50