Jonathan Watts

A spectacular demonstration by tens of thousands of climate, nature and land activists in Belém this weekend has set the stage for the second week of COP30 negotiations, when organisers hope the energy from the streets can be channeled into the conference halls.

Monday and Tuesday mark the transition to the political phase of the negotiations, when ministers fly in to grapple with the issues that were too thorny for their bureaucrats to handle.

The climate conference got off to a flying start last week with a rapid agreement on the agenda, but then quickly became snarled up in dispute over four subjects: trade, transparency, finance, and how to address the shortfall between the emissions cuts planned by countries and those required to limit global heating to the 1.5C target of the Paris agreement.

Developing countries insist on much higher levels of climate finance from wealthy industrialised countries to assist with the energy transition and compensate for the loss and damage that is already being suffered as a result of global heating.

There have been more fruitful talks on a just transition for those affected by the move to a low-carbon economy, with a big push from the G77 group of countries, China and labour unions to adopt a Belém Action Mechanism on this topic.

For the first time, one draft mentions the “critical minerals” that will be needed for the energy transition. Other strong areas of debate were on adaptation and the need to address climate disinformation, which is recognised as a growing threat.

A fossil fuel phase out is not part of the official Cop30 agenda, but this fundamental issue has been bubbling away throughout the past week, and at a volume that has rarely been heard before. The Brazilian presidency is seeking a space within the process for talks on a roadmap “to accelerate the transition” with strong support from many global south nations and island states that are worst affected by the climate crisis. In an exclusive interview with The Guardian, Brazil’s environment minister Marina Silva said countries should have the “courage” to address the phase-out of fossil fuels, calling the drawing up of a roadmap for it an “ethical” response.

The need for urgency has never been more apparent. Numerous studies, unveiled in Belém, have shown the world has already failed to limit global heating to the Paris Agreement target of 1.5C, continues to put record amounts of warming gases such as methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and has started to pass dangerous tipping points in the Earth System. Over the past year, previous progress has been put into reverse, largely as a result of US president Donald Trump’s backtracking and trade tariffs that slow the spread of clean technologies. if “stated policies” are implemented as planned, the International Energy Agency revealed last week that it expects global warming to reach 2.5C by the end of this century, a tenth of a degree higher than last year’s forecast.

Brazil has yet to conclusively confirm or deny hopes that it will seek a concluding “cover text” to codify any progress achieved at this conference. If parties remain too far apart for that, the host may look for other ways to maintain momentum until next year’s Cop. Where that will take place is on the long list of unresolved issues. Australia and Turkey have been vying for hosting rights since 2022. If they fail to reach an agreement Cop31 could default to Bonn. Wherever it ends up, the host will be working against the clock to get ready with less than a year to go.

Belém faced similar doubts this time last year, but despite sky high accommodation costs and last-minute construction work, it has won many visitors over during the past week. The expected traffic chaos has not materialised. And many participants have expressed delight that indigenous groups and other elements of civil society have been given more space to participate and protest than the past three climate summits in authoritarian nations.

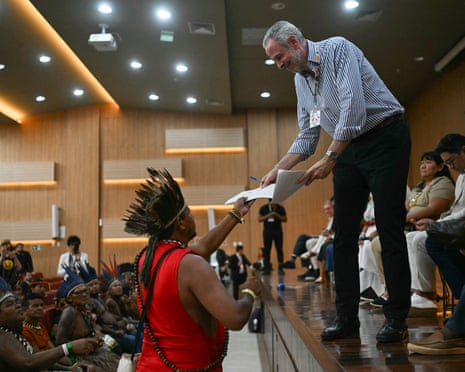

The “People’s Summit”, a series of civil society discussions that has been running in parallel to Cop30, wrapped up on Sunday with a declaration that capitalism was the root cause of the climate and nature crisis. Its demands, including an end to carbon credits and other market-based solutions, were presented to Brazilian environment minister Marina Silva and Cop30 president André Corrêa do Lago, who promised the statement would be noted in the proceedings of the conference.

Nothing remotely as radical is likely to be approved inside the official blue zone of the conference centre this week. But Monday will see several announcements and events related to forests and nature, including a new commitment to support land tenure for indigenous peoples and other traditional communities.

This is a significant step forward, particularly given this is the first summit of its type in the Amazon rainforest. But much more will be needed if forests and other natural biomes are to play a central role in restoring climate stability and planetary abundance.

While much of the attention this week will be on whether Cop30 can initiate the drawing of a roadmap away from the fossil fuel era, the Amazon ought to be as good a place as any to start thinking beyond wind farms and solar panels to where humanity might go next.

Hello, Ajit Niranjan here from Berlin - I’ll be hosting the liveblog this morning and my colleague Nina Lakhani will take over this afternoon.

We’re joined by a team of expert reporters on the ground, who’ll be bringing you the latest as the second week of the 30th UN climate summit kicks off.

3 months ago

64

3 months ago

64