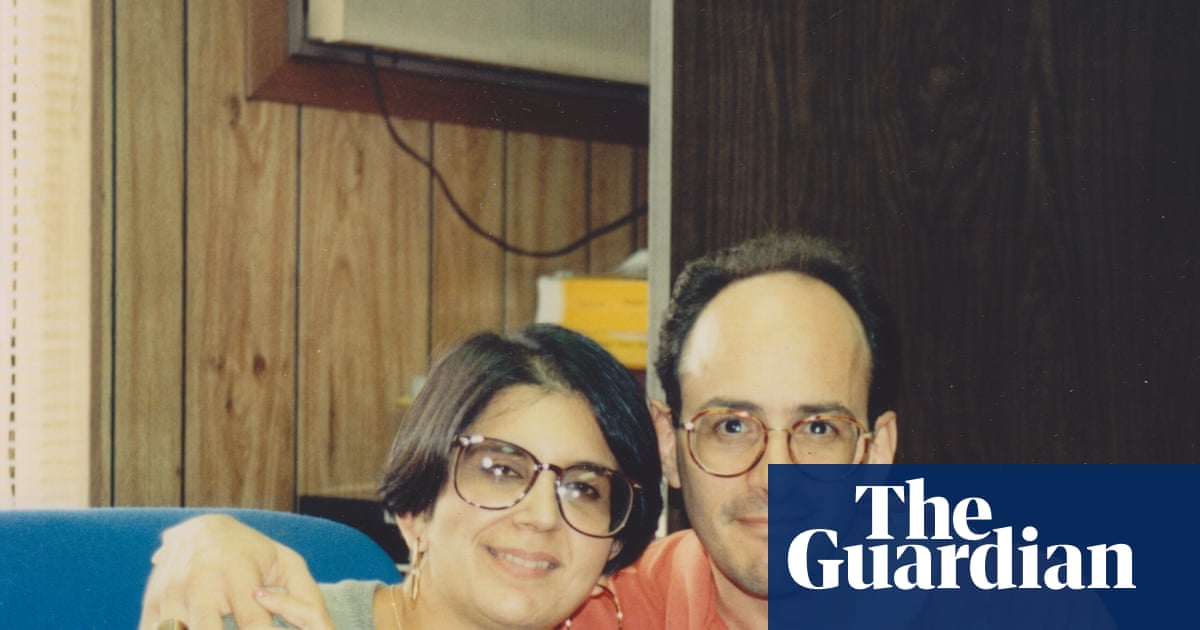

In a last message to her friends, Ifunanya Nwangene wrote: “Please come.”

The 26-year-old singer and former contestant on The Voice Nigeria had been bitten by a snake while asleep in her flat in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, and was in hospital, anxiously awaiting treatment.

Despite rushing to seek care, Nwangene died a few hours after being bitten, as her friend waited at a pharmacy to buy the antivenom she needed.

As the news of her death on 31 January has spread, it has sparked a fierce row over the ready availability of drugs needed to treat deadly snakebites in Nigeria’s hospitals.

Nwangene, also known by her stage name Nanyah, had appeared on The Voice Nigeria in 2021 and was preparing for her first solo concert later this year according to friends. In a tribute, her choir said she was a rising star “on the cusp of sharing her incredible talent with the world”.

Snakebites kill one person every five minutes globally – up to 138,000 every year, and leave 400,000 more with permanent disabilities. Many cases and deaths are thought to go unrecorded, particularly where victims seek care from traditional healers rather than hospitals.

Campaigners say there is insufficient funding to meet the UN’s goals, set in 2019, of halving deaths and disabilities from snakebites by 2030, and research investment is “precarious”. Snakebite envenoming is classed as a neglected tropical disease.

According to the World Health Organization, most deaths from snakebites are “entirely preventable” if safe and effective antivenoms are available and administered swiftly. They are in the WHO’s list of essential medicines, and global health officials say they “should be part of any primary healthcare package where snake bites occur”.

Nwangene said she was woken up at about 8.30am by a bite on her wrist from a grey snake. Two snakes were later found in her apartment, one, a medium-sized cobra, in her bedroom.

Nigeria has 29 species of snake, of which 41% are venomous. Shortages of antivenom due to manufacturing problems have been reported across Africa, along with quality concerns about some products.

The first hospital in Abuja that Nwangene went to, there was no antivenom available, according to social media posts by her brother.

She then went to the Federal medical centre (FMC) where she received treatment including polyvalent snake antivenom, but died after what that hospital has described as “severe neurotoxic complications from the snakebite” and a “sudden deterioration”.

Sam Ezugwu, director of Amemuso choir, of which Nwangene was a member, had rushed to the hospital after she asked for help in the choir’s WhatsApp group. He said doctors at the FMC said “they urgently needed neostigmine [a drug used in combination with antivenoms in snakebite cases] and additional doses of the medication already administered, explaining that the hospital had exhausted its supply”.

But while he was at a nearby pharmacy purchasing the drug, Nwangene died.

“We returned to the hospital to find Ifunanya’s lifeless body on the bed,” he said in a statement on the choir’s Facebook page. “We cried, prayed, screamed, but she could no longer hear us.”

A poll of 904 healthcare workers across Brazil, Nigeria, India and Indonesia by the Strike Out Snakebite global initiative, published last month, found 99% reported challenges with antivenom administration.

They included a lack of training on how to monitor signs of progression, poor infrastructure and inadequate equipment, and daily shortages of antivenom – the shortages were reported by more than a third of the healthcare workers.

Elhadj As Sy, chancellor of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and co-chair of the Global Snakebite Taskforce, said: “Many solutions exist, but we need political will and bold commitments from partners and investors to turn the tide on this preventable yet devastating neglected tropical disease.

“Snakebite must no longer be overlooked or underfunded by the international community. It is time for action – not sympathy, not statements, but action worthy of the scale of this crisis.”

The FMC has denied that there was a lack of appropriate antivenom at its site. In a statement it said: “Our medical staff provided immediate and appropriate treatment, including resuscitation efforts, intravenous fluids, intranasal oxygen, and the administration of polyvalent snake antivenom … We stand by the quality of care and dedication our team demonstrates daily. The claims of non-availability of anti-snake venom and inadequate response are unfounded and do not reflect the reality of the situation.”

4 weeks ago

23

4 weeks ago

23