On a humid evening in Dakar, an Irish jig echoes through the country’s air-conditioned national theatre. The breathy, woody sound of the west African Fula flute brings a different cadence to the traditional tune. Actors dance across the stage, their peasant costumes stitched from African fabrics.

The dialogue is in French, the playwright is Irish and the players are Senegalese. Set in 1833, Brian Friel’s Translations – one of Ireland’s most celebrated modern plays – follows British soldiers sent to rural Donegal to translate Gaelic placenames into English.

The encounters between villagers and soldiers become a way to explore colonial power, language and identity. It is a story that resonated deeply with the cast in Senegal.

“I was really surprised to learn that Ireland, a European country, had also experienced colonisation,” says David Diémé, who plays the Irish translator, Owen.

Staged by the Dakar-based theatre company Brrr Production in late September, the play’s debut is being followed by a tour of schools and universities across the capital before opening to the public early next year.

Since its 1980 premiere in Derry, Translations has been reimagined across the world, from apartheid South Africa to Māori and Ukrainian productions.

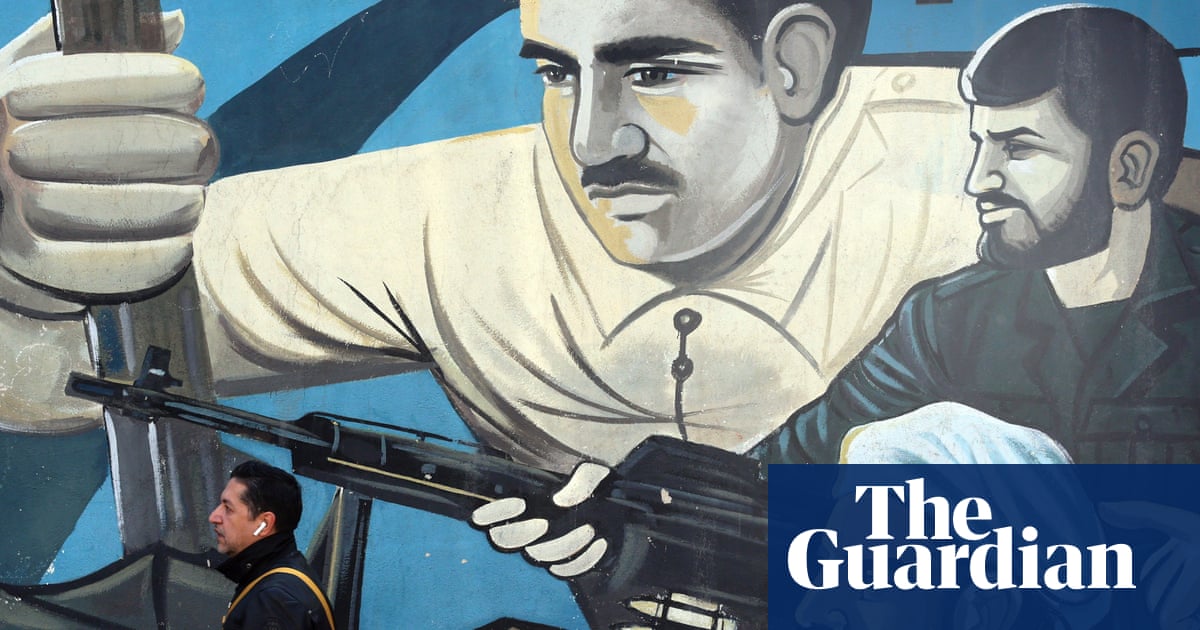

Its arrival in west Africa comes amid renewed debates over the former colonial power’s sphere of influence, Françafrique, as the region’s nations distance themselves from Paris.

Elected in April 2024 on a promise to defend “the integrity of the territory and national independence”, President Bassirou Diomaye Faye has since closed key military bases, joining Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad in expelling French troops.

“There have been changes recently felt almost throughout Africa,” says Ass Niang, who plays Hugh, an Irish-language “hedge-school” teacher in Donegal. “It’s as if the play were written for today.”

Colonial powers spent centuries competing for trade in Senegal before it became a French colony in the late 19th century. It gained independence in 1960, but the vestiges of colonialism linger.

Both Ireland and Senegal “share an Atlantic perspective … a post-colonial experience,” says Shane Keenan, chargé d’affaires at the Irish embassy in Dakar. “And in particular both have a significant experience of outward migration.

“It’s a study of the nuances and intricacies of the relationships between the local and the outside.”

Friel’s dramatic conceit means the original play is in English, though the Irish villagers are meant to be speaking their own language.

El Hadji Abdoulaye Sall, a professor of theatre at Dakar’s Cheikh Anta Diop University, relates this struggle to Senegal’s own linguistic history.

Explaining how French was “a language of prestige”, the professor says: “First, [it] was colonial, reserved for a small elite; the official language, the language of administration … but the real linguistic identity of the country remains Wolof.”

Using the French translation, the language is rich with 19th-century idioms and agricultural terms, says Brrr Production’s French-born director, Bérengère Brooks.

“I thought the French would be too difficult. But they worked for a month, four sessions a week,” she says proudly.

With Wolof being the first language for most people in Senegal, some cast members did not study French beyond primary school.

after newsletter promotion

“They forced us to learn French when we were little. We weren’t even allowed to speak Wolof or Diola in class or in the schoolyard,” says Diémé.

In Act II, over bottles of the home-brewed Irish spirit poitín, Owen and Lt Yolland pore over a map and discuss the anglicisation of Irish names. The parallels with Senegal struck many cast members, many of whom grew up on streets still bearing colonial names. French colonial authorities renamed Ndakaaru to Dakar in 1857.

Adama Diatta, a Senegalese activist, campaigns to change street names in Dakar as part of a drive to “decolonise” and untangle Senegal from its “forced marriage” to France.

He recalls a bridge in Saint-Louis – the capital of French colonial Senegal for more than 200 years – named after Louis Faidherbe, a 19th-century French governor who led brutal military campaigns in the region.

“If we really explained to people who this man was and what he did … do you think anyone would accept that a single brick of a building bears his name?” Diatta says.

The love between Yolland – a British soldier who believes he could love Ireland – and Máire, an Irish girl eager to learn English and emigrate, embodies the tangled loyalties that linger after colonial rule.

“For me, playing the role of Máire has great significance,” says Aminata Diol. “Being a native of Saint-Louis, I grew up hearing about the mulatto women – the signares – who lived through similar stories of relationships with the colonisers of that era.”

The characters grapple with the tension between modernity and tradition – Manus refuses to speak English, while young Máire sees learning it as her path to a new life in the US.

In Senegal, echoes of this tension remain, with France’s influence still visible – from the West African CFA franc (which is pegged to the euro) to the French supermarkets and businesses that line the streets.

Breandán Mac Suibhne, a historian at the University of Galway, believes Translations is a “disavowal of a simple black-and-white narrative”.

“It bears the complexity of colonial situations … there is choice as well as coercion,” he says.

Mac Suibhne says he can think of nowhere better to stage the play – and nowhere it would be better received: “Is west Africa all that far from the west of Ireland?”

3 months ago

55

3 months ago

55