For decades, guerrilla communist warfare has raged deep in India’s jungles. What began as an uprising in the 1960s, fuelled by inequality and discontent among the poorest, is now a fully fledged Maoist armed struggle vowing to overthrow the Indian state.

But after decades of insurgency and a corresponding state-led crackdown that has left almost 12,000 civilians, militants and security personnel dead, India’s home minister Amit Shah gave a clear-cut deadline earlier this year; the Maoist insurgency would be “completely eradicated” by March 2026.

Yet activists, lawyers and former officials have alleged that the operation has come at the cost of human rights abuses and loss of civilian life. They have also questioned the government’s motives as well as whether it can truly erase the ideologically driven movement.

Widely known as the Naxalites, a name taken from the West Bengal village where the first peasant rebellion took place, the movement follows the Marxist-Leninist ideology of class struggle and agrarian revolution and the philosophy, taken from the Chinese communist leader Chairman Mao, of achieving this through guerrilla armed struggle.

The Naxalite cadre has largely been drawn from two of the most marginalised and oppressed groups in India: adivasis, the tribal Indigenous people who largely live in the forests and jungles, and Dalits, the lowest caste previously referred to as untouchables.

The militant insurgency has surged at various intervals over the past half century. At its peak in the early 2000s it controlled large swathes of the country, known as the “red corridor” which stretched from the Telangana-Andhra Pradesh border in southern India, right across the central states of Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Maharashtra, Jharkhand and up to West Bengal, and had more than 30,000 foot soldiers.

Now, however, the number of active Naxalite fighters is estimated to be just 500, operating in limited districts, who pitch their fight as a David and Goliath struggle.

‘A killing spree’

It was in early 2024 that the government announced Operation Kagar, intended as the endgame for the Naxalite movement. Focusing on the vast forest areas of the Chhattisgarh, the remaining Maoist heartland, upwards of 60,000 security personnel were deployed as well as advanced drone and surveillance technology. As a result, 2024 was the bloodiest year for Maoist casualties in over a decade, with 344 killed in security operations according to the South Asia Terrorism Portal.

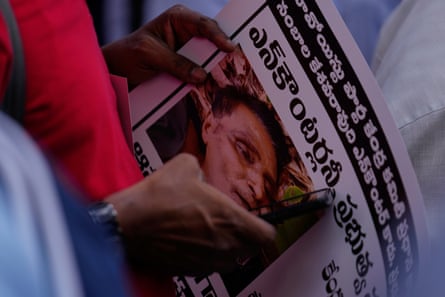

Last month, security officials cornered and killed one of India’s most wanted Maoist leaders, Nambala Keshava Rao – who was almost in his 70s – along with 26 others alleged to be militants. Shah called it a “landmark blow” to the Naxalite movement.

N Venugopal, a newspaper editor who has spent years documenting the movement, claimed that of the roughly 500 people killed since the escalation of the counter-insurgency at the beginning of 2024, around half were non-combatant adivasis, including children.

“This is not an anti-Maoist operation, it is a killing spree,” he said. “Security forces have become like bounty hunters, killing for rewards.”

The claims of atrocities against adivasis in the name of anti-Naxalite operations go back years. Organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have documented over years how security forces have been implicated in extrajudicial killings – including allegations of what is referred to as “encounter killings” in which police stage the deaths of civilians to look like the killing of Maoist fighters – and allegations of arbitrary detention, forced displacement and sexual violence.

Bela Bhatia, a human rights lawyer in Chhattisgarh, alleged that forces in the area had always “enjoyed impunity to carry out abuses and harassment and encounter killings, it’s now just happening on a much bigger scale”.

Bhatia was among several activists and lawyers in Chhattisgarh who said there was a newfound brutality to Operation Kagar, in which the focus was on “neutralising” – meaning shooting to kill – any alleged Naxalite target, with police and paramilitary officers often incentivised with financial bonuses.

“Instead of prioritising arrests, the government has increasingly taken the path of elimination. Civilians are being lumped together with Maoists and killed,” said Malini Subramaniam, a human rights defender and journalist based in Bastar who has faced threats for her work.

Subramaniam said entire adivasis villages in the Bastar area were being rounded up and coerced into surrendering, even if they had no involvement in the Naxalite uprising. “The government has offered only two choices: either surrender or be killed,” she alleged. “When we hear reports of people surrendering, it’s often just ordinary villagers being forced to do so.”

Sundarraj Pattilingam, Inspector Gen IG of Police Bastar Range leading the anti-Maoist operations, called the allegations “completely baseless” and said the operations were all carried out “as per the law”.

He said: “There is no intention to harm any civilians or to harm anyone who comes forward to surrender. The allegations are made up by the Maoists to put a question mark over the action of the security forces and boost up the morale of their cadres, who are already in a very bad shape.”

A war waged ‘for industrialists’

Since the beginning of the year, leaders of the Naxalite movement, which operates as the Communist party of India (Maoist), have put out several statements calling for a ceasefire and expressed willingness to enter into peace negotiations with the government. However, the government has ignored calls for a political or rehabilitation process.

That stance has reinforced a suspicion among activists and lawyers that the primary driver of the recent crackdown was not peace but instead corporate interests. The forests of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand are rich with coal and minerals such as iron ore and some of India’s biggest industrialists have set up mining operations there, with government-approved plans to expand.

Soni Sori, a school teacher turned political leader fighting for adivasis rights in Chhattisgarh, claimed the targeting of adivasis was no accident. The tribal communities have blockaded and disrupted mining attempts in the forests as they fought back against their displacement and the destruction of the forests.

“This is a one-sided war— a war waged by the government against the people of this region, all to clear the way for industrialists desperate to seize the area’s mineral wealth,” said Sori.

The home ministry did not respond to request for comment. A home affairs statement in April said the government focused on “security, development, and rights-based empowerment” in areas affected by the Naxal insurgency and said that “the vision of a left wing extremism-free India is closer than ever”.

Prakash Singh, the former commander of India’s Border Security Force and author of a book on Naxalites, said he believed organisationally the Naxalites would ultimately be crushed and he called for a more “humane” approach.

“Give them the opportunity to come out from the underground, lay down their arms and be given steps for rehabilitation,” he said. “This way the government would achieve the same objective, without all this bloodshed.”

Yet he also acknowledged that it was much harder to destroy the beliefs that have driven the insurgency. “You can kill the cadre, you can liquidate the party,” said Singh. “But as long as there is injustice, as long as there is exploitation or the displacement of the poor in any part of the country, the Naxal ideology is going to survive.”

3 months ago

44

3 months ago

44