Heatwaves on the rise

Around the world, global heating is already giving us more frequent heatwaves, and when we get them they are lasting longer and bringing more heat.

As burning fossil fuels adds more and more heat to the planet, climate scientists know these trends will get ever more deadly.

According to the medical journal the Lancet, heat extremes caused an estimated 546,000 deaths every year between 2012 and 2021 – a 63% rise on rates seen in the 1990s.

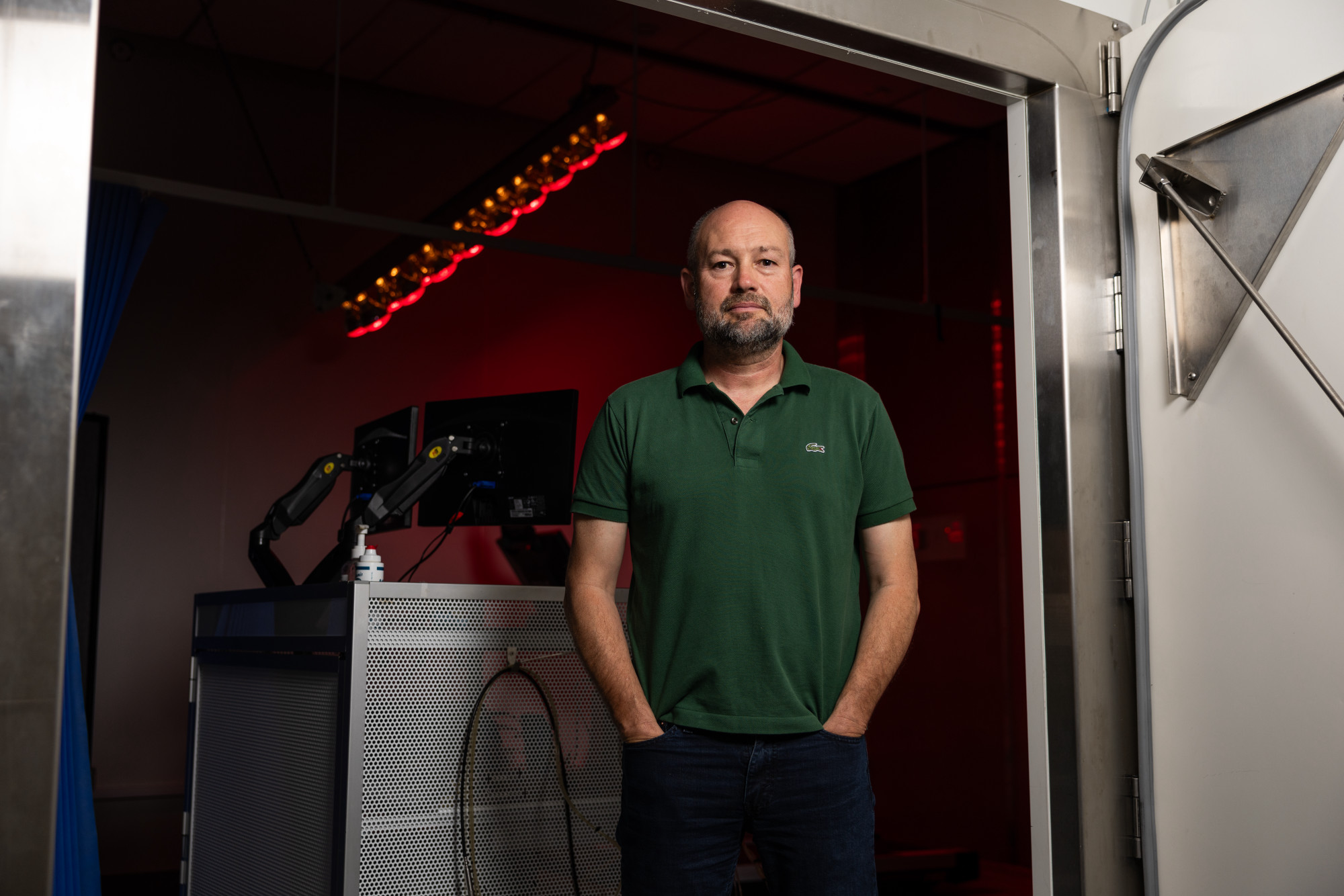

“That's the equivalent of a fully loaded jumbo jet full of people going down once every seven hours throughout the year,” says Prof Ollie Jay.

“And the really important thing to keep in mind is that every heat related death is preventable.”

Jay is the director of the Heat and Health Research Centre at the University of Sydney, the home of the Thermal Ergonomics Laboratory – a chamber the size of a big bedroom where the temperature and humidity can be tightly controlled.

So what does extreme heat do to the body? What does it feel like to take a walk in the kind of heat that will become all too frequent in the very near future?

Me and my 51-year-old body are here to find out. I'm going to go into the climate room twice. The first time, it's going to be 43C and 18% humidity – the sort of conditions we'll see a lot more of in place like Sydney, Mexico City and São Paulo when global warming gets to 2C. That might only be a couple of decades away.

What heat does to your body

After the first experiment, Jay explains to me what I just went through.

"So whenever people think about hot weather, they always talk about the temperature," he says.

"There's two issues with that. First of all, most people don't realise that the temperature is measured in the shade.

"So if you're in direct solar radiation, the amount of heat stress you're exposed to is much greater as it will stress your body out a lot more."

That explains the heat lamps. And, according to Jay, the other important variable is the humidity.

"Humidity is the amount of water vapour that's in the air. And the reason that's important is that the only way in which your body can physiologically keep cool is that you produce sweat.

"But it's not production of sweat that cools you down. It's the evaporation of sweat and it's the humidity in the air that prevents that sweat from evaporating, even though the ambient temperature might be the same."

So when high humidity goes along with extreme temperatures, your body can no longer cool itself down, and the heat becomes deadly.

This is why in the next experiment I'm going to experience conditions at the same temperature as the first experiment, but with a much higher humidity of 36%.

Even though 36% relative humidity doesn't sound high, at 43C that means a lot of moisture because warmer air can hold more water. When it's this hot, sweating isn't going to help me stay cool very much.

Another way to think about it is the "feels like" temperature that weather forecasts sometimes tell us about. Under the conditions I am experiencing, the "feels like" temperature is over 49C or 120F.

An avoidable future?

So the extreme heat forced my heart to work overtime, I lost weight, and while I wasn’t really conscious of it, my core temperature went up.

If you were stuck in these conditions they could be deadly. My body had no way to compensate for the heat and cool itself down.

But as Jay says, the impact of heatwaves isn't just about how deadly they are.

"It's also about the way in which heat affects people's ability to carry out their daily activities," he says.

"It's a real problem for people in the workplace, particularly if you can't extract yourself from those extreme heat conditions.

"It impacts our ability to be productive and safe in the workplace as well."

Extreme heat can have all sorts of effects – it has been linked to an increase in the risk of still births and low birth weight and it puts infants, the elderly and people with underlying problems such as heart or kidney disease at increased risk.

“So there's all these different types of impacts that extreme heat can have on human health and wellbeing, but are not necessarily just in that mortality statistic,” Jay says.

And we know that global heating is only going to make these sorts of heatwaves – and all of the direct risks to humans – more common.

"It is very plausible that those impacts are just going to escalate. In fact it's pretty much almost certain, unless we unless we figure out a way to mitigate climate change in a more effective way.”

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1