It was a dreary Monday morning in September 2016, and I was working as a teacher, trying to settle a new year 7 class, when a sharp pain bloomed behind my right eye. It was followed by quick jolts, like electric shocks. As each class came and went, the pain eased and then returned with greater intensity. Four times that day I left a teaching assistant with worksheets and ran to the school bathroom to douse my face with cold water. I took ibuprofen, paracetamol, aspirin, but the pain remained unbearable.

The headaches appeared repeatedly that autumn, and again in spring, and soon formed an annual pattern. September and October were the worst, then February and March. I could predict the routine: aura in the shower, early twinges on the train, full-blown agony in class by 9.30am. In late 2019, a GP finally referred me to a neurologist and I was diagnosed with cluster headaches.

About one in 1,000 people are affected by the condition, and men are more frequently diagnosed. Cluster headaches typically begin with sudden, severe pain around one eye that peaks within minutes and lasts up to three hours. Attacks come in clusters, daily or multiple times a day, and are accompanied by red or watery eyes, drooping eyelids or facial sweating. I have the episodic form, which arrives in seasonal bouts; others have chronic cluster headaches, defined by the absence of long pain-free periods.

What unites sufferers is the intensity. One study rated the pain at 9.7 out of 10, higher than bone fractures or pancreatitis. Another found 64% of cluster headache patients experienced suicidal thoughts during bouts; the number dropped to 4% when they were not in pain.

Val Hobbs, 74, a chronic sufferer from Pembrokeshire, isn’t surprised. Her attacks began when she was two. “I would throw myself on the floor and bang my head. That was put down to being spoiled,” she says. Her symptoms worsened through childhood. Alcohol in her teens, like many triggers, made things worse. After drinking sherry at her school leaving party, she recalls barely being able to see on the bus home.

Her family often interpreted her attacks as drunken episodes. Support eventually came from her father and then from her husband, Rod, who was diagnosed with epilepsy in early adulthood. “I was very lucky to find such an exceptional person,” she says. “We were meant to meet.” Hobbs took clerical work after moving to Wales in 1981, but often hid her condition. She was fired from one job, partly due to absences during attacks. Her breakthrough diagnosis came in 2002 at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London.

Still, the inability to plan life around unpredictable attacks took its toll. She especially hated being unable to plan social events, being seen as unreliable as a colleague, and even having to be looked after by her children (at home and in public) in the midst of the paralysis caused by the worst episodes. “It robs you of the small freedoms we don’t appreciate until they’re gone,” she says. She remembers winning tickets for the queen’s golden jubilee concert, only to have an attack inside a portable toilet.

Headaches have been described throughout history. “The first description of headache comes by way of the Mesopotamians in 4000BC,” write Seymour Diamond and Mary Franklin in their 2005 book, Headache Through the Ages. They attributed the disease to Tiu, an evil spirit who attacked his victims’ heads.

The Ebers Papyrus, a record of ancient Egyptian medical knowledge dating from 1550BC, suggests crocodiles should be wrapped around the head to combat what some modern-day observers would describe as a migraine. In the middle ages, migraine was recognised as a distinct disorder, with treatments ranging from bloodletting and herbal concoctions to other, more superstitious remedies.

It was the Dutch physician Nicolaes Tulp who provided the first detailed description of a cluster headache. In his Observationes Medicae, published in 1641, Tulp speaks of a patient “afflicted with a very severe headache occurring and disappearing daily at fixed hours”.

Cluster headaches were only officially recognised by the Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society in 1988. From the 1960s to the late 1990s, they were thought to be caused by a problem with the carotid artery, which supplies blood to the brain, says Prof Peter Goadsby, a leading specialist in diagnosing and treating the condition.

In 1998, Goadsby and the neuroscientist Arne May published the results of a study for which they had triggered cluster headaches in patients and monitored the attacks in a brain scanner. The results, published in the Lancet, showed activation of the hypothalamus, which is responsible for human circadian rhythm, when patients were in pain, and a deactivation when they recovered.

Despite such advances, diagnosis remains slow. Jamie Charteris’s attacks began in 1986 and felt like “a modelling balloon being inflated behind my left eye”. GPs thought he had sinus problems; he underwent four surgeries before finally being diagnosed in 2014, after a doctor Googled his symptoms.

Dr Nicholas Silver, a neurologist at the Walton Centre in Liverpool, says delays in diagnosis and treatment happen because patients are rarely seen mid-attack. “You’re tired and depressed, but not in agony,” he says. He proceeds by ruling out other primary headache disorders, such as migraine, tension-type, hemicrania continua, paroxysmal hemicrania and SUNCT (short-lasting unilateral neuralgiformheadache), before diagnosing cluster headaches. A detailed history is essential: on which side do symptoms appear? For how long? What time of year? Are there triggers, such as alcohol? Do symptoms change with touch? Certain features such as redness, tearing, drooping eyelids and nasal congestion help confirm cluster headaches. Once diagnosed, patients may be referred to specialist centres including the Walton, or rapid-access clinics such as the one I attend at St Thomas’ hospital in London. But many first arrive in A&E or are given inadequate treatments.

Dorothy Chapman, 78, is a trustee of the UK charity Ouch (Organisation for the Understanding of Cluster Headache). She has experienced cluster headaches for most of her life, although she hasn’t had an attack since 2016. When she was in her 20s, she had her teeth pulled because dentists misinterpreted her pain. She believes dentists still need much more awareness. When Charteris sought help from Ouch, it was Chapman who replied to his email. I remember calling the Ouch helpline during an attack in early 2021; a calm volunteer talked me through oxygen treatment and medication until the episode eased.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) guidance on treatment recommends sufferers are offered high-flow oxygen and/or the anti-migraine drug triptan delivered by injection or nasal spray. No tablets, painkillers or opioids should be used. Preventive options include verapamil, a blood pressure medication, which apparently soothes Harry Potter actor Daniel Radcliffe’s bouts.

But Dr Giorgio Lambru, the consultant neurologist who diagnosed me, believes the Nice guidance needs updating to reflect a clearer treatment pathway and help GPs avoid misprescribing. For episodic patients, he says, timing is everything: “The duration of the bout dictates the treatment.” Short bouts with infrequent attacks are handled with abortive therapy alone: triptan injections or nasal sprays, plus oxygen. Longer or more intense bouts require preventives such as verapamil, sometimes paired with steroids, which act quickly before wearing off. Many patients also receive a greater occipital nerve block during a bout – an injection into the side of the head where the pain is that reduces nerve activity.

If these fail, Lambru may consider topiramate, an anti-epilepsy medication, or vagus nerve stimulation devices. Chronic patients sometimes require multiple nerve blocks, radio-frequency treatment or, in rare cases, neuromodulation through occipital nerve stimulation, in which a battery-operated device is implanted and zaps the nerve to calm it down. Lambru stresses that, unlike in migraines, frequent use of triptans to treat cluster headache rarely causes medication-overuse headaches – an important point missing from many GP guidelines.

Patients also experiment with other approaches: cold air, cold showers, intense exercise, caffeine, vitamin D and in some cases psychedelics, though evidence remains largely anecdotal, according to Lambru. One promising emerging option is CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) targeting medication, used in migraine. Injectables such as galcanezumab, which aim to slow the potent inflammatory protein, show potential for episodic cluster headache treatment but are unavailable on the NHS.

My own treatment journey has involved preventives and acute options when bouts strike. I briefly tried verapamil, but Covid restrictions made the required ECG monitoring (because of risks to the conduction of the heart) difficult. Oral steroids helped me temporarily but couldn’t be used long-term because of the increased risk of harm, such as weakened bones, eyesight problems and diabetes. Greater occipital nerve blocks became my main preventive tool. The moment I sense patterns emerging, I call the headache clinic at St Thomas’, and the nurses fit me in as soon as possible.

When attacks hit, I use high-flow medical oxygen delivered to my home in tall industrial cylinders. The relief is extraordinary. Prof Goadsby and Dr Anna Cohen’s 2009 study showed oxygen could make patients pain-free within 15 minutes, leading to its approval by Nice. During a cluster attack, blood flow in the brain increases. Oxygen therapy constricts the dilated blood vessels, reducing the pressure and pain while calming down overactive nerves. The drug sumatriptan, which reduces the release of pain-causing chemicals and blocks pain signals from being transmitted to the brain, never worked for me, despite trying several forms.

Hobbs also relies heavily on oxygen, though she believes demand-valve masks, which deliver big bursts of oxygen quickly, could improve outcomes. Ouch has campaigned for wider access to these masks, though Lambru notes evidence is still emerging. The challenge is that only about one in 10 UK patients use or have access to oxygen – a stark shortfall, considering its effectiveness.

At Ouch’s annual conference in Newcastle last summer, about 100 sufferers gathered with neurologists. There were quiet rooms, oxygen stations and sessions on new research and coping strategies. A recurring theme was the need for better data. Headache diaries help clinicians recognise patterns, but until recently most were kept by hand.

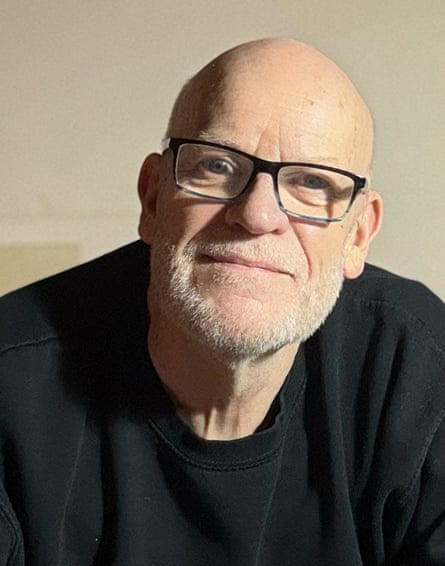

Inspired by his own struggles, 37-year-old web developer Darshan Ramanagoudra created MyClusters, a free app for tracking attacks, triggers and treatment effectiveness. Within its first month, users from more than a dozen countries logged thousands of attacks. Ramanagoudra hopes better data will reduce misdiagnosis and strengthen research.

“By the summer of 2023, I was getting multiple daily attacks. By the winter, it was about six a day, and that’s when I started reading a lot of medical papers,” says Ramanagoudra, who is based in the Netherlands. He consulted doctors and researchers to see what the online community in the Netherlands was saying, then started tracking it all on a spreadsheet. “It got a bit complicated, and I realised I could do pivot tables and things, but I figured someone else would want additional information. How were they going to do it?” The idea for MyClusters was born.

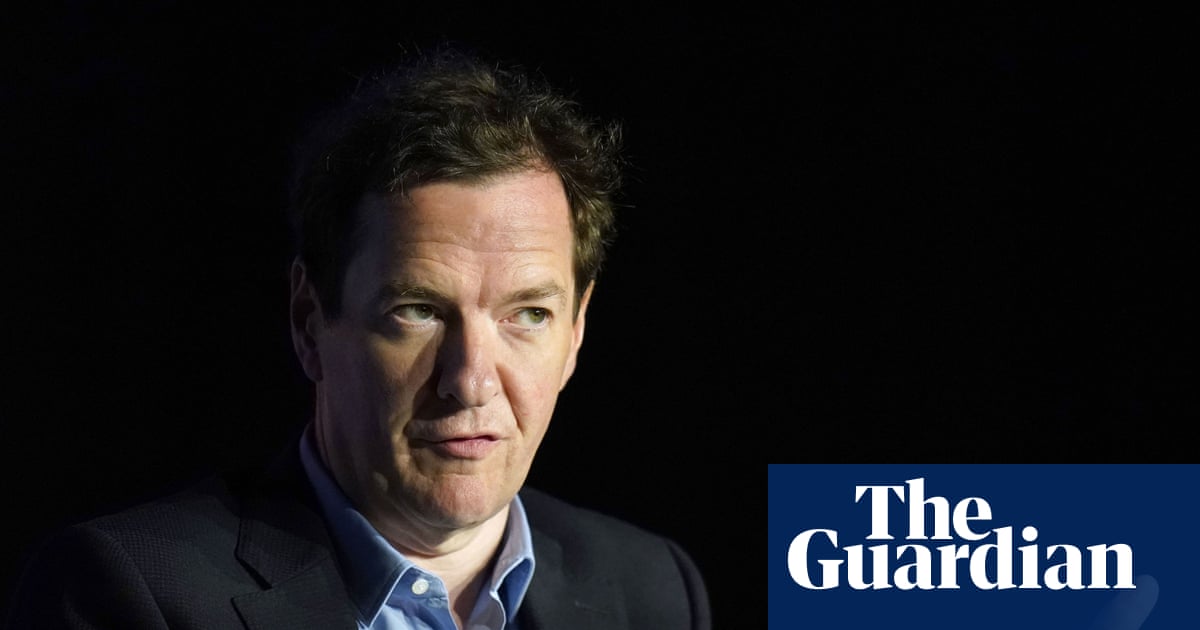

The percentage of cluster headache sufferers, diagnosed or undiagnosed, in each country is estimated to be about 6.5%, says Tom Zeller Jr, the author of the 2025 book The Headache: The Science of a Most Confounding Condition – and a Search for Relief. However, in terms of funding and research, “cluster headaches are given short shrift compared with the impact it has on our economies and on people’s individual lives”, he says. He believes this is a mistake. “It’s not a terminal disease, it’s a lifelong disease. But if you add up all the time a person spends being disabled by these bouts of head pain and other neurological symptoms, it adds up to a lot.”

I’ve just emerged from my latest autumn bout. This time the pain struck on the left side, a first for me, and I received my first multi-cranial block to treat it. I was injected four times in the side of my head, plus another shot at the back. I’m not needle-phobic; I imagine I’m giving blood from my skull. The approach seems to have worked. Using MyClusters to track patterns, I’ve been headache-free for nearly six weeks.

Winter brings respite, and is a time of calm. But sometime in this new year, I know the cycle will begin again. Cluster headaches are my own recurring, disabling season, never too far around the corner.

1 month ago

34

1 month ago

34