I’ve noticed an interesting micro-trend emerging in the last few years: millennial nostalgia games. Not just ones that adopt the aesthetic of Y2K gaming – think Crow Country or Fear the Spotlight’s deliberately retro PS1-style fuzzy polygons – but semi-autobiographical games specifically about the millennial experience. I’ve played three in the past year. Despelote is set in 2002 in Ecuador and is played through the eyes of a football-obsessed eight-year-old. The award-winning Consume Me is about being a teen girl battling disordered eating in the 00s. And this week I played a point-and-click adventure game about being a college student in the early 2000s.

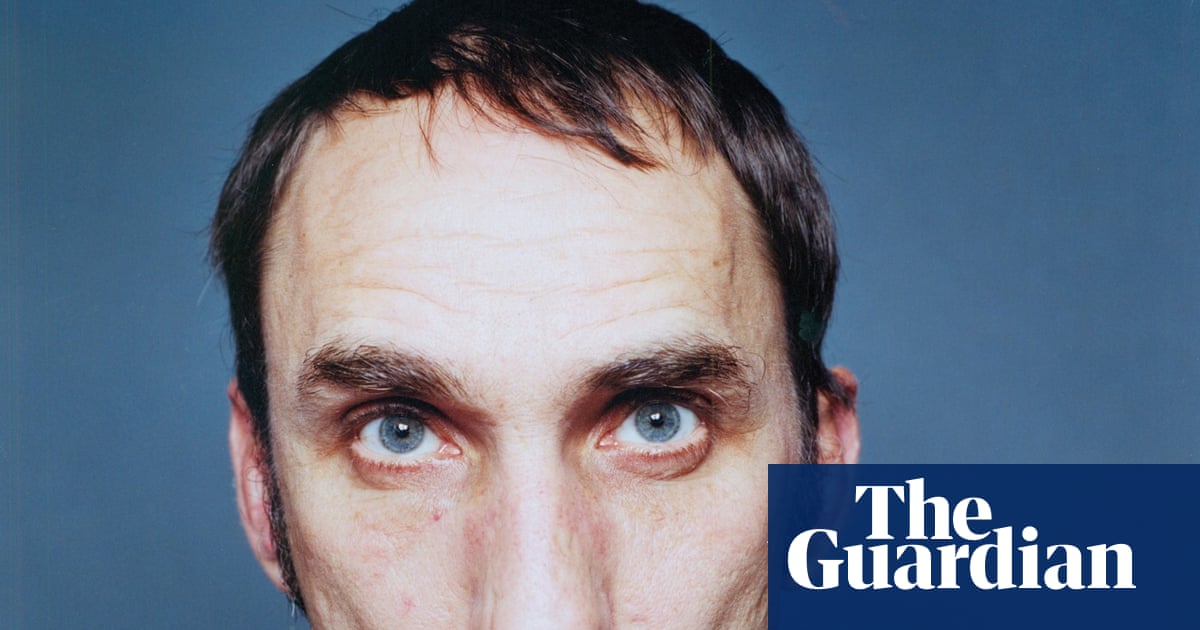

Perfect Tides: Station to Station is set in New York in 2003 – a year that is the epitome of nostalgia for the micro-generation that grew up without the internet but came of age online. It was before Facebook, before the smartphone, but firmly during the era of late-night forum browsing and instant-messenger conversations. The internet wasn’t yet a vector for mass communication, but it could still bring you together with other people who loved the things that you loved, people who read the same hipster blogs and liked the same bands. The protagonist, Mara, is a student and young writer who works in her college library.

The earnestness with which Perfect Tides presents the college experience – quoting full paragraphs from pretentious texts, awkward interactions with classmates, stilted phone calls with Mara’s boyfriend back home – predates the concept of cringe. A key difference between the millennial generation and that of gen Z is that millennials did not grow up curating an online image on social media, and therefore had a much lesser terror of being perceived. We’d put up entire albums of terrible, blurry photos from a single night out, write nonstop on LiveJournal, produce appalling juvenilia and then post it on fanfic or art forums.

Naturally, we find this embarrassing now, as do the younger generation, who enjoy making fun of millennial cringe. But Perfect Tides takes place in a time where nobody was worried about being embarrassing online or, indeed, in person. It’s a time before “hipster” emerged as an insult. Mara inhales everything around her – an anarchist philosophy book, music and movies, everything she hears professors say in class, new relationships – and reading, talking to other characters, and writing essays deepens her understanding of these topics, opening up new avenues of conversation in turn. It’s a cute way of gamifying the process of expanding your intellectual and taste horizons. She’s at an age where every experience and idea is new.

Perfect Tides shares an aesthetic with Consume Me. Each embrace the sometimes messy pixel-art of 90s computer adventure games – but Consume Me’s tone is comedic and satirical where Perfect Tides’ is earnest. Both, however, are part of a long tradition of coming-of-age stories that emerge from every generation that has had the luxury of education and a free-form young adulthood. “Emerging adulthood”, a phrase coined by psychologist Jeffrey Arnett in 2000, is a useful descriptor for this stage of life: the extended period of identity formation, distinct from adolescence, that usually happens between 18 and 29 in societies where it is economically possible and culturally permissible for young adults to pursue further education.

For a lot of people, this is an especially redolent and memorable period of life, which is why there are so very many novels, films and TV shows about young adulthood. Playing Perfect Tides reminded me of Douglas Coupland’s youth-memoir novel, Generation X, which was part of the cultural canon when I was a teenager. And it makes sense that the first generation to truly grow up with games – my generation – is now making sense of those experiences through creating games. The bildungsroman of the 1800s has become the autobiographical indie game of the 2020s.

It is the very specificity of Perfect Tides – the year, the setting, Mara herself – that makes it feel so human and personal. You don’t have to be part of a specific generation to appreciate that generation’s art: when I read autofiction set in the 1960s or the 80s, I learn something about what it felt like to be alive in that time. When I play these millennial autofiction games, I relate to them more closely – there are aspects of Mara’s young-adulthood experience that closely mirror my own – but I’m still learning something. By spending a little time in these fictionalised memories, I’m learning how someone else experienced those same formative years.

What to play

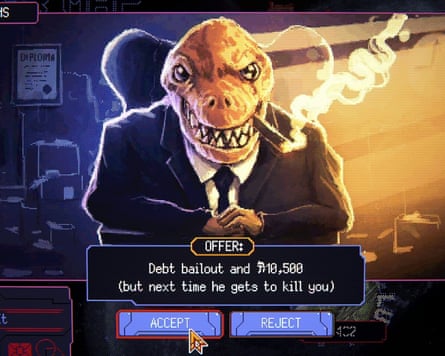

Look, I just can’t face another capitalist-dystopia piece of media at the moment. So I’m going to have to save Space Warlord Baby Trading Simulator for a little later in the year, when I’m feeling more resilient. In this strategy-game-meets-stock-market simulator, you bet your credits on the life outcomes of fictional alien babies, watching their lives play out in text alerts. This anticapitalist satirical offering is from the people at Strange Scaffold, a studio that has now made a profitable habit of turning tweet-length jokes into full games (see also Creepy Redneck Dinosaur Mansion and An Airport for Aliens Run By Dogs).

Available on: PC

Estimated playtime: 1-3 hours

What to read

-

Sony has patented the idea of personalised AI podcasts hosted by characters from its games. I am equal parts horrified and darkly amused by the thought of PaRappa the Rapper reading out patch notes.

-

UK game retailer GAME has died yet another death, reports the Game Business, having struggled since the early 2010s. Its last three shops will close, and most of its other operations have already wound down. It will continue to exist within Sports Direct and House of Fraser stores.

-

I’m still not done thinking about Hollow Knight Silksong, so I enjoyed this article by Nicole Clark, on the new feminist games website Mothership, about the game’s unexpected compassion.

-

Bloomberg visited Obsidian – one of Microsoft’s most interesting developers – for this studio profile, in which its leaders talk about how they ended up releasing three games in 2025.

-

And finally: my book about Nintendo is finally out this week in the US, and next week in the UK. I’m doing a bunch of launch events in Glasgow, Edinburgh, St Andrews, London and Brighton. I’d love to see you there – tickets are here.

What to click

-

There’s a reason that Wii Bowling remains my mum’s favourite game of all time | Dominik Diamond

-

Cairn – obsession, suffering and awe in a climbing game that hits exhausting new heights | ★★★★☆

-

Iron Lung – YouTuber Markiplier crash lands with big-screen sci-fi horror | ★★☆☆☆

Question Block

This week’s question comes from reader Gavin:

“Could you explain the current debate around physical game ownership v digital? And the grey area of buying a digital code in a physical box? I can’t imagine those codes will be collector’s items in 10 years’ time ...”

Once upon a time, all video games came on cassette tapes, discs or cartridges, usually in tragically damage-prone cardboard boxes, with paper manuals. Then, when digital downloads became practical, we had a choice: either you buy your game on a disc in a box, or you go for the convenience of a downloaded version that exists on your hard drive. Now, however, it is difficult or even impossible to buy many games in a physical format. And even when you do, the disc simply prompts a 50GB download, or the box contains nothing but a redeemable code.

Digital downloads are preferable for the businesses that run the gaming industry, for two reasons. Firstly: there are no manufacturing, packaging and shipping costs. Secondly: Sony, Apple, Steam, Microsoft or Nintendo gets around a 30% cut of every game sold digitally on their platforms, which is essentially free money for them. At one point, game retailers had too much power for these platform holders to abandon physical games: too many copies of FIFA and COD were sold at branches of GAME. But now, with bricks-and-mortar game retail a vanishing business, digital downloads are the norm.

Digital downloads are convenient for players, of course, but they also come with huge disadvantages. What you’re buying is a licence, which at some theoretical future point could expire or become unusable, rendering your games unplayable. You can’t sell on a digital code or transfer ownership. For this reason a lot of people still prefer physical media, of all kinds. And everybody hates code-in-a-box. It’s the worst of both worlds.

If you’ve got a question for Question Block – or anything else to say about the newsletter – email us on [email protected].

3 weeks ago

28

3 weeks ago

28