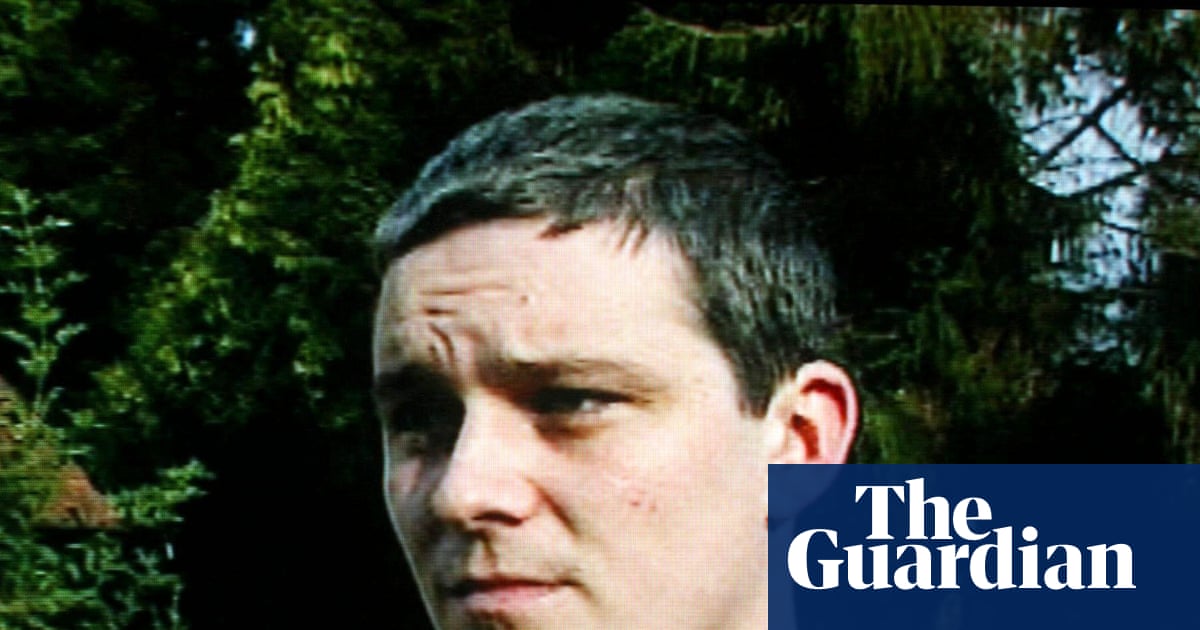

The most dramatic moment in the deposition came when Roderick Gadson, an Alabama prison guard, was questioned under oath about an incident in which he and other officers used such devastating force against a prisoner that the man had to be airlifted to hospital to treat his injuries.

Gadson was shown a photograph of the man, Steven Davis. He was lying in an ICU bed breathing through a tube, his cadaverous face bruised and covered with blood, his eyes black and sunken.

Gadson was asked whether he felt that the amount of force used had been appropriate, given the way Davis looked.

He replied: “I don’t feel like nothing. I just did my job.”

On 4 October 2019, Gadson and five other officers were called to respond to a security breach inside Donaldson correctional facility. Davis, 35, had attempted to attack another prisoner using a couple of improvised plastic knives.

According to correctional authorities, Davis refused to comply with the officers’ orders even after they had sprayed him with Mace, and they had no choice but to restrain him using justifiable force.

Several prisoners who witnessed the encounter up close told a different story. They said that even after Davis had put down the makeshift weapons and was lying prone and unresistant on the ground, Gadson took the lead.

One of the witnesses said the officer hit Davis “with his metal stick in the head, picked him up, throwed him down. He stomped the dude with his size 15 boot. The guy’s head bounced like a basketball.”

Davis was flown by helicopter to the hospital. As a US Department of Justice investigation found, the prisoner had sustained serious injuries as a result of the officers’ actions, including fractures to his skull, eye sockets, left ear and cheekbone, and to the base of his skull.

A medical examination identified 16 distinct injuries to his head and neck. Some of the blows caused internal bleeding on the brain.

David died the following day. The cause of death was officially recorded as homicide caused by “blunt force injuries of head sustained in an assault”.

Despite evidence of a physical assault by Gadson and the other officers, they were all cleared after an internal investigation.

Six months later, Gadson was promoted from the rank of common correctional officer to sergeant.

Then, in July 2021, he received a letter from the governor of Alabama and the head of the state’s department of corrections. “Congratulations on your promotion,” the letter enthused. “We are confident you will satisfactorily complete the probationary period and give a long valuable service.”

Gadson had been promoted a second time, 21 months after a prisoner in his care had been beaten to death.

Now he held the exalted status of lieutenant.

The beating death – and what it reveals about Alabama’s prisons – has been brought slamming into the public consciousness by a new HBO documentary, The Alabama Solution. Film-makers Andrew Jarecki and Charlotte Kaufman have exposed harrowing brutality within the prison walls, largely basing their work on footage captured by the incarcerated on contraband cell phones.

Since its release in October the film has roiled Alabama politics, with a movement growing among lawmakers, prisoners’ families, and advocacy groups demanding answers. One of the questions they are posing relates to Gadson.

How is it possible, their inquiry goes, that the Alabama department of corrections (ADOC) continues to employ an officer alleged by numerous eyewitnesses to have wielded deadly force against a compliant prisoner?

Public records show Gadson’s history of force goes far beyond Davis’s death. He has been named as a defendant in at least 26 “pro se” lawsuits – legal actions brought in federal court by individual prisoners representing themselves, all of whom alleged they were subjected to excessive force at Gadson’s hands.

Of those 26 cases, some have been settled with a financial payment being made to the prisoner or their family. Other cases have hit technical hurdles which prevented them from advancing to trial, while in six cases the court found in favor of the defendants.

Chris England, a Democratic state lawmaker representing Tuscaloosa, is one of those now calling for Gadson to be fired. “He is a symbol of what’s wrong with our department of corrections,” the representative told the Guardian.

“You have a culture within the system that not only enables abusers, but encourages them by not holding them accountable. We need a deterrent, to show the rest of the world that we are no longer going to tolerate that sort of violence.”

Jarecki puts the accountability argument even more strongly: “Gadson’s record of lawsuits and settlements, and his killing of Steven Davis, indicate that he is one of the most violent prison guards in America,” he said.

“Yet the Alabama department of corrections continues to employ him. He’s not getting fired, he’s not getting sidelined, he’s getting promoted.”

Most prisoners in Donaldson correctional facility called Gadson “Big G”. It was a nod to his physical frame, which as he disclosed during the deposition he gave for one of the 26 civil lawsuits was 6ft3in and almost 300lbs.

The son of a retired police officer and a real estate manager from Birmingham, Alabama, he joined the prison service in 2007 and has been employed by it ever since. In the deposition, Gadson was asked why he had wanted to be a corrections officer in the first place.

He replied: “Because it’s steady”.

Over the years he has worked at several of Alabama’s 13 prisons, including some of their roughest units.

That includes the segregation wing known as the “behavior modification unit”, or “hot bay”, in Donaldson prison where Gadson has spent much of his career. This is where the most troubled and violent prisoners are held, and where the deadly Davis beating occurred.

That is also where several of the 25 other acts of alleged abuse levelled against Gadson took place. The first excessive force lawsuit in which he was named related to an incident in March 2008, just a year into his prison service.

A prisoner, Kenneth Knabenshue, alleged that two officers had threatened to “annihilate” him after he got into a verbal argument with them. The prisoner started a fire in his cell, saying it was to protect himself against their attack, and the Cert team was summoned.

The “correctional emergency response team”, Cert for short, is legendary inside Alabama prisons. The prison authorities revere it, hailing it as a highly trained group of specialist officers who can handle even the most volatile situation.

For the prisoners, however, the Cert team has a different connotation. They call it the “wrecking crew”, and fear it as a coterie of the biggest, meanest officers renowned for their aggression.

Quante Cockrell, who worked as a prison officer alongside Gadson at Donaldson correctional facility from 2012 to 2019, told the Guardian that the Cert team regularly engaged in beatings. “Cert team members, they just had open range. They’re encouraged to be more and more aggressive, and when an inmate refuse an order, they gonna beat his ass.”

Knabenshue alleged in his lawsuit that though he made clear he would not resist the Cert team, they pulled him out of his cell and proceeded to beat him. He accused the officers, including Gadson, of “stomping, kicking, punching, slapping, and hitting me with a stick and shield”.

He then alleged he was thrown down a flight of stairs and stomped on the head again “by an officer who weighs over 300lbs”. He was dragged to the prison infirmary to have his injuries treated, where the prisoner alleged he was beaten some more in front of medical staff.

Alabama asked for the case to be dismissed, arguing that the prisoner had been aggressive and non-compliant and that Gadson and the other officers involved had not violated any of his constitutional rights. The judge denied the state’s request, and the case was settled.

The deposition in which Gadson was quizzed about his work as a prison guard related to an incident on 15 April 2019 in which another prisoner, Demarcus Coleman, alleged he was randomly picked upon and beaten by Gadson and two other officers.

Coleman’s lawyer asked Gadson during the sworn testimony how many times he had used force.

“I’ve had plenty, but I can’t give you a number,” Gadson said. “I ain’t fixing to tell you that I ain’t never used force because I’d be lying to you. I ain’t never used excessive force.”

Asked under what circumstances it was appropriate to use force, Gadson replied: “When it’s necessary”.

Pressed by the lawyer, he went on to say: “I’m not going to be afraid to do my job. I mean, you’re not just going around using force on inmates for nothing, but if an incident warrants force, I won’t be scared to use it.”

Alabama has been dubbed America’s ground zero for prison brutality. A database compiled by The Alabama Solution producers records that 1,377 people died in the state’s prisons in the five years to 2024 – many from drugs, homicide or suicide, and fewer than half from natural causes.

Almost half of the prisoners who died, 660, were Black. That is wildly disproportionate in a state whose population is about a quarter African American.

In a similar five-year period, the state settled more than 100 civil rights lawsuits, 94 alleging excessive force. The bill for defending the accused officers, and for settling their cases, reached an astronomical $17m.

The commissioner of the ADOC, John Hamm, who has led the prison system for the past three years, has admitted there is a problem. In October, he was quizzed at a public meeting by England, the Tuscaloosa lawmaker, who pointed specifically to Gadson as being symptomatic of a culture of abuse.

Hamm replied: “The culture that you mention, it’s there, and that’s something we’ve been working on for quite some time. But it’s tough.”

The Guardian offered the ADOC the opportunity to respond to detailed questions on Gadson’s track record and the wider problem of excessive force in its prisons, but received no reply.

The US justice department’s 2020 investigation into Alabama prisons concluded that “correctional officers frequently use excessive force on prisoners” often resulting in “serious injuries and, sometimes, death”.

The investigators found that a pattern of abuse was exacerbated by extreme overcrowding within the prisons, combined with severe understaffing. Gadson talked about those problems in his deposition, saying that staff were “horribly outnumbered” by prisoners.

To mitigate understaffing, he said, he was obliged to do so much overtime that he often exceeded 60 hours of work a week.

Conditions inside the facilities are brutal for prisoners and staff alike, testing even the best intentions of recruits. “Many officers go in wanting to make a difference, but they soon discover that they can’t,” said Erika Marsh, a mental health counselor who worked at Donaldson correctional facility from 2018 to 2021.

“They’re working around the clock, exposed to inmates who are on drugs or who can become violent, severely mentally ill men who are not on medications or getting treatment. The culture of it all tears people down.”

Shervanae Scott worked as a prison social worker for three years inside St Clair correctional facility, where Gadson was transferred after the beating death of Davis. Her job specifically focused on rehabilitation of prisoners and their re-entry into society.

“Yeah, but it never happened,” she told the Guardian.

Scott was so traumatized by her experiences inside St Clair that she believes she has been permanently scarred. “It was like I was incarcerated myself. I felt defeated, suicidal,” she said.

Her office was in the restricted housing wing where prisoners were locked up in isolation. “I would see them pulling inmates out of their cells and beating them on the ground,” she said.

Whenever she witnessed officers beating inmates she always reported it up to senior leadership. For her pains, she was accused by fellow staff of being an “inmate lover”, and her rehabilitation work with prisoners was stymied.

By the time she left the service she had reached the conclusion that the “system doesn’t care. It was set up to defeat us.”

None of the 26 lawsuits brought by inmates against Gadson has led to a prosecution or documented disciplinary action. The ADOC has never admitted wrongdoing.

But the complaints have cost Alabama taxpayers a pretty penny. The film-makers of The Alabama Solution have used freedom of information laws to extract data from the state that shows that almost half a million dollars have been spent in settlements with prisoners or their families before the suits get to trial.

In total, 10 legal actions brought by inmates naming Gadson have been settled, costing Alabama the grand total of $426,350. The film-makers also found that a further $2.5m was approved by the state to defend against litigation in cases involving Gadson.

Sixteen of the cases brought against Gadson and other officers did not reach a settlement. Of those lawsuits, five were thrown out by a judge finding on behalf of Gadson and the other officers, and in one a jury returned a verdict also finding for them.

Nine of the cases hit technical glitches which prevented them from proceeding. In those legal actions, judges did grant the prisoners permission to come back with a refined suit. One case remains open.

Such is the absence of repercussions for officers accused of abusive behavior in Alabama that in his deposition Gadson appeared to be largely unaware of the number of cases brought against him and of their cost to his employers. He has never had to pay a dime out of his own pocket.

The 26 lawsuits naming Gadson are spread out over a 15-year period, from the Knabenshue case that went to court in 2009 to 2024 when the Davis suit was settled.

Most of the lawsuits are handwritten by prisoners in ballpoint pen, replete with spelling errors and quirks of grammar but all making the same allegation that Gadson and other officers brutally and gratuitously beat them.

Prisoner William Harris alleged that on 4 May 2010 Gadson and another officer handcuffed him, then pepper sprayed him in the face before beating him with a night stick until he passed out. “They beat me viciously, as if I were a plastic punching bag instead of a human being,” the lawsuit claimed.

In an affidavit, Gadson denied having mistreated Harris and alleged the prisoner was aggressive and had been carrying an improvised knife. The case settled with the state paying Harris $30,000 without admitting liability.

On 12 April 2017, Gadson was involved in two separate events at Donaldson prison. Both prompted federal lawsuits.

Prisoner Terry Carstarphen alleged in his complaint that he was Maced in the face by a separate officer and then Gadson “began striking me in the head with a metal baton, busting my head in the process”. That case ground to a halt after the prisoner was unable to pay a $17 filing fee.

Fellow prisoner Zackery Wilson alleged in a separate lawsuit that on the exact same day he was “maliciously assaulted while inside my cell not causing any type of disturbance”. He named Gadson as one of the officers who he alleged punched him repeatedly in the face, then stamped on him on the ground leading to a contusion at his left eye and a “permanent knot to the left side of my head”.

Amid the repeated pattern of alleged assaults, some details stand out as especially disturbing. Thadous Dinkins claimed in a court document that on 12 June 2018 he handed over a razor to Gadson and told him he was suicidal; instead of seeking mental health support, Gadson and two other officers allegedly beat the prisoner with slaps and punches.

As the 26 lawsuits progress, the scale of settlement payments has grown exponentially. The first settlement, with prisoner Knabenshue in 2008, was for a mere $350.

But then the big money kicked in: $30,000 in the case of Harris in 2010, followed by a $40,000 settlement in 2017. All in all, 10 lawsuits ended with financial payouts from the state.

After Davis died, his mother, Sondra Ray, sued the ADOC for wrongful death. Though the state denies to this day that Gadson used excessive force against Davis or any other prisoner, and no charges or disciplinary penalties have ever been brought against him, a settlement payment was made to the Davis family of $250,000.

The steep increase in the cost to the state of Gadson’s lawsuits leads England, the Tuscaloosa representative, to the conclusion that if only an early intervention had been made, then maybe Davis’s life might have been spared. “We missed a lot of opportunities, as the settlement figures kept on rising, to insist on consequences, on repercussions, and maybe save somebody’s life.”

England is calling for disciplinary action against Gadson. But he also stresses that the officer is just a symptom of a larger problem.

“This is just the tip of the iceberg. Many more people will feel emboldened by such lack of accountability.”

As for Gadson himself, he now works at Bibbs correctional facility in Brent, Alabama. The Guardian was put through to his unit as he was serving on a Sunday shift, and he picked up the call.

Did he have anything to say about the allegations of brutality made in the 26 civil lawsuits, or in response to the mounting calls for his dismissal?

“I can’t tell you nothing,” he said in a calm, neutral voice. “I still work with the department of corrections, you probably want to talk to them.”

Then the phone went dead.

3 months ago

51

3 months ago

51