It was the one scandal that Donald Trump seemed unable to shake. No matter his best efforts to convince his supporter base that there was nothing to see here, the demands for the administration to release every document it had on the child sex offender Jeffrey Epstein only grew.

Yet even after the most shocking revelations in the latest drop about Trump’s inner circle – involving everyone from Elon Musk to the Maga honcho Steve Bannon to the commerce secretary, Howard Lutnick, not to mention Trump himself – so far, it seems, the administration has escaped largely unscathed. Nobody has resigned, nobody has been fired, and certainly there is no sign that the US president is going anywhere.

There is, however, one political establishment that the Epstein scandal has shaken to its core – in the UK, where revelations in the files have sent a shock wave through the governing party that threatens to topple it entirely.

Although the former Prince Andrew, the brother of King Charles, is the best known Briton to entangle himself in Epstein’s web, there is another figure who has brought the scandal back home with him.

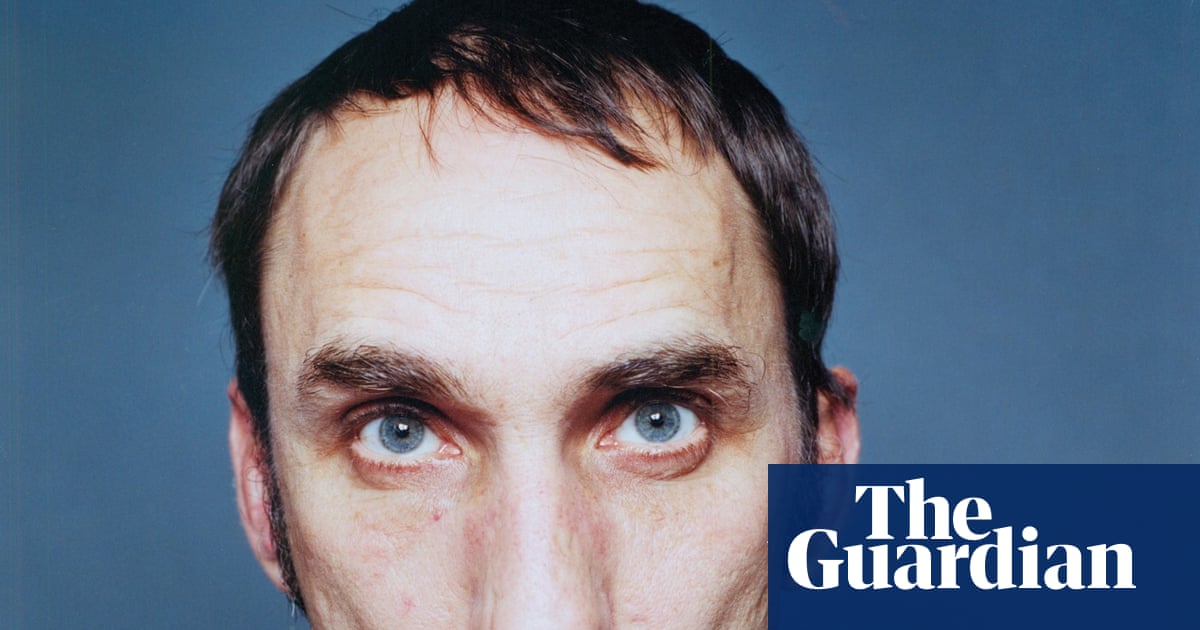

Peter Mandelson is another man with “prince” in his title, though his “Prince of Darkness” nickname was coined to reflect his reputation for being a master of the political dark arts. Few people in British politics have had careers as colourful and turbulent as his. Few people have managed to return from the political wilderness in the way he has.

There may be no coming back from this latest scandal.

Police in London launched a criminal investigation this week into allegations that Mandelson – who most recently was the British ambassador to the US, but whose history at the heart of British politics is long and laden with scandal – shared sensitive information with Epstein while serving as the government minister for business in 2009.

Mandelson, 72, is accused of leaking government emails and market-sensitive information in the aftermath of the financial crash – including alerting Epstein that the British government would soon act to prop up the flagging euro. Separately, Mandelson and his now-husband apparently received several payments totalling at least $75,000. The whiff of selling government secrets is acrid.

He has now quit the ruling Labour party, but the bleeding may not stop there: Keir Starmer, the prime minister, faces serious questions about why someone as clearly risky as Mandelson was ever allowed back into the fold.

To many in the UK, Mandelson is the long-running embodiment of the New Labour movement, having held high-profile roles in the Labour party over four decades, from strategist to government minister. Perhaps most crucially, he is perceived as a key figure during the remarkable run of electoral success under Tony Blair’s centrist turn in the 1990s that helped bring Labour back in from the cold of the Conservative party’s 18-year grip on power.

In an attempt to distance himself – and explain why he hired Mandelson despite having some knowledge of his links to Epstein – Starmer told parliament in London on Wednesday that the politician had “betrayed our country”.

“He lied repeatedly to my team, when asked about his relationship with Epstein before and during his tenure as ambassador,” the British leader said. “I regret appointing him. If I knew then what I know now, he would never have been anywhere near government.”

Yet Mandelson had already been forced out of government twice before: in 1998, when he resigned as trade and industry secretary after failing to disclose that he secretly received £375,000 to buy a house in London from a colleague who was being investigated over his business dealings; and in 2001, when he stepped down as Northern Ireland secretary after being accused of pulling strings to get a British passport for an Indian billionaire who had pledged £1m towards the Millennium Dome project that Mandelson was heading.

Starmer brought him back to advise on how to win the 2024 election anyway, and after Labour’s landslide victory the prime minister chose Mandelson to head the British embassy in Washington. Within a year, Mandelson was fired after emails were published showing he maintained a friendship with Epstein. The latest cache of Epstein documents released by the US Department of Justice makes the previous allegations seem almost quaint by comparison.

Still, with Mandelson being such a long-running presence in the Labour party, the impact of his fall from grace has been widely and deeply felt. Wes Streeting, the health secretary, who has made public his own designs on the leadership, said on Wednesday that he felt personally shaken by the revelations about Mandelson, who had mentored and backed him as a rising parliamentarian.

“I cannot state strongly enough how bitterly that betrayal feels for those of us in the Labour party,” he said, “who feel very personally let down and also feel that he, as well as betraying two prime ministers, betraying our country and betraying Epstein’s victims, has fundamentally betrayed our values and the things that motivate us and the things that brought us into politics, which is public service and national interest, not self-service and self-interest.”

Even his own MPs have warned that Starmer’s days as prime minister are numbered, particularly after he admitted in parliament that he knew about Mandelson’s friendship with Epstein before his appointment. “The most terminal mood is among the super-loyal,” said one MP, while another said of Starmer’s admission: “You could feel the atmosphere change; it was dark.”

But while calling Starmer’s judgment into question, the scandal also appears to have set alight a more fundamental anger at his leadership. His internal critics accuse him of lacking a political and intellectual core, enabling others to manipulate him to their own ends. The tale of how Morgan McSweeney, Starmer’s chief adviser, persuaded him to appoint an already compromised character to one of the most sensitive jobs in government, only to see that decision go spectacularly but foreseeably wrong, is held up as another piece of evidence against him.

All this discontent plays out as Nigel Farage, the Trump supporter whose hard-right Reform party has led polls for months, looms in the wings.

The main message that permeates to voters not following the intrigue in Westminster could be simply that the rot in the British establishment runs deep.

Epstein killed himself in a jail cell in 2019 while awaiting trial on US federal sex-trafficking charges, but his death has done nothing to quell the questions about the high-profile and rich elite he mingled with on both sides of the Atlantic. Richard Branson referred in an email to Epstein’s “harem”. Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor had already been stripped of his titles last year after the posthumous publication of a book by Virginia Giuffre, an Epstein accuser who died last April, but the latest photos, showing him smiling and kneeling on all fours over an unidentified woman on the floor, are a further blow to the British monarchy’s respectability. (Mandelson himself served in a royal position until just recently, on the privy council, a largely ceremonial committee of senior officials that advises the king.)

In the US, Todd Blanche, the deputy attorney general (and Trump’s former personal lawyer), has declared that last Friday’s dump of roughly 3.5m files – out of an estimated 6m total – means prosecutors’ review into the Epstein case “is over”, though survivors beg to disagree. In the UK, the fallout may have just begun.

3 weeks ago

33

3 weeks ago

33