The 88-year-old actor has appeared in more than 100 films, playing everyone from presidents to prisoners. Here, he reflects on AI’s ‘robbing’ of his voice, not believing in Black History Month – and why he’s nowhere near retirement

In a dishonest age when truth is under siege, media attention shatters into a thousand shards of glass and nothing is quite what it seems, what could be more precious than a voice of authority? Cue Morgan Freeman, an actor who has portrayed a US president, Nelson Mandela and the Almighty, and replaced Walter Cronkite on the voiceover introducing the CBS Evening News. If John Gielgud’s baritone was described as being “like a silver trumpet muffled in silk”, Freeman’s is like rich wood polished to a quiet shine.

It was less God’s gift than the product of hard work, thanks to an inspiring voice and diction instructor at his community college in Los Angeles. “If you’re going to speak, speak distinctly, hit your final consonance and do exercises to lower your voice,” says Freeman, dapper in light jacket , via video call from New York. “Most people’s voices are higher than they would be normally if they knew how to relax it. He taught that sort of thing. It was Robert Whitman: I will never forget him.”

Yet the 88-year-old’s signature voice is no longer entirely his own. Hollywood is reeling from artificial intelligence that can replicate the way actors look and sound. The late James Earl Jones consented to the use of AI to replicate his voice as Darth Vader after he stepped away from the role. Freeman has not. “I’m a little PO’d, you know,” he says. “I’m like any other actor: don’t mimic me with falseness. I don’t appreciate it and I get paid for doing stuff like that, so if you’re gonna do it without me, you’re robbing me.”

Has it already been happening? “Well, I tell you, my lawyers have been very, very busy.” They have already found cases and are pursuing them? “Many, yeah. Quite a few.”

Freeman is equally unenthusiastic about Tilly Norwood, an entirely synthetic person regarded as the first “AI actor”, who was officially unveiled in September. “Nobody likes her because she’s not real and that takes the part of a real person, so it’s not going to work out very well in the movies or in television … The union’s job is to keep actors acting, so there’s going to be that conflict.”

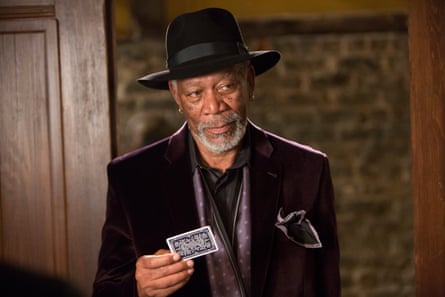

Freeman is here to talk about Now You See Me: Now You Don’t, the third in a trilogy of films about a group of illusionists called the Four Horsemen who use magic tricks to pull off audacious heists. He has a cameo role as magician Thaddeus Bradley, who was a foe in the first movie, an ally in the second and has now evolved into a mentor who shares a country pile (filmed at a 150-year-old mansion near Budapest) with a hall of mirrors and Harry Houdini’s straitjacket. Indeed, far from embracing AI special effects, the director Ruben Fleischer went in the opposite direction, bringing in illusionists to teach the cast authentic tricks.

Freeman has always appreciated hard-earned craft. His beginnings were humble: his father was a barber, his mother was a teacher. He was born in Memphis, Tennessee, and spent most of his early years near Greenwood, Mississippi, in the Jim Crow south. From a young age, he knew what he wanted to do. Saturday matinee cowboy serials lit the spark.

By 12, he had won a statewide drama competition; in high school, he performed in a radio play in Nashville. “I had the most encouraging teachers you could imagine,” he recalls. “One of my teachers told me, you can go anywhere and do anything you want.”

There was a potential alternative timeline, however. “I never had moments of self-doubt about it but, when I was a teenager, I was fascinated by flying so, when I graduated from high school, I went into the air force with the idea at the time of becoming a fighter pilot.

“That lasted until I got into the cockpit of a trainer and had that epiphany that ‘this is not what you want’. It turns out, I was just in San Bernardino, at Norton Air Force Base, being discharged and only a 45-minute bus ride from Los Angeles, California. Fate is the hunter.”

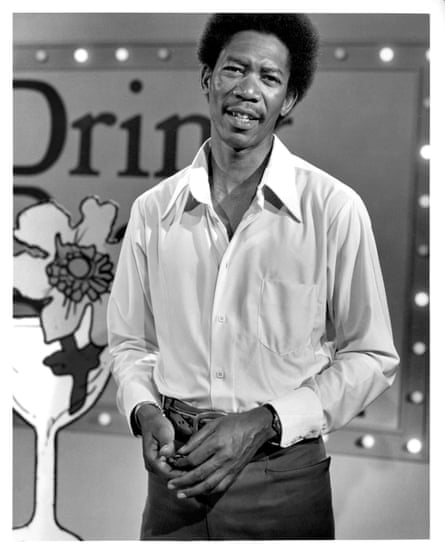

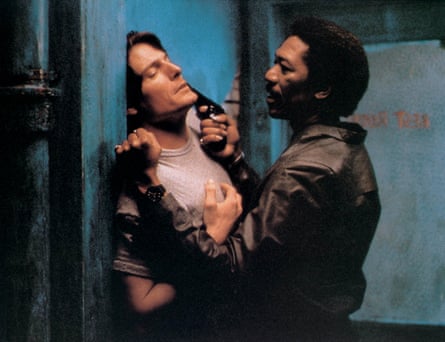

From Amistad and Seven to Unforgiven and The Dark Knight, he has appeared in more than 100 films along with dozens of TV dramas and documentaries. In the 1970s, that included 780 episodes of the children’s series The Electric Company. His big break in Hollywood did not come until 1987, when he was nearly 50, playing a vicious pimp in Street Smart, and earning a supporting actor Oscar nomination.

Two years later he starred in Driving Miss Daisy (reprising his stage role as Hoke Colburn, the chauffeur for a Jewish widow) and Glory, about an African American regiment in the civil war. Since then the hits have kept flowing. “If you do something that’s well received and it lasts years, people talk about the fact that you were in that, so it feels nice,” Freeman reflects. He must get that a lot with The Shawshank Redemption? “Heavens, yes,” he says with a chuckle. “It’s like I was not ever in anything else.”

In Shawshank, he plays a seasoned prison inmate who befriends a rookie played by Tim Robbins. The movie initially flopped at the box office when it was released in 1994, but rallied on VHS video. It is now the No 1-ranked movie on the Internet Movie Database’s Top 250 chart, and in 2006 it was voted the greatest movie of all time by readers of Empire magazine. Just as Jaws or Star Wars are unthinkable without John Williams’ scores, Shawshank would not be half the film without Freeman’s wry narration.

Freeman has his own thoughts about the film’s popularity: “I always say that it’s a movie about a love affair between two men, in that they had their ups and downs and ins and outs. And it’s something about the fact that they were in prison and experiencing this hope, redemption, resilience. Somehow that movie has grabbed the consciences of people all over the place, everywhere.

“When the movie first came out, it didn’t do well at all. You know why? ‘Shawshank Redemption’ – [people] couldn’t remember that. ‘Saw this great movie. It was the Shank … Shim … Shanks … something like that.’ If you don’t get word of mouth, that’s it, you’re dead in the water. It’s as simple as that.”

By this time, Freeman was already well into his streak of documentary voiceovers and authority-figure roles, from God (in 2003’s Bruce Almighty and its 2007 sequel Evan Almighty) downwards. Biblical gravitas had become his brand, you could say.

He’s not sure how he feels about that: “Gravitas, yeah. I don’t know, I’ve done comedies. But I’ll take it. It works for me, so no arguments.” He laughs. “It was interesting, though, the outcome of playing God in the movies. Audiences bought it. I mean bought it. I walk into a room and they say: ‘God just walked in.’ I say something, they say: ‘Oh, it’s the voice of God.’ That went on for the longest time. Ooooo-Kay! Be careful there.” That must be a lot of pressure? “I vociferously avoid the pressure. It’s like, be cool, hold that down, don’t try to convince me that that’s who I am.”

Freeman won a best supporting actor Oscar for his role as a gym assistant and former boxer in the Clint Eastwood sports drama Million Dollar Baby (2004). Five years later, teaming up with Eastwood again, he was Oscar-nominated for his portrayal of Mandela in Invictus (2009).

It was the story of how the South African president used the power of sport to heal the scars of apartheid, specifically by embracing Afrikaners’ cherished sport, rugby, as South Africa hosted the World Cup in 1995. Freeman says of Mandela: “When his book, Long Walk to Freedom, came out and he had a press conference, a reporter asked him flat out: ‘If your book becomes a movie, who would you want to play you?’ He said Morgan Freeman.”

Anant Singh, a film producer who had bought the rights to Long Walk to Freedom, put the two men in touch. “I told him [Mandela], if this happens and I do get to play you, I want to have access to you because I need to hold your hand. And he made that happen. Any time we were within proximity of each other, I was able to go and spend time with him and literally hold his hand and listen to him. Playing him was just a joy. I think I almost sounded like him.”

He remembers Mandela, who died in 2013, as a man of modest ego. “We screened the movie for him and he said: ‘Well, maybe now they’ll remember me.’ Humble: that was Mandela. He didn’t get any different in his persona outside prison from what he had spent the whole 27 years in.”

Freeman has had his fair share of flops too, of course. Not least among them Brian De Palma’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, released in 1990, co-starring Tom Hanks, Bruce Willis and Melanie Griffith. Hotly anticipated at the time, it received a critical mauling and has now achieved a near-mythic notoriety.

Asked if he has learned lessons from such failures, Freeman replies: “I don’t know if I actually can say I’ve learned a lesson. What I try to do is good work; do your job and the rest will take care of itself. I don’t know if there was a lesson that I learned while working. I think it was a lesson I’d known all along. I started acting in elementary school so I was always going to do it, whether I thought I was or not.”

The indefatigable Freeman endorsed Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential bid and recorded a voiceover for the video introduction of presidential candidate Hillary Clinton at the Democratic National Convention in 2016. In recent years he has spoken out against the terms “Black History Month” and “African American”.

Does he still feel that way, now that Donald Trump has set about rewriting Black history from the White House? “David, you’re opening up a can of worms here with me. No, I do not believe in a Black History Month. There’s something about it that separates it from American history. I don’t mind being called a Black man: that’s what I am. I don’t want to be called African American. I’m not African and that’s the bottom of it. That’s all I say.”

Pressed for his thoughts on Trump’s second term, Freeman hesitates, then mutters, “I don’t want to talk about politics,” while publicists for the film, audibly uncomfortable, stage an intervention: “Hey, David, we need to keep this movie-focused.”

In 2008, Freeman’s left hand was paralysed due to nerve damage from a car accident in Mississippi: his vehicle flipped multiple times and he had to be cut out by emergency crews. He wears a compression glove on the hand to help with chronic pain and keep blood flowing. That put an end to him piloting a private jet. Freeman had learned to fly and earned his licence in 2002, going on to own at least three planes. It was not quite his teenage dream of becoming a fighter pilot but did prove convenient for commuting from Mississippi to Hollywood. “You need two hands to fly,” he says matter-of-factly.

He has now been screen acting for more than six decades but has little interest in retirement. “Sometimes the idea of retirement would float past me but, as soon as my agent says there’s a job or somebody wants you or they’ve made an offer, the whole thing just boils back into where it was yesterday: how much you’re going to pay, where we’re gonna be?

“The appetite is still there. I will concede that it’s dimmed a little. But not enough to make a serious difference.”

2 months ago

48

2 months ago

48