All my life I’ve been bad at sports. At school I was always successfully “sick” on the annual sports day and had a standing note from my equally averse mother to excuse me from physical education classes due to my “bad foot”. Even after I started exercising regularly in my mid-20s, I never joined my friends’ social netball or football teams.

“Hating sports” was core to my identity. Then, last year, a friend invited me to her birthday “kickabout” – a casual game of football, I gathered. (I believe some call it soccer.) Had we been less close, I might have made my excuses. Instead I turned up to the park, determined to keep as far away from the ball as possible.

To my great surprise, I enjoyed myself. Instead of running down the clock on the sidelines, I got swept up in the game, rooting for my team to score.

None of the other players were sporty or experienced either. Yet, at the pub afterwards, we agreed we’d had fun and wanted to do it again.

A year later, the kickabout is not only still going, it’s grown from five or six friends to a rotating lineup of about 40. Every other Sunday, we play at a proper pitch at our local sports complex. I am, by some distance, the worst on the team, infamous for always instinctively fending off the ball with my hands (though somehow never when I’m actually playing in goal). But I’m also slightly better than I was a year ago – and I would no longer say I hate playing sports.

What keeps me turning up every Sunday? Unexpectedly, it is not the socialising or the exercise. I love the slightly intoxicating sense of challenging myself, with zero expectation – or even hope – of ever being actually skillful.

Why does it feel so good to be bad at something?

“Amateurish” hasn’t always been a pejorative, explains author and activist Karen Walrond. “It comes from the Latin, meaning ‘one who loves’.”

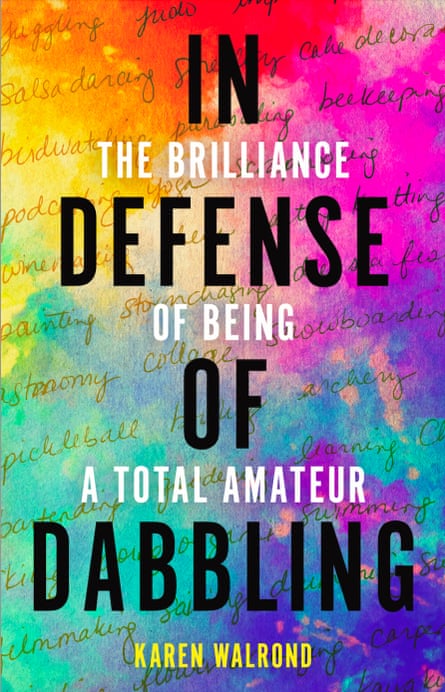

Her new book In Defense of Dabbling makes the case for “intentional amateurism”: finding an activity we’re drawn to but not necessarily naturally good at, and sticking with it anyway. After interviewing dozens of hobbyists, Walrond conceives of it as a regular practice, driven by passion – “something you keep going back to, for the love of it,” she says.

Walrond realised she had internalised the idea that she should be “an expert” at something. Being a generalist is often associated with noncommitment or ineptness, she says, yet many of her most reliable sources of satisfaction were interests she explored for their own sake.

There are two reasons to pursue intentional amateurism. First, it flies in the face of “hustle culture” and the expectation that we should always be productive or self-optimising. Teaching yourself to juggle, for instance, is something you might do simply for personal enjoyment.

Second, even though you might never improve, you’ll inevitably experience benefits, which can flow into your daily life, says Walrond. For example, she has always found meditation difficult, but accesses mindfulness when engaged fully in activities she enjoys.

Mindfulness is among seven attributes by which Walrond defines intentional amateurism, along with curiosity, self-compassion, play, challenge, connection, and wonder or awe. Focusing on these helped her “let go of perfectionism” and appreciate the experience.

Walrond has tried many new activities: swimming, playing piano, making pasta from scratch, calligraphy, surfing, night photography. “I wanted to find something that really captured my soul,” she says.

What stuck was pottery. It meets many of the intentional amateurism criteria, Walrond says. At the wheel, she gets to “shut out the world” and be in the present moment, and also indulge instincts to play. Being part of an ancient tradition inspires awe, while the community at her studio offers opportunities for connection.

It’s now easier for her to “access curiosity, mindfulness and self-compassion,” she says. “I did not expect to find that.”

My weekly kickabout may be similar, Walrond points out. There’s “the connection with your teammates, and certainly play. And the fact that you’re doing it without trying to become a professional footballer means there’s going to be self-compassion.”

after newsletter promotion

As a teenager, I had many hobbies: classical guitar, darkroom photography, conversational French. But I dropped them when I became more focused on my career and realised I would never be especially good at them.

That’s typical of ambitious, career-focused people who might benefit most from embracing amateurism, Walrond suggests. “We think that in order to be fully formed grown-ups, we should put aside some of this ‘kid stuff’ that we’re doing – only to find, years later, that that is actually where your joy is.”

Taking my football commitment seriously, but not putting pressure on myself to perform has helped me to accept myself as I am (not very good at sports), while demonstrating that I can grow and try new things.

Play and exploration without expecting perfection supports a growth mindset, consistently shown by research to boost happiness and wellbeing. “A lot of perfectionism is really related to how you’re perceived by other people,” Walrond says. “Embracing amateurism helps you focus inward.”

More from Why am I like this:

Tellingly, neither of us have trumpeted our new interest on social media – reflecting how precious and separate to our public “selves” it is. Many amateurs Walrond interviewed for her book described wanting to protect their passion from outside judgement, or pressure to improve or monetise. “A lot of people who have really embraced intentional amateurism don’t talk about it,” she says.

One good reason to discuss my new hobby, though, is that friends reveal that they, too, have been dabbling. One showed me a watercolour she’d painted of a horse (“after a few drinks”). Another customises her T-shirts and tote bags. Someone else has been taking drawing lessons in their downtime.

One 60-something woman she spoke to had taken up basketball, which she’d loved as a child. “Nobody’s expecting you to be in the WNBA,” Walrond says. “You can go gentle with yourself.”

In her book, Walrond includes an entire “menu” of activities she still intends to try, inspiring me to steal some for myself (horse riding, learning to play chess).

Simply making the attempt enlarges our lives, by encouraging curiosity and taking us beyond our comfort zone. “There’s something to just stretching yourself a little bit: ‘Let’s see what I can do … What else can I learn, what else am I capable of?’”

I’ve experienced that myself on the football pitch over the past year, going from very bad to better in surprisingly joyful increments. This weekend, in fact, we’re playing our first proper match against another team. I’m sitting it out, to cheer from the sidelines. It’s great to challenge yourself – but part of embracing intentional amateurism, I’ve decided, is also knowing your limits.

-

In Defense of Dabbling by Karen Walrond is out now via Broadleaf Books.

3 months ago

40

3 months ago

40