A gang of young dancers, their black costumes offset by colourful hats, cascade down the sloping roof of Oslo’s opera house for a jubilant routine to a Prince song by the waterfront. The building’s huge glass facade has become an unlikely stage for sculptures, digitally scanned from dancers’ bodies, positioned as if they are plunging into the building like the nearby bathers in the fjord. Inside, there’s an eclectic bill of ballets including one inspired by a painting from the Edvard Munch museum next door. In the wings of the theatre is an installation drawing on the Buddhist Zen symbol ensō. The studio space is screening short films veering from slapstick to the profound.

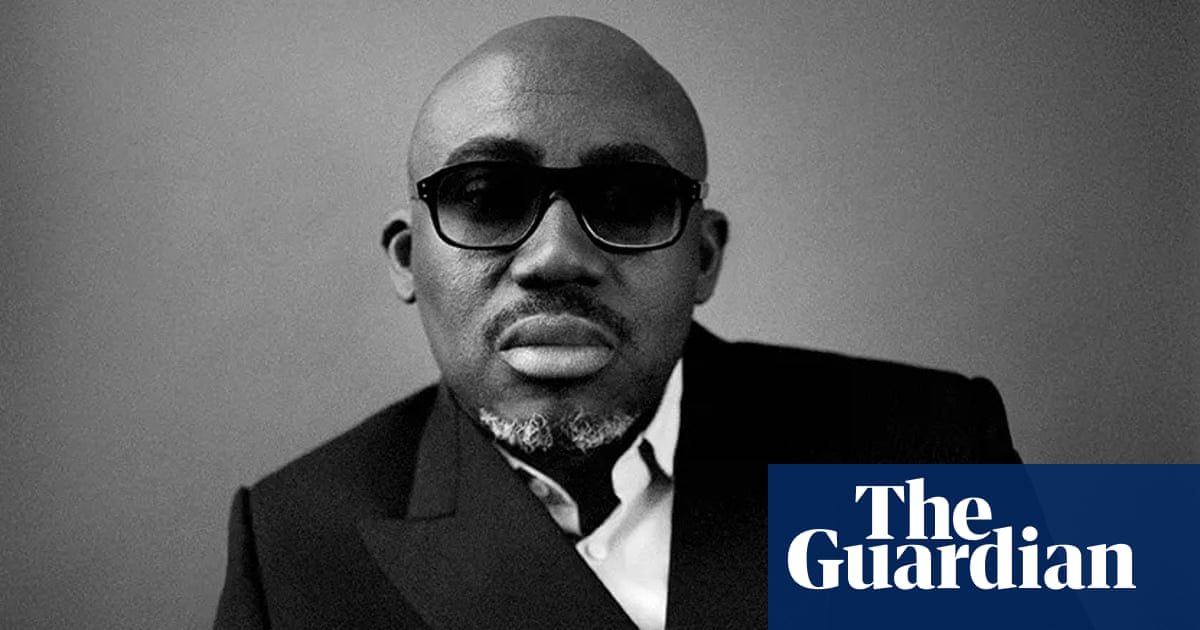

But this sprawling festival, spanning more than two weeks and then partially touring, has a singular focus. These are all works by Jiří Kylián, the Czech choreographer-cum-renaissance man, who in one pre-show discussion declares himself “the happiest boy in the world”. There has never been such a celebration of his work and, he suggests with wry self-effacement, there will probably never be another.

When we meet for coffee, Kylián elaborates on the opportunity given to him by Ingrid Lorentzen who, as artistic director of the Norwegian National Opera and Ballet, enabled the festival. “I’m not a spring chicken,” he says. “I’m 78 and I know that the end of life is nearing. To be able, at my age, to have a major retrospective, but also show new things that I’ve created specifically for this festival, is huge.” After a choreographic career spanning around 100 pieces (a quarter of them now in the Norwegian Ballet’s repertory), it has brought a degree of affirmation, he says. “I must have done something right! I’m not a particularly confident person. It might look like I am, but I’m not really.”

With an impish smile, he adds: “If I had to write reviews about my work, you would not want to read them. I don’t get so easily frightened by critics because I’m my worst critic.” There’s a pause before reconsidering: “My mother was, actually …” He trails off and winces in mock horror at her feedback: “If you do something like that one more time, I will disown you!”

However, it was Markéta Kyliánová – a former child star – who directly inspired her son. “She was a Shirley Temple. A 10-year-old who sold out performances, dancing by herself, with her father accompanying on piano. So it must be somewhere in the genes.” Growing up in Prague, Kylián was swept away by the magic of circus acrobats, became a dancer and began to choreograph. Britain played a key part in his success. In the mid-60s, Jennie Lee – the first minister for the arts in Harold Wilson’s government – visited the Prague conservatoire and saw one of his earliest works. Kylián remembers her saying to him: “I can see that you do not only have it in your legs, but also in your head.”

A scholarship at the Royal Ballet School was arranged. “I met Margot Fonteyn, Rudolf Nureyev, I had the time of my life,” he remembers of his stint in London. John Cranko invited him to work with the Stuttgart Ballet and then Kylián led Nederlands Dans Theater as artistic director from 1975 until 1999, continuing to choreograph for the company until 2009.

But this “Praguer” who has long lived in the Hague is being feted in Oslo. “I was introduced to this country by a composer, Arne Nordheim, who wrote music for me,” he says. The Norwegian Ballet has been staging Kylián’s work for almost 40 years. Oslo’s long-awaited opera house opened in 2008 with his ballet programme. “There is no other house in the world” that could put on this festival’s installations alongside the performances, he says.

Those sculptures bisected by the glass facade, modelled on eight of his dancers and rendered at 138%, provide another way to invite new audiences into this most playful of opera buildings whose openly accessible roof is a popular vantage point. The figures’ positioning, part inside and part outside, brings to mind the uprooted, upside-down tree that is suspended above the stage in Kylián’s Wings of Wax (1997) and continues his interest in transitional states. His choreography frequently gives dancers a winged position like resting marionettes – as in Petite Mort (1991), their heads bowed, shoulders hunched and elbows out, evoking a burden but also an imminent launch to liberation. Entitled Wings of Time, the festival is promoted with a poster of Kylián as if taking flight, with one arm raised alongside its reflection, the image mirroring an airborne gull in the distance. “We are on the way constantly,” he says of this impulse in his work. “I say ‘now’,” he pauses, “and it’s already in the past.”

The other installations on display evoke not just Kylián choreography but his previous productions’ set designs. In the meditative, healing Ensō, set to Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel, a mirror rotates above a calligraphic circle on the floor, casting shadows as well as a latticed light, the mirror rippling with the foaming crash of a wave that recalls the silvery wreckage of John Macfarlane’s set for Forgotten Land (1981). It is that piece, opening with the sound of the wind and featuring a storm of dancers’ feet and elemental percussion, that draws on the century-old Munch painting The Dance of Life. Munch’s depiction of a woman at three ages – enigmatically wistful in youth, solemn in middle age, eventually mournful – gave Kylián goosebumps when he first saw it. “Munch was a troubled soul – that kind of fight with the canvas and with your own problems, it beams out of the paintings,” he says. “I tried to portray it as well as I could with Benjamin Britten’s music.”

The exhibition’s use of backstage areas is fitting for a choreographer who has often challenged notions of where the playing space – and even a production itself – starts and finishes. No More Play (1988), uncannily set to Anton Webern, finds a dancer rolling across the very edge of the stage, arms spiralling into the orchestra pit, and ends with the full cast dangling there. Bella Figura (1995) begins when the audience are still finding their seats as dancers rehearse their moves, Kylián taking the stage to make the odd tweak. The performance gives a supporting role of sorts to the theatre’s layered curtains which in one illusion seem to hold a dancer in mid-air and are used for an effect akin to an iris film technique, framing certain dancers and obscuring others. Kylián plays with other silent cinema tricks in a quirky screen programme featuring his long-term partner, the dancer Sabine Kupferberg, who makes a superb bowler-hatted clown in the short film Between Entrance and Exit from 2013. (That title is telling for a choreographer who loves to bring dancers on in eye-catching ways, such as under billowing sheets.)

Amid his elegantly fluid explorations of time and space, and his dancers’ sensitive partnering, Kylián can rarely resist a comic moment or trompe l’oeil gag such as the freestanding dresses with a mind of their own in Petite Mort. He tells me about his joy at once spotting John Cleese in a restaurant. “I went to him and said, ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’” Cleese immediately played along. “‘Yes, absolutely!’” Kylián told him: “I’m a choreographer and I was inspired by your Ministry of Silly Walks.” Is that really the case? “Of course! The Czechs have a pretty good sense of humour. They’re really pretty crazy.”

His own sense of humour remains intact when we discuss his “more than catastrophic” reception from London’s dance world. That auspicious-seeming arrival in the 1960s was followed by “totally negligible” representation of his works and what he calls the “Royal snub” in the years since his choreographic debut at Covent Garden. In 2022, Forgotten Land was staged by Birmingham Royal Ballet and his piece Gods and Dogs was performed in a mixed bill by NDT at Sadler’s Wells. But he picks up his tablet and shows a calendar of upcoming Kylián productions. “This is where they are doing my ballets in the world.” Dates come up for South Korea, Poland, the US, Albania … “Anywhere except Great Britain! I even got the Laurence Olivier award [for outstanding achievement in dance with NDT in 2000]. That didn’t do the job.” Maybe it’s not for him to answer but does he know why? He leans over and whispers: “I have no idea!”

If Kylián is his own fiercest critic then the late Clement Crisp of the Financial Times came a close second. “I don’t mind to be criticised, but I don’t like to be insulted particularly,” he says of Crisp’s vociferous reviews, then paraphrases the kind of writeup he used to receive in London. “The first piece was by Ashton, it was like that and like that. The second piece was by Kylián, we don’t need to talk about it. And the third one was by Balanchine, it was great.”

How did he find running NDT for such a long stretch? The company rocketed under his leadership but balancing the roles of choreographer and artistic director was surely draining. “It’s really rough. I’d want to do a piece for six dancers and I had 32 dancers in the company. You know what happened? Six happy people and 26 unhappy people. You have to cope with it.”

As well as choreography, he has often provided his own design concepts including, unusually, for the lighting. “A terrible ballet well lit is better than a great ballet badly lit,” he says. “I work very closely with the lighting designers and set designers and composers. I’m one of those who sticks his finger in!” He assesses one of the pieces revived in Oslo. “The choreography is old, OK, it has maybe a bit of an old-fashioned touch. But it fits completely with the music, the choreography and the stage design. If you like it or not is another story. But it fits. It’s made of one mould.”

His approach to the music has changed over the course of his career. “When I was young, I got inspired by a piece of music and tried to do steps as closely to it as possible. But later that wasn’t enough. I have things to say myself.” He did not seek to reflect “what the music is already saying” but rather add another layer. Later on, composers would create specifically for him. “What I do usually is take an existing piece, something extraordinarily beautiful by Beethoven or Mozart or baroque. And then give it to a composer and he recomposes it. I like this bridge between the past and the contemporary.”

In Chapeau, the piece performed as a flashmob by the dance students tumbling down the opera house roof, he doffs his hat to Prince. “I love him. Genius. You know, he was in Holland and I was too shy to approach him and then he died a year or so after.” Chapeau was created for the silver jubilee of the hat-loving Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, where Kylián still resides. He and Kupferberg have been shooting a film on the Dutch island of Terschelling and he sees his future in such projects and visual art rather than creating new work for the stage. “I’m really getting on. The energy is not enough.”

We consider the chicken-or-egg question about the choreographer’s job of matching music and movement. Kylián recalls creating a duet for Whereabouts Unknown (1993) to be used with Charles Ives’s piece Unanswered Question. “I choreographed it on a Sunday and did the whole six minutes in one day. Then I said, OK, let’s try it with the music now. It fit like a glove: they stopped dancing exactly at the end of the music. Sometimes I really don’t know how or why things happen. I look at it and think, I’m not sure if it’s by me.”

He gives me a slightly bashful look about this mysterious, even mystical process which he manages to suggest with both modesty and curiosity. “I felt like it was said through me.”

-

Kylián festival: Wings of Time is at Oslo Opera House until 14 June. Then touring 18-22 June. Chris Wiegand’s trip was provided by the festival.

3 months ago

93

3 months ago

93