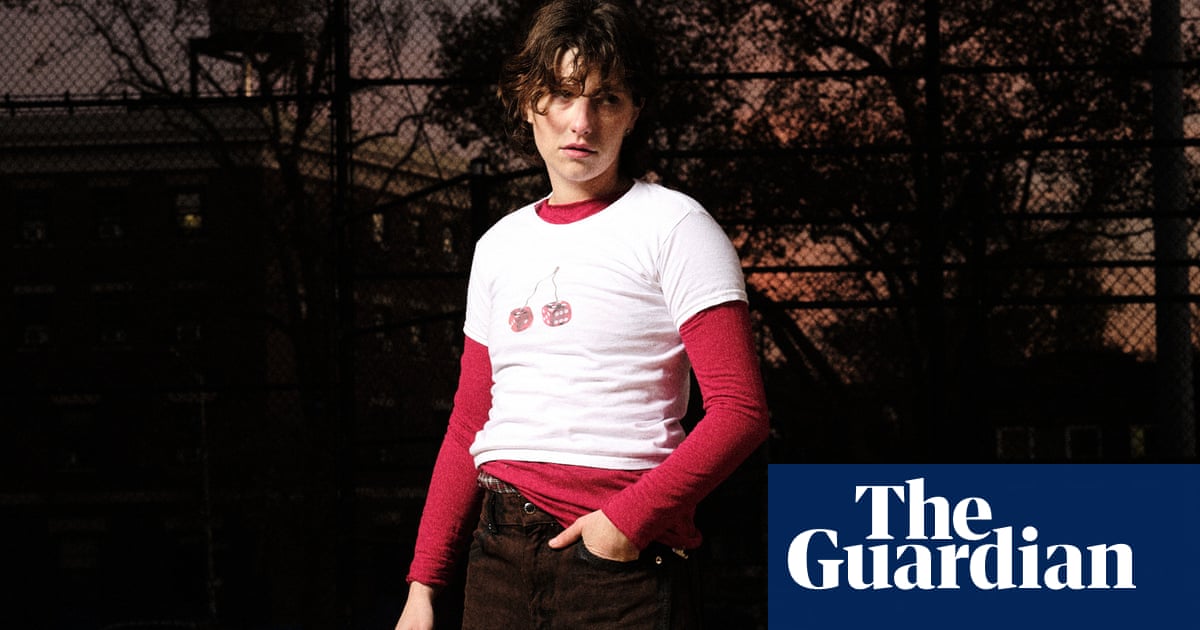

The Admiral Duncan is empty when Jeremy Atherton Lin arrives to meet me, save for a few meandering flies. In the final pages of his bestselling book, Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, Lin visits the old Soho boozer in London with his husband, where they encounter a “despondent” scene: spilled beer, backed-up toilets and a wasted drag queen. Even so, they are charmed by an older couple across the bar and wonder if they’ll be lucky enough to end up like them. The site of a homophobic nail-bomb attack in 1999, the Admiral Duncan is another kind of survivor, and Lin admires it in spite of the mess. Such ambivalence is typical of his memoiristic writing, which spirals outward into digressive analyses of social and political events.

This time, the place is quiet and clean, and Lin has come alone – all of which is probably for the best, since we’re here to discuss his latest book, Deep House: The Gayest Love Story Ever Told. At once more personal and more political than anything he has ever written, it follows him and his partner as they navigate a precarious legal landscape for immigrants and LGBTQ+ people in their effort to build a home and life together.

The couple met 29 years ago at Popstarz, a club night, when Lin was passing through London on a backpacking trip. (In Gay Bar, Lin refers to his partner in the third person, mostly as Famous Blue Raincoat. In Deep House he remains unnamed, though most of the book is addressed directly to him.)

“I depict myself in the book as feeling a little unsure and resistant at first; counterintuitively, this bashful boy is the pursuer,” Lin says. “He’s so lovable that I wanted the reader to feel a little exasperated with me, like, ‘You’re never gonna get any better than this.’” Not long after returning to northern California, Lin seemed to get the message and invited his new British beau to visit. “Famous” came and never left. Overstaying his visa, he became a fugitive for love.

It took a while for them to fully understand the implications of that decision. They struggled to find an apartment given that only Lin – on a writer’s income – could be named on the lease. Every loud noise or bright light outside their door sparked fears of an imminent raid. Accidents were a worry because “we were convinced you couldn’t go into hospital without being deported,” Lin writes.

“We found ourselves laying down roots on a fault line – literally earthquake territory, but also a contentious political framework,” he tells me today. “By 2000, when we rented our first weird, damp apartment, 18 states still had sodomy laws on the books.” They were considered “illegal” in more ways than one.

Lin writes extensively about the case law that led to the 2015 US supreme court decision in Obergefell v Hodges which legalised same-sex marriage across the US. Some of these are relatively obscure, such as Baker v Nelson (1971) and Boutilier v Immigration and Naturalization Service (1967), and he sympathetically details the lives of the plaintiffs, aware that most of them weren’t asking for much. Lin and his partner were less interested in pushing a gay rights agenda than safely crawling back into bed together. “We were half innocent and half obscene,” he writes. “We’d been infantilised by our governments – our ‘twink’ years prolonged.”

At times, this could be a minor thrill. “I can’t deny there was an exhilaration when we went underground,” he tells me. For a middle-class kid in San Francisco’s Mission District in the early 2000s, being undocumented may have seemed like a punk bona fide. Marriage certainly did not – though at the time it was unavailable to them anyway. “A lot of queers, of course, didn’t want in on the historically proprietary and patriarchal institution in the first place,” Lin writes.

Open relationships and polyamory were typical in their urban gay enclave; they duly navigated threesomes and foursomes, including, at one point, with another couple with whom they shared an apartment. The idea of marriage seemed almost too conventional by contrast. Nonetheless, Lin acknowledges that marriage “affords privileges, including mobility across borders. Marriage is, among other things, a passport”. Unable to cross international borders or even state lines without worry, Lin and his partner often felt stuck.

As a white British person, Lin’s partner was perhaps in a more privileged position than those subjected to racial profiling. Lin writes about several suits filed by Asian immigrants, many of them in San Francisco, dating back to a string of racist laws passed by the US government in the 19th century, including the Chinese Exclusion Act. He also tells the story of his own parents, who met in the 1960s after his father emigrated to the US from Taiwan. As a biracial couple, they were only able to marry in Florida because anti-miscegenation laws had been struck down by Loving v Virginia a few years earlier.

It’s unclear if Lin’s father or partner would have been able to remain in the country had Donald Trump been president at the time. Lin says he finished edits on Deep House before Trump returned to the Oval Office in January, and he never expected the immigration crackdown to be this bad. “There are a lot of moments in the book where we think that whoever comes through the door is going to be [Ice],” he says. “That was very far-fetched then. But our paranoia has become the reality.”

In 2007, Lin and his husband relocated to the UK, where they obtained a civil partnership (backdated as a marriage, once same-sex unions became fully legal in 2014). Their timing was lucky. “When my next letter arrived from the UK Home Office, with a visa that established my leave to remain, it was genuinely welcoming, almost chipper,” he notes. “But less than five years later, then home secretary Theresa May would usher in the ‘hostile environment’ policy, a brutally monikered set of measures intended to drive out undocumented denizens that would send ripples of malice toward foreign nationals and minority groups more generally.”

Lin began writing Gay Bar while working a string of retail jobs in London. “I would be writing on the cash register or on the back of the receipts,” he recalls. Eileen Myles was a big influence on his personal, essayistic prose style, as was Michelle Tea (briefly an upstairs neighbour in San Francisco). The 2010s were an exuberant time for London’s gay scene, but also a challenging one for nightlife spaces; by the time the Covid-19 pandemic hit, nearly half of the city’s clubs had already closed. Lin found himself documenting these losses, which eventually became Gay Bar.

That book won the National Book Critics Circle award for autobiography and spent weeks atop international bestseller lists. Lin never anticipated the success. “It’s amazing but also terrifying,” he says. “We weren’t prepared for it.” Meanwhile, “London had lost its sense of wonder”. He and his partner relocated to St Leonards-on-Sea, where he says they often walk along the beach twice a day. When the news cycle or writer’s block is stressing him out, he says, “We go down to the beach and pick up a pebble, name it with whatever is bothering us, and throw it into the water. It’s surprisingly effective.”

As for how Famous Blue Raincoat feels about all the public attention, Lin says his partner is able to read his work with a certain detachment. “I’m working within the idiom of nonfiction, for which the criterion is accuracy, but I’m also writing my remembrance of the past. He’s more forgiving of my confabulations, because he’s an artist. There’s a part of him that’s quite good at loosening up. Although there’s a seven-page sex scene in Deep House that I read out loud a couple years ago, and I think he felt a bit exposed,” Lin admits with a laugh.

Does he have any advice for open relationships? “Communication,” Lin says without hesitation. “So much of the communication that we’ve been fortunate to have is based on implicit trust,” he says. “I think maybe it’s so robust because of our experience feeling like it was us against the world.”

Some wisdom has also surely come with age. “I had come to identify as someone who crossed borders – but slowly understood that adult life had to involve the creation and maintenance of boundaries, a matter of recognising that the world is not just one’s own,” he writes towards the end of Deep House. Marriage may have been a way of protecting their relationship and immigration status, but it also confirmed that they really did want to settle down. If “we go out to be gay”, as Lin writes in Gay Bar, he realised that remaining home with his husband wouldn’t make him any less of a homosexual. “This book is the domestic antidote [to Gay Bar],” he explains. “It’s ‘why we stayed in’. Which is to say, inside the interior of our home, but also inside each other.”

-

Deep House (Penguin Books Ltd, £25) and Gay Bar (Granta Books, £10.99) by Jeremy Atherton Lin. To support the Guardian, order your copies at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

3 months ago

127

3 months ago

127