When the Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz showed her first photobook to a well-known society photographer of the day, he told her “look, a housewife will never be a photographer”.

“That’s what he said!” she laughs. “Imagine … that was my beginning.” Today, aged 81, her work documenting life on the fringes of Chilean society sits in the collections of Tate Modern and MoMA in New York and in 2015 she represented Chile at the Venice Biennale.

Between 1982 and 1987, Errázuriz spent time photographing life in the brothels of Santiago, as trans sex workers fixed their hair, shifted their stockings, refined their makeup and killed time waiting for male clients. It was, she says, a “beautiful” experience. “We talked or we’d have a glass of wine or a coffee. They trusted me.”

Such was her empathetic bond with her subjects, that she even developed a friendship with the mother of two brothers working in one of the brothels. “I dedicated the series to her.” She titled the project Adam’s Apple, and it characterised a career defined by an enduring love of outsiders.

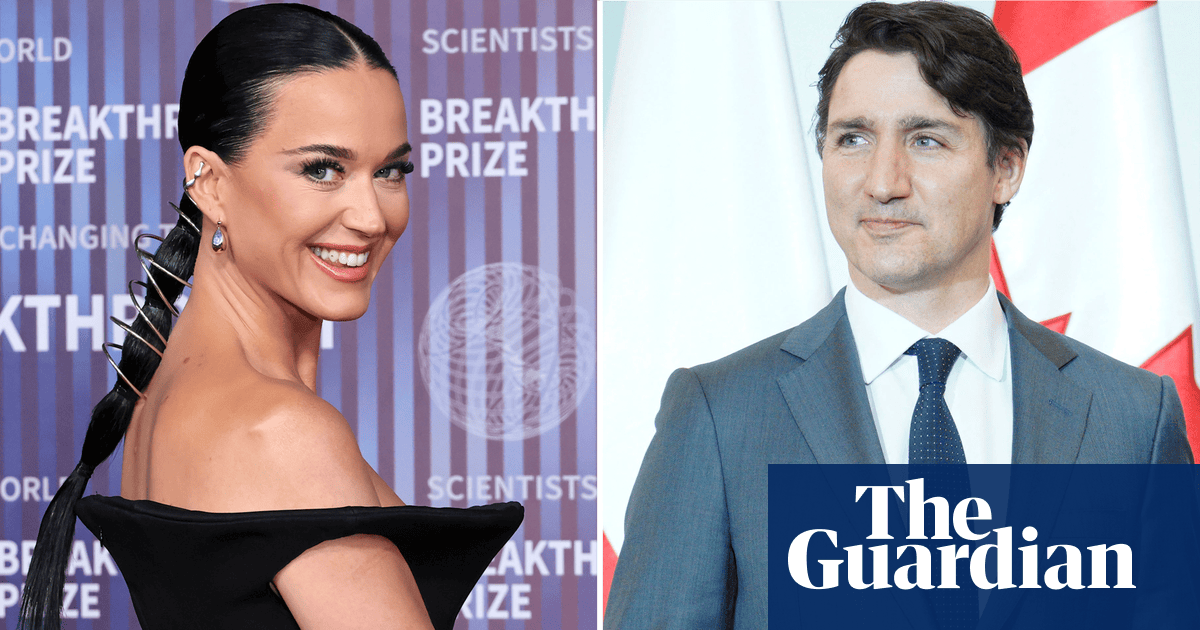

Works from the series can now be seen in her first major solo UK exhibition, Paz Errázuriz: Dare to Look – Hidden Realities of Chile at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes. Other subjects of the 171 photographs on show include psychiatric patients, circus performers, boxers, political activists and the homeless, highlighting the humanity of those living under duress during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

Talking to me over Zoom from her home in Santiago, Errázuriz admits to being nervous about the interview. But she remains an energising presence, even on screen: a huge smile and rippling laugh, spiky hair, she beams through my laptop like a grandmotherly punk.

“My idea is not to shock,” she states. But shock she did. “I was censored for such a long time. For instance, there was a small group exhibition at a museum during the dictatorship and my photograph was taken out. It was a reflection of a naked man in a mirror.” It was artistic, she laughs again, not obscene. “You couldn’t see anything specific.”

Errázuriz was born in Santiago in 1944. Her father, a lawyer, was both strict and traditional. “I never got along with him. He didn’t accept that I studied art when I finished school, so I resented that,” she recalls. A childhood snap taken during her first communion made an impression about photography’s importance as a record. Her head was partly out of the frame. “I was frustrated because friends had very formal photographs. It seemed very unfair.”

She trained as a primary school teacher, studying for a time at the Cambridge Institute of Education in the UK. While teaching in Santiago she began taking pictures, initially of children. “I enjoyed that very much because they didn’t see me. They forgot about the photographer,” she recalls. That project led to her first photobook in 1973 – Amalia, Diary of a Chicken – in which she depicted a household seen through the bird’s shin-high perspective.

She was encouraged in her early work by the book’s editor, Isabel Allende, later the bestselling author of The House of the Spirits and a niece of Salvador Allende, Chile’s president during the early 1970s. “I didn’t know other photographers. I never had the chance to see photobooks in those days. I’m self-taught.”

But everything changed on 11 September 1973 when General Pinochet took power in a coup that saw the country’s air force bomb its own presidential palace. When Pinochet’s troops stormed the building, President Allende was found dead, lying next to his rifle. Isabel Allende went into exile.

Errázuriz stayed. But the coup ended her teaching career; the junta considered her “inappropriate” for the classroom. Photography and family life took its place. She married and had two children. Meanwhile, she began photographing Chileans living on the margins of society, embracing an informal social documentary style with a humanist sensibility. “Little by little, I became more active.”

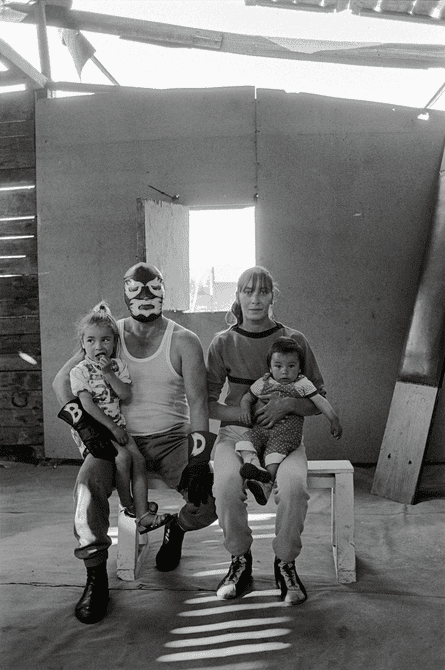

In 1981 she co-founded Asociación de Fotógrafos Independientes, which provided credentials and a membership card as she wielded her camera around town. She went on to photograph vagrants sleeping rough, elderly nudes, riot police, tango dancers, wrestlers, acrobats, dissidents and endangered ethnic groups. All are treated with respect.

Errázuriz compares looking at her old work to flicking through a diary. “It was analogue photography and so you had negatives and you made contact sheets. Film here was very difficult to find, very expensive. You had one roll of film, 36 shots, and when that contact sheet appeared there were so many things on it,” she explains. “The first six strips were of the protests in the street, where the military is doing this or that. Then came the photography of my son, a baby, and then at the end of the sheet is my grandmother’s birthday.”

In the 1980s, Errázuriz volunteered at a charitable centre for people affected by Aids. The crisis decimated the community of sex workers she had photographed. “So many people died. From my project all of them except one,” she says, adding that she remains close to that survivor. “For the past 10 years, the first call I receive in the new year is from him.”

The dictatorship was mercurial, she recalls. In 1987 she began documenting the city’s boxing community. “That, I thought was innocuous,” she says. “But when I went to the place where they trained, they said: ‘Oh no, you cannot come in because women are not allowed here.’” She won them over with “imaginative arguments”.

The last time she showed in the UK it was alongside other international luminaries such as Bruce Davidson, Diane Arbus and Larry Clark in the group show Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins at the Barbican in London. She is thrilled to be back in Britain, a nation of which she is fond, not least because, when Pinochet was placed under house arrest in a Surrey country club in 1998 on charges of human rights violations, “everyone realised, seriously, what he had done because England is such an authority,” she says. “That was the real fall of a dictator.” He told Chileans he’d be home for Christmas but was held for 16 months before, notoriously, the then homesecretary Jack Straw released him on the grounds that he was too ill to stand trial.

Errázuriz is still photographing (albeit on her smartphone, as carrying a camera on the streets of Santiago would be a magnet for muggers). There is widespread poverty, crime and yet more protests, she says, and she is not, perhaps, as primed for the latter as she once was. “You have to run fast. The teargas hurts so much, I discovered that the gas today is totally different to the one 40 years ago.”

Does she think Chile is a better place today than it was half a century ago? “We got rid of the dictatorship. That was the main thing we’ve done. That’s really important,” she says. “But it’s difficult in Chile, really. It’s not exactly what we dreamed of.” When I ask if she still gets pleasure from photographing its people, “Sí,” she says and her face lights up. “When I choose who I’m going to photograph, it’s because, somehow, I like that person. I reflect myself in them. I learn from them.”

Paz Errázuriz: Dare to Look – Hidden Realities of Chile is at MK Gallery from 19 July to 5 October

3 months ago

40

3 months ago

40