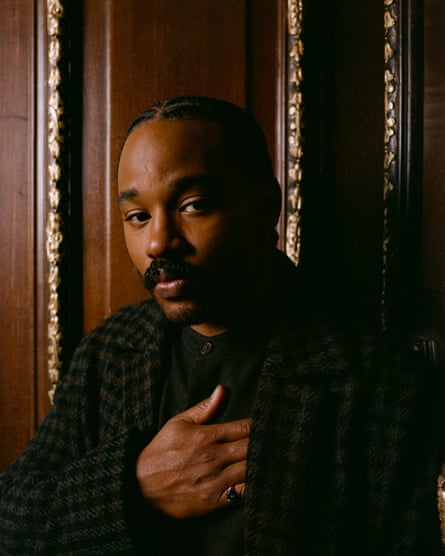

We’re supposed to be talking about movies, but Ryan Coogler has family on his mind when we have our video call – parents, siblings, twins, ancestors and, most of all, his two daughters. “It’s all good, kids not up yet,” the director says in his Oakland drawl. He’s speaking from a New York hotel room, the morning after the premiere of his new movie, Sinners. But, sure enough, 10 minutes into our conversation, his daughters, three and five, come into the room and bundle on to his lap. “Aw, here’s my little ones, bro.” A toy boomerang flies into and out of shot. “Daddy’s gotta work,” he patiently explains. Noises off-screen and doors closing.

Anyway, where were we?

Sinners is Coogler’s fifth feature and, despite being a gory period vampire thriller, his most personal. “I was bringing my whole life to it,” he says. This is his first original story, after a run that’s set him up as one of the most powerful names in cinema. His 2013 debut, Fruitvale Station, chronicled the final day of Oscar Grant, an innocent Black man shot dead by police in Oakland in 2009. It won prizes at Sundance and Cannes and put not only Coogler’s name on the map but also that of his regular leading man, Michael B Jordan. After that came Creed (2015), a reinvention of the Rocky franchise that was way better than anyone expected, even earning Sylvester Stallone an Oscar nomination. Then came the cultural phenomenon that was Black Panther (2018), and its tragedy-stricken sequel, Wakanda Forever (2022). Aged just 38, Coogler is the highest grossing Black film-maker ever, which gave him a certain latitude.

Sinners is set in 1930s Mississippi, close to where his own family originated before moving to California, he explains. The narrative weaves in the recent history of the era: slavery, reconstruction, the first world war; abject rural poverty; the Ku Klux Klan; Christian and African spiritualism; and the birth of the blues. “I’ve been struggling to tell a story that does the great migration for a while,” he says. “It’s a personal obsession of mine, this period of time when Black people were considering leaving the south en masse.” He had already been interviewing remaining members of the “silent generation” for several years, he says, including his own family. The blues element comes from his uncle, who grew up in Mississippi and died in 2015. “We were really close, and he would always listen to blues records – it was his only form of entertainment. I would find myself listening to blues records to remember him. That’s how I got inspired to explore and research, and that’s how I got to this movie.” He’s mindful of his own place in this family history, he says. “So it’s me growing and dealing with my own position, my own mortality.”

He’s talking as if he’s just made a historical documentary, but Sinners is a full-throttle action movie, taking in bloody violence, supernatural mayhem and some rousing musical numbers. Anchoring it all is Jordan in double gangster mode, playing twin brothers Smoke and Stack, who return from Chicago with plans to set up a “juke joint” on the edge of town. Opening night does not go as planned.

This is Coogler’s gift as a film-maker: his movies are deep and soulful but also crowd-pleasing and spectacular. It’s a rarity in today’s movie landscape, and Coogler comes across as a sincere and thoughtful artist, albeit one who’s not all that comfortable being interviewed: he’ll often stammer and stumble trying to express himself. He also takes some of the longest pauses of anyone I’ve ever met.

As to how he manages to make cinema that’s entertaining but not dumb, though, his explanation is simple: “We’re, like, real movie people,” he says. He’s talking about himself and his wife, Zinzi, who is his co-producer. “We grew up going to the movies. We all got kids now but we still end up going, even when we’re busy, at least once a week.”

When he talks about films, he’s talking about family, and vice versa. He really did grow up with the movies: “It’s been in my blood for at least two generations.” He remembers his father taking him to his first cinema when he was five. His father was in his early 20s, doing odd jobs in Oakland, which was still very working class (he later became a probation counsellor; his mother is a community organiser). The movie was John Singleton’s 1991 classic Boyz n the Hood: “He’d heard it was a good movie for Black fathers and sons.” This is the kind of movie Coogler has sought to make, he says: “about a specific American experience, but it translates – everybody gets that movie.” His father took him back the next year to see Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992). He’s proud that he’ll be screening Sinners in the same cinema next week.

Coogler also remembers his first date with Zinzi, when they were still in high school together: they went to see the teen comedy Bring It On (2000). When he interviewed his grandmother (from southern Texas) as research for Sinners, she told him his grandfather (who hailed from Mississippi) had done the same: “He took her to the movies and tried to make out with her. And she told him: ‘Hey, we can do that after the movie. I’m trying to watch this.’”

The twins element of Sinners is also close to Coogler’s own experience. He speaks of the history of twins being othered and mythologised, of the twin deities in the Yoruba culture of his ancestors, and how West Africa still has the highest rate of twin births in the world. But he also speaks of his twin aunts, one of whom is his godmother. “We could tell my aunts apart easily, but they’re completely identical. They live next door to each other to this day.” He also confesses: “I dated these girls that were identical twins when I was in summer camp. But not at the same time, bro!” He was only 10 years old, so it was all innocent, he hastens to add. “But these girls were cute, man – everybody wanted to be with them.”

As for directing two Michael B Jordans, Coogler modestly credits his leading man for differentiating the two characters (Smoke is tough and serious; Stack more easygoing and dandyish). Coogler just took care of the technical stuff, he says. The twins theme fits with the dichotomies of the story – good and evil; the blues and the church; day and night – but it was also a way to refresh his long relationship with Jordan, who has not only featured in all of Coogler’s movies so far, but also directed Creed 3, which Coogler co-wrote and co-produced.

“He’s an incredibly kind man, a humble man, generous, but he does have a raging ambition within him,” Coogler says of Jordan. “If you can offer him something that he hasn’t done before, that, on the surface, is a challenge, you have a better chance of getting his interest – especially with me, because we’ve done so much together.” He wouldn’t describe their relationship as brotherly, but they are like the twins in the movie: “Mike is very like Stack, in terms of his ambition. He’s a wild dreamer. He comes up with incredible ideas and concepts, and oftentimes I’m like: ‘Bro, that’s impossible.’ So we make a good pairing.”

Despite the setting, it is tempting to view Sinners as a commentary on the present day. This is, in essence, a story about Black folks trying to build something of their own, and white folks coming in to try to tear it down (the movie’s chief antagonists are a sinister Irish folk trio, led by Jack O’Connell). At that level it’s a story that reflects its era, not least incidents like the Tulsa massacre in 1921, where a whole Black neighbourhood was razed to the ground by white people. But it could also speak to a modern-day America, where DEI provisions are being rolled back by the Trump administration, Black history is being erased, qualified Black professionals are being fired and white supremacy is apparently back.

In 2022, Coogler was handcuffed and detained at a bank in Atlanta, assumed to be a bank robber, when he was simply trying to withdraw his own money. The issue was quickly resolved, and Coogler would rather not talk about it today, he says.

And as for parallels with the present day, “any direct ties with what’s happening right now are, like, totally coincidental, or ironic”, he says. He wrote the story in 2023. “I definitely couldn’t have predicted what’s happened in our politics in the last few months. I wish I was that smart.”

In a way, though, Coogler’s career stands in direct opposition to the forces now trying to tear American progress down. Fruitvale Station anticipated the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. Now, that movement is in retreat, as the culture war has spread into entertainment: movies that give more space to women or people of colour are routinely piled upon by white so-called fans. Major franchises such as Star Wars, Marvel movies and Disney princess movies have all experienced this.

But if there was ever any credibility to the “Go woke, go broke” maxim, Coogler’s work provides the perfect riposte – particularly his Creed and Black Panther movies, all of which have been hugely successful. Black Panther in particular will be remembered as an extraordinary flowering of Black creativity, in its utopian Afrofuturism, its celebration of African culture and its gathering of talents on screen and off, from the all-star cast, to Oscar-winning costume designer Ruth E Carter, to Kendrick Lamar, The Weeknd and SZA on the soundtrack. It’s no exaggeration to describe it as a cultural moment, on a par with Coogler’s formative movie experiences Boyz n the Hood and Malcolm X.

Making the sequel was much harder, he says, in the face of the Covid pandemic and the death of Black Panther himself, Chadwick Boseman, of colon cancer in 2020. It was a time of “complicated grief”, he says, and the Black Panther team took it like a loss in the family. They got through it by working. “Sometimes it’s actually a relief having something to do, so you can’t sit in that terrible feeling … After we put the movie out, my heart broke almost even more, because I realised all the work had been distracting me from the fact that Chad’s not going to make any more movies.”

Conscious as he is of his identity and heritage, Coogler never set out to make films only for Black audiences. He pushes back on my suggestion that Sinners is simply about white folks tearing down what Black folks have built. It’s more complicated than that, he says. The story also includes Chinese American and Native American characters, and O’Connell’s character is marked by his own history of colonisation back home in Ireland: “I think he has knowledge of what’s really coming for these people.”

Coogler has no axe to grind against Irish folk music, he insists. Quite the opposite, in fact: “Black people love that shit, bro! It’s almost the world’s best-kept secret how much we love that music and that culture.”

Music is the key to Sinners, and, he suggests, to the history of multicultural America. “You realise that ‘genre’ was a totally racist invention,” he says. In the 1920s, white-owned labels began to market blues, jazz and gospel music to Black consumers as “race records”, he explains, “and they built different genres off that. So it’s like, I sing a song, then you sing a song and now they’re different genres? That’s fucking crazy.”

Coogler calls blues music “the most important contribution America has made to global culture … because it’s so true, it’s so pure that it works for everybody. And to me, that is fascinating – that people living under that type of societal situation can make something that had that transcendental impact.”

There’s a memorable musical scene in Sinners where singer Miles Caton’s blues performance literally tears the roof off the joint and rips through the fabric of space and time, bringing together African tribal musicians, Funkadelic-style electric guitarists, even Chinese dragon dancers. This frenzied melting pot of musical styles and cultures is perhaps closer to the real America, or at least how Coogler sees it.

There’s just time to ask about Black Panther 3. Rumours have been circulating. Denzel Washington apparently let slip Coogler was writing a role for him in it. Letitia Wright’s Shuri, who inherited the Black Panther mantle in Wakanda Forever, is set to figure in Marvel’s next Avengers team-up. There’s also a spin-off Eyes of Wakanda miniseries on the cards. Is it going to happen?

“I certainly hope so – I love all those guys over there,” he says. But then his daughters come back into the room. “They’ve come to collect me, bro,” he laughs, as they pull him away. He’s kept them waiting long enough. Movie time is over; now it’s family time.

3 months ago

147

3 months ago

147