Ray Foulk, co-founder

In 1968, when I was 22, my older brother Ronnie got a job as a fundraiser for a swimming pool on the island. I’d done a concert for CND [the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament], so we started talking about doing some sort of festival to raise the money. My younger brother Bill suggested it had to be pop. An agency in London gave Ronnie a list of acts including the Pretty Things, the Move, Fairport Convention, Tyrannosaurus Rex and an American act, Jefferson Airplane. We only had a £750 investment from the Isle of Wight Indoor Swimming Pool Association, but after a friend lent us his £1,000 army pay-off, we managed to book all those bands, sell 10,000 tickets and break even. In the interim, the pool association pulled out because it didn’t like the publicity about hippies, drugs and sex, but they allowed us to use their investment and we were able to pay them back.

That first event in 1968 was pretty shabby – the stage was a couple of flatbed trucks and the caterer ripped us off. We decided to do it again the following year, but properly. Ronnie had got Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding album for Christmas and argued that someone like Dylan would draw people to the island. He got Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman’s number from an underground magazine and called him. Dylan hadn’t performed since his motorbike crash in 1966 so we didn’t get far, but we kept calling. Grossman wanted Dylan to make a big comeback at the Woodstock festival, but the two had fallen out and weren’t speaking. Meanwhile, I’d been getting on well with Grossman’s partner, Bert Block, and one Wednesday night he sent a telegram saying Dylan had agreed to play the Isle of Wight. It felt like winning the lottery. But he wanted me to fly to New York to sign contracts, and said: “Don’t forget the dollars.”

We didn’t have any money, so we approached various monied people. The head of Screen Gems Europe understood how big Dylan was and agreed to invest in us.

Suddenly we had a massive event that pulled in 150,000 people. George Harrison and Patti Boyd came to stay. John Lennon and Ringo arrived on the day. I’ll never forget watching Dylan playing tennis with three Beatles.

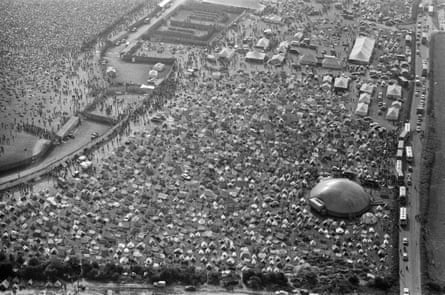

By 1970, us three kids were big-time promoters who could book a raft of stars, and that year’s event attracted over half a million people. The Who were phenomenal, Joni Mitchell triumphant. The Doors’ Jim Morrison was out on bail and they played a moody, oddly moving set in near-darkness. Murray Lerner’s [1996] film about the 1970 event created a false narrative that it was a disaster. Yes, Kris Kristofferson was booed and there were flare-ups with radicals who wanted it to be a free festival like Woodstock, but most people loved it. It’s a myth that Jimi Hendrix played with the stage on fire – it was a firework. That was his last UK performance – 18 days later he was dead.

We had always battled councillors and the like moaning about “kids fucking in the bushes”, drugs and such, and after 1970 new restrictions made it impossible for us to put the festival on again. Still, we’d created a blueprint for the modern festival with camping. In 2002, John Giddings – who had attended in 1970 as a teenager – brought the event back. Today’s Isle of Wight festival is a well-organised entertainment spectacular. In the 60s it was a pilgrimage to see countercultural artists who were singing about making the world a better place.

Arthur Brown, singer, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown

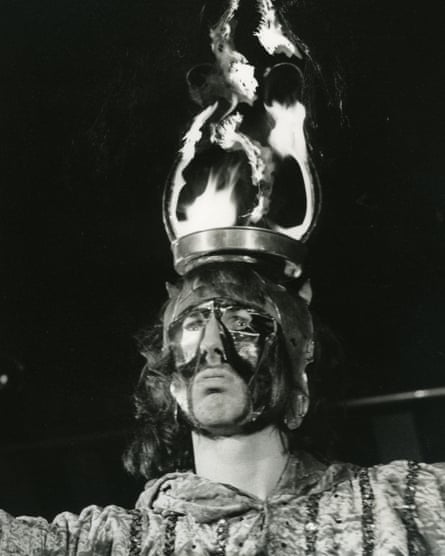

In 1968 we’d just been at No 1 with Fire when we were booked to headline a new festival. But then Jefferson Airplane said they would bring a phenomenal PA system from the US if they could top the bill, so we were bumped to headlining the “Great British groups”.

In those days, crowds loved it if performers were drunk or doing extreme things. I would arrive on stage wearing a helmet with a pie dish on top filled with petrol and our lighting man would throw lit things at it until – whoosh – it went up in flames. At the Windsor jazz and blues festival the summer before, I’d been lowered on to the stage by crane but caught fire from my burning helmet. People poured pints of Newcastle Brown over my head to put me out, so I arrived on stage more like a drowned raccoon than “the God of hell fire”.

At the Isle of Wight, I’d planned to fly in by hot air balloon from Portsmouth, but on the day strong winds in the opposite direction scuppered that. I went on wearing face paint and a crazy costume, which was unusual then – and still is! In the rain I just couldn’t get the helmet to light, so I ended up swearing over the microphone. I was a God of hell fire without any flames, but people loved us.

3 months ago

41

3 months ago

41