What was I thinking? This is not as easy or straightforward a question as I would have thought. As soon as you try to record and categorise the contents of your consciousness – the sense impressions, feelings, words, images, daydreams, mind-wanderings, ruminations, deliberations, observations, opinions, intuitions and occasional insights – you encounter far more questions than answers, and more than a few surprises. I’d always assumed that my stream of consciousness consisted mainly of an interior monologue, maybe sometimes a dialogue, but was surely composed of words; I’m a writer, after all. But it turns out that a lot of my so-called thoughts – a flattering term for these gossamer traces of mental activity – are preverbal, often showing up as images, sensations, or concepts, with words trailing behind as a kind of afterthought, belated attempts to translate these elusive wisps of meaning into something more substantial and shareable.

I discovered this because I’ve been going around with a beeper wired to an earpiece that sends a sudden sharp note into my left ear at random times of the day. This is my cue to recall and jot down whatever was going on in my head immediately before I registered the beep. The idea is to capture a snapshot of the contents of consciousness at a specific moment in time by dipping a ladle into the onrushing stream.

Sounds simple, but what the ladle scoops up is harder to describe than you might expect. Yes, these are my own thoughts, and who should know more about them than me, their thinker? Yet I’m finding that what we know about our own thinking is considerably less than we think.

The beeper exercise is part of a psychology experiment I volunteered to take part in. Descriptive experience sampling is a research method developed by Russell T Hurlburt, a social psychologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas; he has been using it for 50 years – which is to say, his entire career. To give you some perspective, beepers didn’t exist 50 years ago. Hurlburt, trained as an engineer, had to design and build his own unit, on which he holds a patent. It looks like an old-timey pocket radio: grey plastic, with one of those corrugated dials you rotate with your thumb to turn the thing on and boost the volume; the earpiece is flesh-toned, as that term was understood in 1973. For half a century now, Hurlburt has been scrupulously collecting reports of people’s inner experiences at random moments – and just as scrupulously resisting the urge to draw premature conclusions. A die-hard empiricist, he is as devoted to data as he is allergic to theories.

By the time I spoke to Hurlburt, I was starting to doubt my own grasp of what consciousness is. Or, to be more precise, to question whether the theories I’d been working so hard to understand did an adequate job of explaining what actually goes on in my head. It perplexed me that these theories had virtually nothing to say about thoughts – about the contents of consciousness. Most, if not all, of the leading theories maintained that what entered our conscious awareness was perforce important. It concerned competing for work, say, or staying safe in a crisis.

But how do our theories of consciousness account for the banalities, the trivialities and all the seemingly arbitrary bits and bobs of mental flotsam that have no bearing on our survival, yet occupy so much of our waking thoughts?

A neuroscientific perspective on consciousness might tell us something about its neural correlates, but it is unlikely to tell us much, if anything, about the nature of thoughts or the textures of inner experience; it’s the wrong tool for that job. So what might we learn about consciousness if we gave more weight to the view from inside the experience – the phenomenological viewpoint?

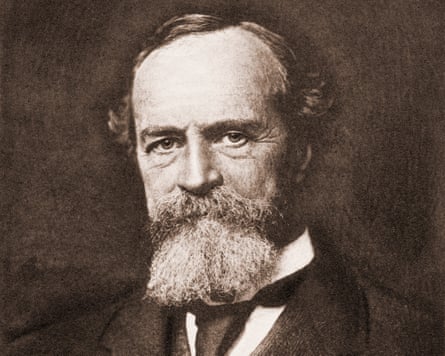

One of the first explorers of the phenomenology of thought was the pioneering American psychologist and philosopher William James. In 1890, James published The Principles of Psychology, a two-volume collection of his lectures on a field that barely existed at that time. One of the most famous lectures presents his account of what he called “the stream of thought” (James used that term and “stream of consciousness” more or less interchangeably). This lecture opens with the bracing words: “We now begin our study of the mind from within.”

James is dogged in his attempts to find words for the most elusive of mental phenomena – up to and including the familiar phenomenon of searching for a missing word or name, the one that feels as though it is right there on the tip of your tongue. “Suppose we try to recall a forgotten name,” he writes. “The state of our consciousness is peculiar. There is a gap therein; but no mere gap. It is a gap that is intensely active.” A sort of ghost of the absent name haunts the empty space in our consciousness, he suggests, making us “tingle with the sense of our closeness, and then letting us sink back without the longed-for term”.

He goes on: let someone propose a candidate for the missing name, he suggests, and even though we have no consciousness of what the name is, we are somehow conscious of what it is not and so summarily reject it. How strange! Our consciousness of one absence is completely different from our consciousness of another. But, he asks, “how can the two consciousnesses be different when the terms which might make them different are not there?” The feeling of an absence in our minds is nothing like the absence of a feeling; to the contrary, this is an absence that is highly specific and intensely felt.

To give the matter a moment’s thought is to realise that James is spot on about mental phenomena such as the missing word, phenomena that are too fleeting or ethereal to name. “Has the reader never asked himself what kind of a mental fact is his intention of saying a thing before he has said it?” I had not, but how curious. This intention is neither a word nor an image; perhaps it’s some kind of vague sensation? Thoughts precede both words and images, James argues, and there is something else – that pregnant absence – that precedes a thought. “A good third of our psychic life consists in these rapid premonitory perspective views of schemes of thought not yet articulate,” he writes. Thoughts glimpsed from some height of awareness but somehow not yet formed, much less put into words or images – this is the subtle terrain James invites us to explore with him.

James is attempting the impossible, which is to somehow step out of the stream of consciousness in order to observe it from its banks. But as he knows as well as anyone, the thoughts we have when we introspect are far from normal thoughts; they are inflected by the very process of being observed as thoughts and recorded in words. Put another way, the very act of sneaking up on our experience becomes part of the experience. A second problem is that our mental bandwidth is limited; psychologists estimate that we can keep only about three to five things in mind at the same time. So however much mental space we allocate to self-conscious introspection is space no longer available to first-order thoughts and perceptions.

Does this mean there is no way, whether theoretical or phenomenological, to investigate consciousness without doing violence to it one way or another? Is there any path around this “observer effect”? These are the questions and doubts that brought me to Russell Hurlburt’s door and made me think that attaching his old-timey beeper to my belt might be a good idea.

Hurlburt’s antipathy toward theory is key to understanding what he’s attempting to do, and why he was so gruff when I told him I was writing about consciousness. (“Good luck with that,” he grumbled.) He treats theory as an illness you might catch, and he strives to keep it out of his research – indeed, out of his mind – lest it infect his sampling process. Since that involves closely questioning volunteers about their inner experiences, the slightest theoretical taint to his questions could easily contaminate the reports of his volunteers and ruin their empirical value.

Hurlburt built his beeper as a way to randomly sample people’s thoughts throughout the day. What he is after in his research is the “pristine inner experience”, by which he means a sample of human thought “unspoiled by the act of observation or reflection”. Like James, Hurlburt acknowledges that the act of recalling and describing an experience is bound to alter it, but he believes that his method can get us closer to the uncontaminated ideal than any other.

The suddenness and intimacy of the beep slices off the moment cleanly and crisply. It often startled me, but I immediately knew what to do: recall and write down my inner experience, or what was going on in my head, a microsecond before the audible blade came down.

Yet that wasn’t as easy as it sounds. Moments in consciousness are not discrete, as James understood; they are often layered and coloured by other thoughts and sensations, as I discovered with my very first beep. It found me standing in line at the Cheeseboard, a neighbourhood cafe and bakery, at 9.24 on a Tuesday morning. I took out the little pad provided by Hurlburt and jotted down this thought: “Deciding whether or not to buy a roll.” I know, not terribly exciting, but it seems very few of my mental contents are. I was thinking ahead to lunch and wordlessly deliberating whether to buy a fresh roll for a sandwich or do the responsible thing and use up the heel of bread I had at home.

Yet deliberating “fresh new roll” v “old heel of bread” wasn’t the only thing going on in my mind at that moment. I was also conscious of the pattern of the skirt – an unflatteringly large plaid – worn by the woman standing in line ahead of me. Was that observation part of the moment in question, or did it come immediately before or after? I couldn’t say for sure. (How long does a moment in consciousness last?) And what about the pervasive smells of freshly baked goods and cheese? These both preceded and followed the moment under examination, but were they present to my awareness at the beep?

After each sampling day, Hurlburt and I would meet via Zoom for a gruelling follow-up interview. Hurlburt would be in his office in Las Vegas, dressed casually in a sports shirt, wisps of whitish-grey hair across his scalp. He seldom smiled, paused interminably and often wore a quizzical look just this side of sceptical.

Every session started out with some variation of Hurlburt’s central question: “What was in your experience (if anything) at the moment of the beep?” However I answered it, Hurlburt proceeded to patiently chisel – sometimes jackhammer – away at the distortions of recollection, presupposition, theory, context, wording and self-regard that inevitably coloured my reports. The first day of beeps was the messiest. After I described the moment in line at the Cheeseboard, the too-big plaid skirt and the cheese-and-bread smells, Hurlburt pressed me: “So is all that stuff directly before the footlights of consciousness at the moment the beep interrupts you?” Yes, I thought, but under questioning, I realised I probably didn’t start attending to the smells until after the beep, when I was reconstructing the moment. “So is it actually at that moment that I was aware of the smells? I honestly don’t know.”

I finished most of our hour-long sessions feeling deflated. I’d been thinking hard about consciousness for several years, and had been conscious for much longer than that, but I clearly wasn’t very good at observing and reporting on the contents of my own consciousness. Under the press of Hurlburt’s questions, I realised I wasn’t even sure whether my inner experiences consisted of words or images or something else entirely – and if words, whose words were they, exactly?

I also got down on myself for the sheer tedium of my inner experiences. Most of my beeps caught me in moments so banal and quotidian as to be embarrassing. Where were the big thoughts about writing or the reflections on the state of the world or the contemplations of my relationships and emotions? Where were the daydreams and mind-wanderings, the worries and ruminations? And what about the sexual fantasies? (My inner thoughts would have put Dr Freud to sleep.)

Herewith I present a sampling of my collected beeps, chosen more or less at random. A beagle, off leash, is walking toward me on the sidewalk. Beep: Wonder if he’ll come close enough to let me pet him; hope so. I’m at the car mechanic, picking up my car after it’s been serviced (to the tune of $2,400). Eddy, the mechanic, wants to show me how the finish is beginning to oxidise; he recommends I reach out to this specialist he knows who can buff and wax it. “He makes house calls.” Beep: Oh great. How much more is this going to set me back?

My wife, Judith, and I are seated on the couch, reading. She stops to read aloud a passage from The Man Without Qualities: “Knowledge is a mode of conduct, a passion.” Beep: Huh? What does that even mean, and why does she think I need to hear it? I’m sitting at the kitchen table, having just closed my laptop. I look out of the window at a live oak tree in the garden in the rain, and I think, What am I thinking? Anything? What would I say if the beeper went off now? A second or two later, it does. Beep: Pretty scene.

I thought I was failing the experiment, but at the same time, I also thought there were ways in which the experiment might be failing me. As the last beep suggests, wearing the device subtly (and not so subtly) altered my inner experiences. And while the interviews definitely taught me skills useful for noticing various aspects of my inner experience, I found myself trying to please Hurlburt by making sure to ask myself the kinds of questions he would probably ask. Words or images? If words, precisely which ones? If images, colour or black and white? Learning this catechism seemed to work against the objective of pristine thoughts captured in the wild.

So is the effort of sampling inner experiences a game worth the candle? The half century Hurlburt has spent collecting samples of conscious experience has yielded some interesting and important findings. The first finding, to which I can personally attest, is just how little most of us know about the characteristics of our own inner experiences. “That’s probably the most important finding that I’ve got,” Hurlburt said.

Inner speech, which many of us – including many philosophers and neuroscientists – believe is the common currency of consciousness, may actually not be all that common. Hurlburt estimates that only a minority of us are “inner speakers”. So why do we think we talk to ourselves all the time? Perhaps because we have little choice but to resort to language when asked to express what we are thinking. As a result, we’re “likely to assume that’s the medium for inner thought”. We’ve also read so much about the importance of words to thinking – words written by philosophers and scientists (not to mention novelists) for whom it may well be true.

But that doesn’t make it true for everyone. Fewer than a quarter of the samples that Hurlburt has gathered report experiences of inner speech. A slightly lower percentage report either inner seeing, feeling, or sensory awareness. Still another fifth of his samples report experiences of “unsymbolised” thought – complete thoughts made up of neither words nor images.

The fact that there is so much variation from person to person in our modes of thinking is itself an important finding of descriptive experience sampling. Most of us assume that our inner lives must be substantially similar – not necessarily in content but in the form our thoughts take. Hurlburt has suggested that we fail to recognise the diversity of thinking styles because we lump them all together under that single word – thinking – and assume we mean the same thing by it, though in actuality we don’t.

In the end I decided that Hurlburt’s relentless focus on the discrete moment obscures as much as it reveals about the ever-shifting contents of our minds. A sample drawn from the stream of consciousness might tell us interesting things about the chemical composition of the water, but it tells us nothing about the stream’s dynamics – about the currents of feeling and eddies of thought that make up our mental lives. My stream of consciousness might be shallower than some, as Hurlbert informed me, but I have no doubt that it flows even so.

I can count on one finger the number of times I’ve encountered the prefix un‑ in my travels through the world of consciousness research. Nobody talks about the unconscious. It seems this is yet another intellectual fence that has been erected around the science of the mind, confining its focus largely to conscious perception in the here and now. Ask about the unconscious and most neuroscientists will acknowledge its existence, grudgingly, before going on to explain that consciousness is hard enough to study as it is, without complicating the matter by bringing in something as elusive and ill-defined as unconsciousness. However, I managed to find one notable exception.

Kalina Christoff Hadjiilieva, a Bulgarian-born psychologist at the University of British Columbia, like Hurlburt, has little use for theories of consciousness that ignore thoughts and inner experience. But unlike Hurlburt, she believes that the focus on discrete moments of consciousness tells us very little, and precisely nothing when it comes to the dynamics of thought – the movement of the stream of consciousness and, crucially for her, its deepest wellspring. Where in the brain do our thoughts come from, and how do they arise?

“Consciousness is just one function of the mind,” Christoff Hadjiilieva told me during one of a half-dozen interviews, this session over a cup of tea in my garden. A jazz pianist, she was in town for an improvisation workshop. She has deep-set eyes and an easy smile. Speaking with the faintest of accents, she displayed an outspokenness and candour that occasionally took me by surprise. “To focus on conscious thoughts is like focusing on the leaves of a tree and trying to understand them in isolation,” she said. “The tree is the mind, and there’s a lot more to the mind than consciousness.”

Christoff Hadjiilieva has written detailed phenomenological accounts of daydreaming, creative thinking and thoughts that arrive seemingly out of nowhere. But a purely descriptive approach to mental experience has its limitations. That’s because phenomenology stops at the edge of consciousness, and Christoff Hadjiilieva wants to peer over that edge. She calls her hybrid approach “neurophenomenology”. It combines self-reporting of mental experiences with brain imaging to learn which brain networks are implicated in each of our various forms of thinking.

The field’s focus on conscious perception has led it to overlook the 30-50% of mental experience that is fed to us by our minds rather than our senses, Christoff Hadjiilieva contends. Most of this time is spent in mind-wandering, daydreaming and rumination. For her, a wandering mind is not just off task but unconstrained, as in the dictionary definition of wander: “to move hither and thither without fixed course or certain aim”.

To identify the neural correlates of these different modes of thinking, Christoff Hadjiilieva puts people in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanners and asks them to press one button when it feels like their thoughts are moving freely and another button when it feels like their thoughts are somehow constrained. She has come to see the conscious mind as seesawing between constrained and unconstrained thinking. In brain scans, this phenomenology shows up as a contest between the executive control network at the front of the cortex and the default mode network further back in the brain.

In an attempt to pin down the unconscious origins of our conscious thoughts, Christoff Hadjiilieva conducted an experiment with long-term meditators (mindfulness practitioners). These are people who have been trained to still their minds but also to notice the precise moment when that stillness is broken by an errant thought, which Christoff Hadjiilieva found happens every 10 to 20 seconds or so even in these trained minds. (“The big lesson of meditation,” she said, “is that the mind cannot be controlled.”)

Volunteers were instructed to meditate while inside the tube of an fMRI machine and press a button whenever a thought arose. Christoff Hadjiilieva and her colleagues noted a jump in activity within the hippocampus, a key component of the default mode network that is involved in not only memory but also learning and spatial navigation. They might have predicted this location but not the timing. To their surprise, the leap in hippocampal activity preceded the arrival of the thought in the meditator’s consciousness by nearly four seconds – an epoch in brain time, and far longer than it takes for a sensory impression to cross the threshold of our awareness.

“Something is going on prior to awareness,” Christoff Hadjiilieva said, but she’s not sure exactly what it is or why it takes so long. This finding indicates that a spontaneous thought must undergo some sort of complicated unconscious processing before finding (or forcing) its way into the stream of consciousness.

The wrinkle in mental time that Christoff Hadjiilieva has identified remains a mystery, and a highly suggestive one. I’m reminded of James’s account of our peculiar semiconsciousness of missing words. For Christoff Hadjiilieva, the mystery she’s uncovered points to what she regards as the “really hard problem of consciousness” – how the contents of the unconscious form into thoughts that sometimes find their way into our awareness, and sometimes don’t.

I asked Christoff Hadjiilieva why the unconscious receives so little scientific attention. The difficulty of studying it is part of the answer, but she suggested that there is also the question of scientific legitimacy. In the late 19th century, the nascent field of psychology was struggling for acceptance as a science. “To attain legitimacy, the field militantly defended the idea that the mind and consciousness were the same,” Christoff Hadjiilieva said. “But this was a Faustian bargain. Legitimacy meant having to define the mind in a way that guarantees you’ll never understand it.”

As for the orphaned unconscious, psychology left it to psychiatry, where figures such as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung took over the exploration and mapping of its territory. Psychiatry turned what might have been an experimental science into a therapeutic movement. Christoff Hadjiilieva is seeking to reverse that history and return the unconscious to the purview of science.

She is particularly sensitive to the latent politics and power dynamics in her field, as well as the unacknowledged assumptions that often determine what gets taken seriously. “The mind is not a neutral territory,” she stressed. “There are vested interests in what we do with our own minds.” She feels that spontaneous thought has been neglected because, compared with, say, reasoning or problem-solving, it doesn’t produce anything.

Capitalism may have little patience for mind-wandering workers, yet spontaneous thought is surely one of the mothers of creativity. The Oxford Handbook of Spontaneous Thought that Christoff Hadjiilieva co-edited includes an illuminating essay that describes the routines of several highly accomplished historical figures – including Darwin, Beethoven and Dalí – who achieved great success despite working a relatively short day (four to five hours) followed by lots of long walks, afternoon naps, loads of unstructured time, and long vacations. It is often not until we leave our desks to wander, whether in mind or body or both, that inspiration strikes.

Spontaneous thought occasionally graces us with insights we regard as special. We moderns tend to attribute the thoughts that arrive unbidden – from “out of the blue” – to somewhere within us, like the unconscious, but in the past, people believed they came from outside us – inspirations from the Muses or the gods. Yet even now, these spontaneous insights or intuitions possess an aura and an authority that ideas delivered by reasoning seldom command. We imbue them with some residue of magic, perhaps because their origin remains something of a mystery. How strange it is that our own thoughts can surprise us!

So which kind of thought, I wanted to know, should we regard as “productive”?

“Building a rich sense of identity is not something that benefits the current system,” Christoff Hadjiilieva said. “Because if you have people leading meaningful lives and integrating their experiences and realising what really matters to them, that’s just not going to work with how this society runs. You’re not going to need as much stuff.”

Christoff Hadjiilieva concedes that “people in survival mode suppress spontaneous thought” – as she once did as a young woman in Soviet era Sofia – in order to focus on the demands of the present. She regards this as a “psychological perishing”, since such people lose their ability to integrate not only conscious and unconscious thought but also their life experiences. Spontaneous thought represents a precious space of mental freedom and self-creation, a space we should work to defend and expand.

This is an edited extract from A World Appears, published by Penguin Books on 24 February. To support the Guardian, order a copy for £21.25 from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1