Like cholesterol clogging up an artery, it took just a couple of years for the quagga mussels to infiltrate the 5km (3-mile) highway of pipes under the Swiss Federal Technology Institute of Lausanne (EPFL). By the time anyone realised what was going on, it was too late. The power of some heat exchangers had dropped by a third, blocked with ground-up shells.

The air conditioning faltered, and buildings that should have been less than 24C in the summer heat couldn’t get below 26 to 27C. The invasive mollusc had infiltrated pipes that suck cold water from a depth of 75 metres (250ft) in Lake Geneva to cool buildings. “It’s an open invasion,” says Mathurin Dupanier, utilities operations manager at EPFL.

But the damage went far beyond keeping classrooms cool. The university’s datacentres need to be chilled, and long-running experiments cannot tolerate temperature fluctuations. “Research is one of the things we do; if it stops, then the school closes,” says Dupanier. The institute is also home to Tokamak – an experimental nuclear fusion facility that looks to create clean energy from the same process that powers the sun. That, too, needs to be cooled – otherwise it will melt.

‘We were in denial’

Quagga mussels are among the planet’s most potent invasive species. They reproduce at astonishing speed: one female quagga produces up to a million egg cells. Some are known to survive for 30 years in the deepest parts of American lakes. They can breed all year round, and spawn in temperatures as low as 5C.

Dupanier’s team were shocked when they discovered the extent of the invasion in 2022. “We had this denial about what was happening,” he says. The quaggas had only been detected in Lake Geneva six years previously and already they had spread like wildfire.

-

Mathurin Dupanier indicates the water cooling systems that were blocked by the invasive quagga mussels. Photographs: Phoebe Weston/the Guardian; École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

The threats to pieces of infrastructure such as Tokamak illustrate the possible scope of their impact. Losing air cooling there will not result in a nuclear explosion, but equipment will go into shutdown. Now, any activity that uses cold water from the depths of the lake is at risk. Drinking water in Geneva and Lausanne is potentially threatened because the pumping and filtration systems are in the quagga zone. The airport – which uses the same water cooling system as the university – has also been hit. “All of them have this issue around the lake; there is no exception,” says Dupanier.

The only way for EPFL and the University of Lausanne to protect their pipes is to build a new closed-loop, quagga-free cooling system. Construction will start in 2027 and should take five years. Dupanier says it will be a race against time to keep precious research going before the quaggas choke their systems any further.

‘It’s a meadow of quaggas’

From a floating research station on Lake Geneva, the lake looks as it always has, with snow-capped mountains tumbling into its dark waters. Over the past decade, however, ecologists know this lake has changed profoundly. “The surface is just a tiny part of the 300 metres below us,” says Bastiaan Ibelings, a professor in ecology at the University of Geneva.

-

Bastiaan Ibelings, professor of microbial ecology at the University of Geneva

-

A chain hauled from beneath Lake Geneva is covered in invasive quagga mussels. Photographs: Jordi Ruiz Cirera/the Guardian

To illustrate the extent of the changes, technicians pull a chain up from the depths. It is encrusted in quagga mussels, like diamonds on gaudy costume jewellery. The base of the food chain that feeds this entire ecosystem has completely changed: snails, shrimps and native mussels that you might have found previously are nowhere to be seen. Even after 100 metres of chain, quaggas are still being hauled out of the water.

“It is too late for this lake,” says Ibelings. “It’s like a meadow of quaggas down there. Every spot is taken. Instead of seeing sand you see quagga mussels.”

In Lake Geneva the molluscs have reached a record-breaking depth of 250 metres – a pitch-dark environment where there is almost no oxygen, home to scant life other than microbes. Their ability to survive where other species can’t, means they grow uncontrollably in Alpine lakes.

For a long time, the invasion was not very visible to the public, says Ibelings, but now people are noticing something is not right. Dead mussels wash up on beaches, and people can’t walk barefoot because they cut themselves. Recreational boaters have to scrape them off their craft every few months. Crayfish are covered in mussels and dying because they can’t move.

100% of samples

Quaggas originate from the Ponto-Caspian region of the Black Sea and were spread around the world via shipping routes. They invaded the US’s Great Lakes in 1989 and are now the dominant life form, making up more than 99% of all invertebrate biomass in some lakes.

In the US, they have driven a collapse in the region’s fish populations, with lawmakers warning they will need $500m (£375m) in federal funding to address the issue. Great Lake shipwrecks – preserved in pristine condition for more than 100 years – are now coated in quaggas.

This week, they were detected in Northern Ireland for the first time, with the country’s environment minister, Andrew Muir, warning that “increased vigilance and surveillance” was critical.

-

Quagga mussels cover the wreck of Kyle Spangler in Thunder Bay national marine sanctuary on Lake Huron in Michigan, US. Photograph: Joseph Hoyt/NOAA

The mussels were first detected in Switzerland in 2014. The highest density was found in Lake Geneva, with an average of 4,000 quagga mussels a square metre across the whole lake. In some places there were more than 35,000 a square metre. In 2022, researchers found 98.9% of samples were quagga mussels, and in a 2024 survey, they exclusively scooped up quagga mussels – nothing else. “Quaggas were 100% of samples,” says Salomé Boudet, a PhD student at the University of Geneva, who led the study. Mussel biomass in Lake Geneva is now comparable to what has been found in the Great Lakes, researchers say.

Globally, invasive species such as these are one of the five main drivers of biodiversity decline. The ecological knock-on effects in Swiss lakes will play out in the coming years.

‘Going back is a fairytale’

Each mussel can filter up to two litres of water a day, feeding primarily on phytoplankton, which forms the basis of the lake food chain. Tiny creatures such as water flea feed on phytoplankton, and then fish feed on the water flea. When the base of the chain disappears, it has cascading impacts on the entire food web, and potentially severe impacts on the livelihood of the 120 professional fishers working on Lake Geneva.

-

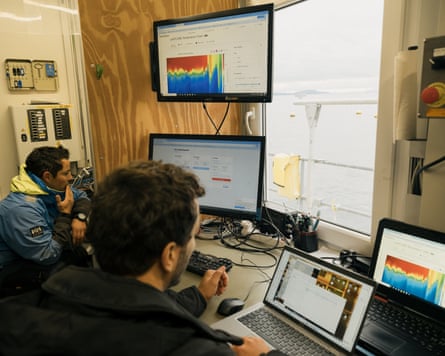

Data is gathered from a floating research laboratory on Lake Geneva

-

Scientists are working to track changes in the lake and model ecological processes. Photographs: Jordi Ruiz Cirera/the Guardian

The filtering activity of quaggas also results in the water being clearer, which means light penetrates deeper. Like climate breakdown, this can lead to warmer water reaching deeper, with knock-on effects including an increase in toxic blue-green algal blooms. Previously, cold air from the atmosphere created lake currents, resulting in the mixing of water, but this hasn’t happened since 2012.

Once quagga mussels are in a lake there is nothing you can do, other than stop them colonising other lakes by cleaning boats and fishing equipment.

After thousands of years of stability, Lake Geneva is undergoing a period of huge and irreversible change in the space of just a decade. In the US lakes, there are no signs of quagga populations falling after 30 years of colonisation.

Ibelings says: “Going back is a fairytale, because of quagga mussels and climate change. We cannot control either, and I don’t think they will go away. We need to understand what they are doing to the lake.”

In the future it is possible that nature will evolve, and some fish may adapt to eat quagga mussels, but ecologists say Lake Geneva will never be the same. “We need to accept at some point, whatever is there – this is a different lake, now,” says Ibelings.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage

2 months ago

48

2 months ago

48