As the members of the Catholic organisation wrapped up their speech with an appeal for forgiveness, the auditorium in Madrid exploded in rage. For decades, many in the audience had grappled with the scars left by their time in Catholic-run institutions; now they were on their feet chanting: “Truth, justice and reparations” and – laying bare their rejection of any apology – “Neither forget, nor forgive”.

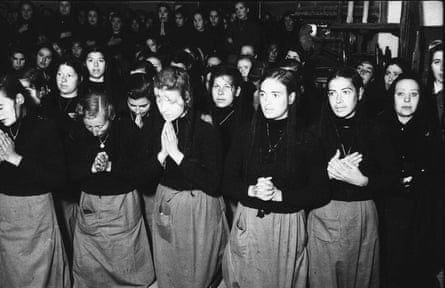

It was an unprecedented response to an unprecedented moment in Spain, hinting at the deep fissures that linger over one of the longest-running and least-known institutions of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship: the Catholic-run centres that incarcerated thousands of women and girls as young as eight, subjecting them to barbaric punishments, forced labour and religious indoctrination.

The centres operated under the direction of the Women’s Protection Board, a state-run institution revived in 1941 and helmed by Franco’s wife, Carmen Polo. They aimed to rehabilitate “fallen women”, aged 15 to 25, as well as others deemed to be at risk of deviating from the narrow path marked out for women during the dictatorship.

Survivors, however, describe a reality that was far more brutal. “It was the greatest atrocity Spain has committed against women,” said Consuelo García del Cid, who was drugged by a doctor at her home in Barcelona and taken to a centre in Madrid at the age of 16.

In her case, her family had branded her rebellious after she attended rallies against the dictatorship. “In Franco’s Spain, a fallen woman could be anyone. If you were poor, an orphan, if your family faced hardship, if you were a bad student or wore a miniskirt or kissed your boyfriend in a cinema or danced too close – anything was enough.”

Many women were hauled into the centres in handcuffs after being singled out by priests, neighbours or relatives. Others were reported by state employees known as the “guardians of morality”, who patrolled the streets and venues such as movie theatres, swimming pools and gardens, calling the police any time they spotted a woman they believed to be in moral danger, said García del Cid, who has written five books on the centres.

“It was a covert prison system for minors,” she said. “You couldn’t go out, your mail was censored, visits were supervised by a nun. They had us working all the time, scrubbing and praying. We worked for free; sewing, embroidery, knitting, doll-making. We weren’t allowed to speak freely to each other, we couldn’t have friends. They were watching us all the time.”

The centres, which are believed to have held more than 40,000 young women and girls at their peak, were not closed until 1985 – 10 years after Franco’s death.

Amid pressure from survivors and after more than a year investigating their claims, Confer, a Catholic body representing more than 400 congregations, including many with ties to the centres, said it was ready to seek forgiveness for what had happened.

The ceremony, the first of its kind in Spain, got under way on Monday with the chair of Confer explaining that the organisation was ready to break its decades of silence over what had happened.

“We acknowledge this page in our history,” said Jesús Díaz Sariego. “This is an exercise in moral and historical responsibility, an opportunity to acknowledge what we did not do well in the past and express our empathy and deep sorrow to all these women.”

He contextualised the centres within the narrow norms of a dictatorship that had rolled back the rights of women, requiring them to obtain the permission of male guardians to work, travel or open a bank account. It was a “time of severe educational, social, political, and religious restrictions”, he said.

His remarks were followed by an audio compilation of survivors’ testimonies. Some spoke of wrestling with abuse by nuns when they were just eight or 11 years old, others told of punishments that ranged from rubbing nettles on the vulvas of those who wet the bed, to forcing people to eat their own vomit or draw crosses on the floor with their tongues.

“In the name of what God was this done?” one woman asked. “What kind of religious women could carry out such evil against children who had committed no crime?”

Most remembered the centres as places of beatings, verbal abuse, gnawing hunger and cold. Some spoke of the decades it had taken them to learn to live with their experience, while others hinted at those who had been consumed by the trauma and had turned to drugs or suicide.

after newsletter promotion

By the time the three members of Confer stood up to ask formally for forgiveness, emotions were high. As many survivors, flanked by their families and historical memory campaigners, began chanting, brandishing signs that read “No” and raising their voices as organisers tried to drown them out with music, Confer suspended the event.

Survivors were swift to explain their reaction. “It’s not a genuine apology,” said Dolores Gómez, who was sent to a centre at 13 after she told a psychiatrist her father was sexually abusing her. “This is just a facelift.”

The audio that had played during the ceremony had been edited to omit some claims, including those of women who said they had been pressured to give up their babies for adoption, said Gómez. “They’re not asking forgiveness for all that happened, they’re only asking forgiveness for the actions they are willing to recognise.”

After a few months at the centre, Gómez escaped, choosing to return home and risk her father’s abuse over the nuns’ treatment. At 15 she was sent back after her father raped her, leaving her pregnant. The following year, the nuns granted her father permission to take her out during the Easter holidays, allowing him to again rape and impregnate her. It took Gómez years to track down her children and start the painstaking process of building a relationship with them.

While Confer had been clear in asking the women for forgiveness, there was little sign they had delved into their own consciences and how they had allowed this to happen, said Paca Blanco, whose conservative family institutionalised her at 15 after she returned home from a party.

“They need to ask forgiveness of themselves first,” she said. “How do you apologise to teenage girls that you have tortured, mistreated, disrespected and exploited for labour? You’ve stolen their babies. How do you apologise for that?”

Some survivors, however, disagreed. “I would have liked if we could have made it to the end of the event,” said Mariaje López who was eight when she was sent to live with the nuns. “I think so many women needed to hear this apology to understand that the shame is on the other side. Particularly the tens of thousands of women who remain silent and ashamed over what happened.”

What was clear to everyone, however, was that Monday’s apology – accepted or not – was the tepid beginning of a much longer journey. “This is one step forward in the ongoing battle,” said García del Cid.

She had requested a meeting with Spain’s minister of justice, hoping to have survivors formally recognised as victims of the dictatorship and potentially paving the way for a response along the lines of Ireland’s 2013 apology and reparations for the abuses that took place in its Magdalene Laundries. In Spain, there has been little fallout from the role that church and state played in operating the centres; the congregations had never faced any kind of reckoning, with many of them continuing to receive public funding, said García del Cid.

Hovering over all of this was the question of just how these centres were able to continue operating after the death of Franco, leaving young women incarcerated even as Spain transitioned to a democracy. “They forgot about us, we didn’t matter,” said García del Cid. “They need to explain a lot to us. Democracy owes us 10 years of life.”

2 months ago

38

2 months ago

38