The sales patterns for classic novels are normally a fairly predictable business. “Every year it’s the same authors,” says Jessica Harrison, publishing director for Penguin Classics UK. “Austen is always at the very top, and then all the school ones: Orwell, An Inspector Calls, Of Mice and Men, Jane Eyre.”

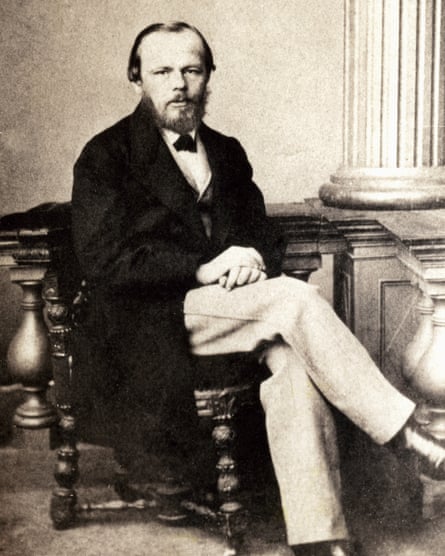

But last year it was different. Penguin’s bestselling classic by far was a little-known novella by Fyodor Dostoevsky. White Nights sold more than 100,000 copies in the UK in 2024. It is an angsty story of impossible love, run through with characteristic Dostoevskian gloom. A young man and woman meet on a bridge in St Petersburg on consecutive nights: his love for her is unrequited; she is despairing because the man she really loves has ghosted her. The pleasure the young man takes in her company is shadowed by the knowledge that it can never be permanent.

This year has seen another surprise hit. Turkish author Sabahattin Ali’s 1943 novel Madonna in a Fur Coat, first published by Penguin in 2016, has rocketed this year, selling almost 30,000 copies in the UK and outstripping even Pride and Prejudice. It’s another anguished story of frustrated love, this time set in Berlin, where a young Turkish man falls in love with a woman in a painting. What follows is a spiral of fear, guilt and regret.

The stories, ripe with what Harrison calls “existential dread” and – no spoilers – with little prospect of a happy ending, are not obvious bestseller material. So what has happened? One answer is that our reading reflects our times, and we live in turbulent times. Madonna in a Fur Coat is a tale of passion set against the economic turmoil of the 1920s: why would it not appeal to readers living through the economic turmoil of the 2020s?

These books were, says Harrison, “written in times of change or moments of flux. They’re about, how do you live your life when the world around you is changing, and the things you thought you knew are no longer true?” In White Nights, each of the near-lovers is dealing with the loss of someone they loved – or thought they did.

There are of course other authors with similar qualities, so what drew these particular books to such a wide readership? The answer lies in the medium as well as the message. Dostoevsky and Ali have both enjoyed a frenzy of attention on social media, and TikTok in particular.

According to TikTok users, White Nights is “the most relatable love story I’ve ever read”, a book that “will follow you for the rest of your life”. Madonna is “devastating”, it’s “not just a book … it’s a window to my soul”.

And behind all this attention stands one man: Jack Edwards, the UK’s most popular bookish social media star. Edwards, who terms himself “the internet’s resident librarian”, has more than 750,000 followers on TikTok and 1.5 million on YouTube. What he thinks, counts.

Edwards’s TikTok video in January 2024 raving about White Nights has had 380,000 likes. What appealed to him about the book? “I couldn’t believe how modern it felt, despite being written in 1848,” he says. The novella feels perennial, with “its themes of wanting to love and be loved”.

Similarly, reading Madonna in a Fur Coat – which Edwards discovered during a series picking out a book from every country in the world – he fell instantly in love with “the yearning and heartbreak of the central character”.

The fact that these books are, in some senses, pretty bleak does not diminish their appeal. It may even enhance it. “I think of that James Baldwin quote,” Edwards adds: “‘You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.’ That’s how it feels to find yourself in these pages. Ultimately, it makes us feel less alone.”

The love for these books fits with TikTok’s youth-skewed user base, Harrison says. “It’s about the heightened emotions and the yearning that is such a key feeling when you’re a teenager and a teenager online. They’re [also] about loneliness, both of those books. So it’s obvious that they speak to an online audience particularly.” And they are not difficult books in literary terms: their turmoil is, as Harrison puts it, “couched within an accessible and approachable love story”.

after newsletter promotion

There are other recent successes that are altogether more severe. Japanese author Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human, the dark story of a man who hides his misery beneath a jocular facade – published shortly after Dazai’s suicide – last year became a bestseller in the UK despite being available only in an imported US edition. The “extravagantly tortured” Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen, who died in 1976, has become hot property since the 2019 republication of her trilogy of memoirs, Childhood, Youth and Dependency: books as bleak as they are beautiful.

Last month, Penguin introduced a new series of classics in translation, with a relaunch of the Penguin International Writers series that previously ran through the 1980s and 90s. In the first set is Ágota Kristóf’s I Don’t Care, a collection of stories from the Hungarian author of the brutally stark masterpiece The Notebook.

Kristóf’s stories compress lives into a few pages – “The man was watching his life desert him” is a typical opening – and offer few consolations for the reader. In one story, the narrator feeds a group of unsuspecting neighbours their pet cat; in another, the narrator looks ahead with pleasure and even excitement to the last years of her life.

These stories – “stark fables of timeless relevance”, in the words of Denise Rose Hansen, the Penguin editor behind the relaunch – might be catnip for the readership that has developed a taste for existential angst from White Nights or Madonna in a Fur Coat. (The fact that I Don’t Care is produced in a plain-cover format, reminiscent of the ever-cool Fitzcarraldo Editions, is probably not a coincidence.) But Kristóf’s stories are, says Hansen, also “spikily funny”: “it’s surprising to me that she has remained a secret in Britain while being so influential in neighbouring countries”.

Occasionally, a surprise bestseller takes on a different type of darkness. When Penguin celebrated its 90th anniversary earlier this year by reissuing selected classic titles under the collective brand Penguin Archive, the immediate bestseller was not Orwell or Fitzgerald but Bram Stoker’s The Burial of the Rats, a collection of stories that feature horror both existential (madness) and physical (man-eating rats).

The appetite for existential literature, then, shows no signs of abating – as long as readers continue to find that darkness in society is best illuminated by darkness in art.

2 months ago

59

2 months ago

59