This spring, something strange started happening at the Fillmore Bakery in San Francisco, which specializes in old-school European desserts.

Excited customers kept asking the bakery’s co-owner, Elena Basegio, “Did you see about the princess cake online?”

The dome-shaped Swedish layer cake, topped with a smooth layer of green marizipan, had suddenly gone viral, increasing sales of the bakery’s already-bestselling cake.

After nearly a century of demure European popularity, “prinsesstårta” suddenly seemed to be everywhere: on menus at hip restaurants in Los Angeles and New York, trending on TikTok, even inspiring candle scents at boutique lifestyle brands.

The Swedish consulate in San Francisco confirmed the phenomenon, telling the Guardian that the trend appears to be driven by innovative American pastry chefs such as Hannah Ziskin, whose Echo Park pizza parlor has offered up a sleek redesign of the palatial pastry, as well as by online food influencers, some of whom have offered American bakers more “accessible” versions of the elaborate dessert.

The reinvention of one of Sweden’s most cherished desserts as a trendy indulgence might seem like just another retro fad, like the renewed popularity of martinis or caviar. But as a product of the European country with the highest rating for gender equality between men and women, princess cake is more subversive than its smooth marzipan surface might suggest.

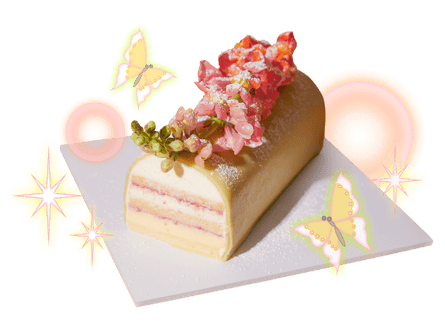

This is, after all, a cake so difficult to construct that it served as an early technical challenge on the Great British Bake-Off: its wrinkle-free marzipan dome is a fiendish feat of kitchen engineering. Americans are also leaning into the dessert’s more seductive qualities: to state the obvious, this is a breast-shaped cake topped with a rosy marzipan nipple. Its green coating might conjure up a buxom extraterrestrial, but that doesn’t really change the fundamental impression: this cake is very, very sexy.

Training the princesses

When Ziskin, the Los Angeles pastry chef, started serving slices of princess cake at her restaurant Quarter Sheets, many of her patrons were so unfamiliar with the dessert that they asked if she had created and named it herself.

In fact, the invention of the cake is credited to a prominent Swedish home economics teacher named Jenny Åkerström, whose students at her “renowned school of cookery” in the early 1900s included the princesses of Sweden. Åkerström turned this experience into the 1929 Prinsessornas Kokbook, a popular collection of recipes dedicated to her three royal pupils. “These Swedish recipes of good taste are recommended by their majesties Margaret, Matha and Astrid to her majesty the American housewife,” a 1936 English translation of the cookbook promised.

Åkerström’s recipe for a marzipan-covered “gröntårta”, or green tart, is included in one of the later editions of her cookbook.

Princess cake went on to become the iconic Swedish dessert, one served at birthdays, graduations and office parties. It’s traditional to fight over who gets to eat the marzipan rose perched on top of the dome. Sweden’s tourism bureau estimates that half a million “Prinsesstårtor” are sold in the country each year. Since 2004, there’s even been a “princess cake week” held each September, during which some of the proceeds from cake sales are donated to a royal charity.

For Emelie Kihlstrom, a restaurant owner raised in Sweden and now living in New York, princess cake was so ubiquitous it felt a bit stodgy. “I wasn’t a huge fan, personally,” she said. “We have been eating it the same way always – there was never any variation.”

For her new French-Scandinavian restaurant Hildur, in Brooklyn, Kihlstrom decided to reinvent the classic dessert. Together with Simon Richtman, a chef who once worked for the Swedish consulate in New York, she developed a single-serving pink version of the cake, with queen’s jam – a mixture of blueberries and raspberries – instead of the raspberry jam, and a lighter diplomat cream in place of the traditional pastry cream filling.

At her restaurant, “It’s on every table,” Kihlstrom said. “It’s funny how it’s just become this phenomenon.”

Nearby in Brooklyn, the owners of BonBon, the TikTok-famous Swedish “candy salad” shop, have now opened Ferrane, a Swedish bakery which offers their own twist on princess cake. Their cocktail-glass mini cakes were inspired by the Swedish restaurant Sturehof, which now serves a tiny princess cake in a rounded coupe glass, Kihlstrom said.

Sturehof’s Yohanna Blomgren debuted their reinvented princess cake in Stockholm last September, and a spokesperson for the restaurant said that the classic dessert was having a “resurgence” in Sweden, as well as in the US.

The cocktail glass version has taken off far beyond the Swedish restaurant’s expectations. “Many guests visit us specifically to try it – some even mentioning they’ve travelled across the country just for the cake,” the Sturehof spokesperson wrote.

In Los Angeles, Ziskin has also tweaked the traditional recipe, making her chiffon cake with olive oil, to give it a flavor that’s “a little more savory, a little more grassy”, adding mascarpone to the whipped cream, for a “savory note”, and making both her “super tart” raspberry jam and her marzipan from scratch.

“It’s really light – the layers are light,” Ziskin said. “It’s something you can finish.”

Instead of forming the cakes into tricky-to-construct domes, Ziskin makes her princess cakes in long rounded logs. Slices of the cake are so popular that they sell out almost every night: “People will email in advance and ask us to hold slices for their dinner,” she said.

A Bon Appetit video of Ziskin making her “homage” to the Swedish national cake went viral last fall, garnering more than 1m views and sparking heated pushback in the comments over the use of mascarpone, the correct shade of green for the marzipan – and the missing marzipan rose. (Ziskin garnishes logs of her cake, which sell for $85 each, with real flowers.) “Why do Americans have to ruin everything,” one TikTok commenter asked. “If you’re doing something, do it properly.”

Then, in April, British baker Nicola Lamb published a “simplified” princess cake recipe in the New York Times – one made upside down in a bowl, to help with the difficulty of creating the dome shape. The Food Network’s Molly Yeh produced an even-easier square pan version.

By early May, the food site Eater had declared: “The Princess Cake Gets Its Princess Moment.”

For longtime American fans of princess cake, this fanfare of discovery has been a little befuddling. MacKenzie Chung Fegan, the food critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, credited the “great mainstreaming of princess cake” to New Yorkers belatedly encountering a dessert that was already popular elsewhere.

“I lived in New York, a city of 8 million people and nearly as many bakeries, for 20 years and never spotted a princess cake in the wild,” she wrote. Growing up in California’s Bay Area, by contrast, princess cake had been a familiar treat available at many local European bakeries.

Ikea, the Swedish home furnishings superstore, has long offered its own princess cake, the “KAFFEREP Cream Cake,” in its frozen food aisle, and has also sold the cake in Ikea restaurants in the US since 2019. The Ikea cake comes in a tiny, single-size version, with pink marzipan instead of green, and has some very enthusiastic American fans on Reddit.

Ziskin, the Los Angeles pastry chef, said she grew up eating supermarket princess cake from the Viktor Benes bakery at Gelson’s, a southern California grocery.

“I’ve literally had princess cake for my birthday since I was five years old,” Ziskin said. “It was always part of my life.”

‘Real men eat princess cake’

For some Americans, the sheer femininity of princess cake can cause some anxiety.

“People come in and say, ‘I’d really like to give this cake to my husband, but is there a way to make it more masculine?” said Basegio, the owner of the Fillmore Bakery in San Francisco. “They’ll ask us to take the rose off the top, so it’s just green... We’ve been asked to make it blue, which we don’t do. It’s just cake.”

These concerns are “frequent” and they always come from women buying the cake for men, Basegio said, even though, “men, specifically, would be the demographic that love princess cake cake most”.

One of Basegio’s ex-boyfriends once made her a shirt that read, “Real men eat princess cake,” illustrated with a tattooed arm holding up the cake.

While princess cake might seem like a recipe that would be popular with trad wife influencers, that does not appear to be the case. I asked Ziskin about this. While not wanting to sound “snooty”, Ziskin said, she thought it might be a skills issue.

“It’s a difficult thing to make well and present well, without your marzipan cracking,” Ziskin said. “It’s kind of more in the world of professional baking … there’s something that’s a little inaccessible about it.”

If you make a mistake while frosting a cake with buttercream, “you can wipe it and do it again,” Ziskin said. “You can’t take back the final placement of the marzipan.”

There are online debates over where to find the best princess cake in the United States. Quarter Sheets is among the contenders: Ziskin said that Lost Larson in Chicago, Sant Ambroeus in New York, and Copenhagen Pastry in Los Angeles are also frequently mentioned.

As princess cake grows in popularity, Ziskin said, she’s excited to see people continue to experiment with the flavors of the traditional cake. And, she added, “I’m interested to see how certain countries react to that.”

3 months ago

64

3 months ago

64