‘We got the bus and went down to Sheffield to visit the supporters who were in hospital,” Kenny Dalglish says as he remembers how he spent the Monday after the tragedy of Hillsborough in April 1989. “All the players were there so we split up and they walked into different wards to see people. We were trying to give them a wee bit of confidence or belief of anything that could help them. And there was a family around a young boy’s bed and he was unconscious.”

Sean Luckett was 20 years old and one of the thousands of fervent Liverpool supporters who had travelled to Hillsborough to support the team who Dalglish managed and had played for with such sublime talent since arriving from Celtic in 1977. Ninety-seven Liverpool fans eventually lost their lives after the unbearable crush during the club’s FA Cup semi-final against Nottingham Forest.

Luckett had been in a coma for two days when Dalglish stood at his bedside at the Royal Hallamshire hospital. With the Luckett family gathered around him, Dalglish said: “Hi there, wee man. Come on, you’ll be all right. We love your support.”

Thirty-six years later, on a rainy Thursday afternoon in London, Dalglish shakes his head in wonder at the memory of what happened next. “We were walking away and there was a scream. What’s happened here? I turned round and the wee man was sitting up. Unbelievable.”

David Edbrooke, a consultant anaesthetist, was quoted in the Times the following day, 18 April 1989, as he described the apparent miracle. “I have never seen anything like it,” Edbrooke said. “[Luckett] opened his eyes and whispered: ‘Kenny Dalglish.’”

The Liverpool manager said: “Well done, wee man,” with his familiar wry smile, before moving on to the next ward.

Such vivid moments, and monuments of social and football history, light up Asif Kapadia’s moving new film on Dalglish. The Oscar-winning director, who made an unforgettable trilogy of documentaries about Ayrton Senna, Diego Maradona and Amy Winehouse, has turned his lifelong love of Liverpool into a compelling portrait of Dalglish.

From a childhood in Glasgow, to his youthful brilliance at Celtic and his magisterial playing career at Liverpool where he won multiple league titles and European Cups, to his compassion as their manager after Hillsborough, the film also captures the toll that death and institutionalised deceit took on Dalglish.

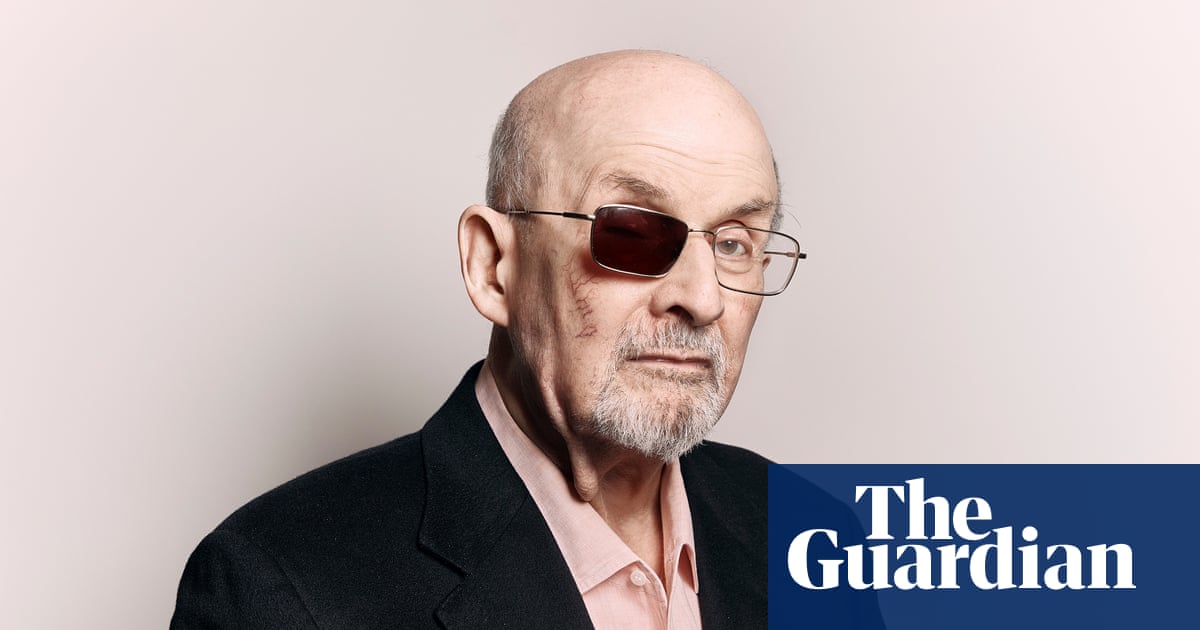

The 74-year-old pauses when I ask what he thought as he watched the documentary. “I’m just emotional,” Dalglish says quietly.

Kapadia agrees. “When I make a film I sometimes don’t know what it’s about until afterwards. What’s been really interesting about this film is that it’s very emotional. There is the emotion of the people who were there and the emotion of people who are watching. It’s really interesting how people who don’t know anything about Liverpool, or don’t even watch football, are affected. Kenny and Marina [Dalglish’s wife], and all those around them, are just good people. It’s important – particularly now when so many awful people are in positions of power – to tell a story about good people who care about others.”

Dalglish says simply: “You’re supposed to help.”

Returning to the film, Dalglish adds: “Some people have said: ‘Oh, I’ve never seen that footage before. [Former Celtic manager] Jock Stein on the pitch and a wee kid of 17.’ He’s coaching us. Big Jock was a huge influence on me, and a good fellow.”

Kapadia leans forward: “I really love it if you can tell a story about Kenny Dalglish via Jock Stein, Bill Shankly, Bob Paisley and the players. Paul McCartney is in it. It’s full of cultural and sporting icons and moments of history. My kids didn’t know this. They hadn’t seen Kenny play. So I wanted to tell a story about a period before the Premier League, before the Champions League, before history was rewritten and started from zero. It’s all these amazing people, and amazing football, that I wanted to show.”

A deadpan Dalglish says: “All that low blocking and high pressing.”

Amid the laughter Kapadia exclaims: “And xG! The language of football was rewritten and I’m like, let’s go back to Roy of the Rovers, Panini, and bring it forward from there.”

“What does it mean, xG?” Dalglish asks.

“Expected goals,” Kapadia replies, “but I’ve no idea how they calculate that. The chance that Mo [Salah] had was an xG of 0.6 and if he’d passed it to [Florian] Wirtz that would’ve been an xG of 0.8.”

“He should have passed it,” Dalglish quips.

“Kenny, you’ve won more trophies than anyone can count, scored the winning goal in a Champions League final, winning goal to clinch the league, managed the team that won the Double, and you don’t even know what xG is.”

“I left school at 15.”

“They’ve embedded things to make you and I go: ‘What does that mean?’” the 53-year-old Kapadia laments.

“New technology,” Dalglish replies.

“Yes,” Kapadia sighs. “None of us can tell what a handball is any more. What’s going on?”

“Naebody knows.”

Beyond Dalglish’s familiar dry wit lingers terrible pain and anger. There is a scene in Kapadia’s film where Dalglish struggles to choke back the tears as he remembers taking his eldest children Paul and Kelly on to the Kop a few days after Hillsborough. The famous old terrace was silent and covered in a sea of flowers and scarves.

“It told me how close the supporters were to each other and the football team,” Dalglish says. “You saw little messages left by supporters for guys they must have stood beside for every home game. Someone left an orange. They must have shared an orange every game. It was hard for Kelly and Paul to take when they were walking through. It was hard for me as well.”

Paul and Kelly had both been at Hillsborough and it took almost 20 minutes before Dalglish knew his son was safe. Kapadia’s film includes a distressing photograph which captures the horror on Dalglish’s face as people die around him. “It was scandalous,” Dalglish says now. “Disgraceful.”

The FA insisted that Liverpool had to play their abandoned semi-final against Forest just three weeks later. “It was heartless. To say that you’re going to be thrown out of the competition? It was absolutely scandalous.”

Dalglish details the many mistakes the FA and the police made in herding the Liverpool fans into the crammed pens at the Leppings Lane end and says: “It was preventable. And they never took any responsibility whatsoever. Never. The people that needed the greatest care never got it from the FA, not from anybody outside.”

Is that why Dalglish showed such compassion for the families for decades? “I did it because I thought it was the right thing to do. I was just supporting people who had suffered.”

The Sun newspaper lied systematically about Liverpool supporters, claiming they were drunk and violent and had caused the disaster. Dalglish was telephoned by the Sun’s editor Kelvin MacKenzie, who asked him what they could do to end the city’s boycott of his newspaper. “I said: ‘You know the best thing you can do? Just put We Lied in the headline.’ He said he can’t do that. So I says: ‘I cannae help you.’ Put the phone down.”

It took another 27 years before an inquest in 2016 determined that all those who lost their lives were unlawfully killed by a catalogue of failings by the police and ambulance services. But as Dalglish says now of the families of the victims: “I don’t think they’ll ever get closure. History doesn’t give you closure, does it? I don’t think it’s possible.”

Dalglish was scarred by all he witnessed but he says: “I don’t think I looked at myself and thought about the ramifications. I did it because it’s what you’re supposed to do. Me and Marina were brought up the same way, Glaswegian, where it’s what’s in your heart that counts.”

All these years later it was touching to see, last Sunday at Anfield, Dalglish and Alex Ferguson, another great old Glaswegian, chatting away before and after Liverpool’s surprise defeat by Manchester United. Their fierce rivalry melted away.

“Aye!” Dalglish says with a grin. “Of course I gave him chocolates. He enjoyed them as well. He was like a wee kid going to school. Behave yourself or you’re not having any chocolate buttons. He was in good form, before the game as well.”

Liverpool suffered their fourth successive loss that afternoon and I ask Dalglish if he was worried three nights later when they went 1-0 down to Eintracht Frankfurt before scoring five unanswered goals. “It was never in doubt.”

The head coach Arne Slot did an incredible job last season, winning the league at a canter while being wise enough not to disrupt the team that Jürgen Klopp had built. This summer Slot spent £450m, including £125m on Alexander Isak while introducing other gifted attacking players in Wirtz and Hugo Ekitiké. “Amazing, isn’t it?” Dalglish says. “Arne had a great season last season. And all of a sudden, within two months, everything needs revisiting. I’m not talking about him, I’m talking about people’s opinions.

“He only made two signings last year. [Giorgi] Mamardashvili, the [reserve] goalkeeper, and [Federico] Chiesa. This year he spends a few quid and after two months they’re saying he should do this, he should do that. But if he hadn’t bought anybody, they’d say: ‘Why didn’t he buy?’ The only way he can win is to win games. And that was a great result [in Frankfurt].”

There is no mini-crisis for Liverpool in Dalglish’s mind. He is back to his sphinx-like best when I ask if Liverpool will win the league again. “I’m no clairvoyant. But we’ll have a go.”

He describes Wirtz as a “very clever” footballer and picks out Salah as the player he has enjoyed watching most in recent years. “The goals Salah scored, and the assists he made, were very entertaining and exciting. One or two always stick out when the team’s successful. But, in a team sport, everybody’s important.”

Kapadia is almost as passionate about Liverpool as Dalglish. “My family are all Arsenal fans,” he says. “We’re north Londoners but my best friend was this Turkish boy I grew up with in Stamford Hill. He liked Kenny Dalglish and Liverpool, and I was like, ‘OK, I’ll copy you.’ How life-changing that is when you’re four, on a tricycle, playing in the street, and trying to write your name on a ball from Woolworths.”

Dalglish smiles in understanding and Kapadia says: “When we showed the film in Italy a journalist said she really noticed the word that comes up again and again. People. It’s for the people. It’s about people. That’s what you say, Kenny, and what you do. You do everything for the people.”

Kapadia turns to me. “It’s nice to have good human beings who stand up for those who don’t have a voice, who don’t have any power. When everyone seems against them, someone needs to step up. Kenny did that again and again. So I’m glad I made the film. We have this moment while Kenny’s here and feels it. We’re not waiting till after he’s gone to tell him how much we all love him.”

Kenny Dalglish will be in cinemas 29-30 October and on Amazon Prime from 4 November

3 months ago

73

3 months ago

73