Every February, members of the Iranian diaspora descend on an abandoned plot of land in an unremarkable street in the French town of Neauphle-le-Château, a 90-minute drive west of Paris.

On the nominated Sunday, a marquee is hastily thrown up and framed photographs of the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini hung on the canvas. Green baize is laid on the muddy garden path between posts painted with equal bands of green, white and red, the colours of the Islamic republic’s flag.

They come to remember the supreme leader who, in a chapter of history little known outside France, spent four months in the town in the late 1970s before his triumphant return to Tehran as the leader of the Islamic revolution.

The fact this is commemorated every year in a small town in Île-de-France evokes a deep grievance among local people, and particularly this year. That their home has become synonymous with a regime in Tehran accused of killing thousands, some say tens of thousands, in a continuing crackdown, feels, they say, like a betrayal. Rather than remembering, they would rather forget.

“People prefer not to speak of it. It’s a moment in history that has nothing to do with us,” says Pascal Pagand, who owns the Café des Sports in the town square, the hub of local life.

“I know it still annoys people. They don’t understand why he was given sanctuary here … The town wasn’t asked or consulted. It was imposed; people had no choice. I wasn’t here back then, but those who were here remember it as a difficult time.”

Visitors have been making the annual pilgrimage to Neauphle-le-Château, a 90-minute drive west of Paris, for 47 years. In October 1978, the then French president, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, agreed to allow Khomeini to settle in France after his expulsion from Iraq.

D’Estaing was persuaded that the Shia cleric would be a democratic alternative to the autocratic Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the erratic shah whose regime was in its dying days. The Frenchman also believed Khomenei would reward Paris’s hospitality with lucrative contracts establishing France as a counterweight to US influence in the region.

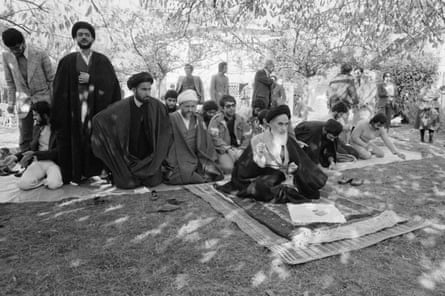

Photographs and newsreel from the time show Khomeini meditating under an apple tree in the garden of 23 Route de Chevreuse. Inside, his acolytes prepared hundreds of cassette recordings of Khomeini urging Iranians to rise up, tapes that were flown to Tehran to be spread secretly across Iran.

Nowadays there is nothing left of the two-storey house that was destroyed many years ago. Locals believe it was “plastiqué” (blown to bits), either by French secret services or by angry Pahlavi supporters after Khomeini left. The force of the explosion cracked the windows of neighbouring homes, they say.

In France, leftwing intellectuals hailed Khomeini as the new Gandhi, among them Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault, who would later regret setting up a Khomeini support committee, ignoring Simone de Beauvoir’s warnings that the radical version of Islam he espoused threatened women’s rights.

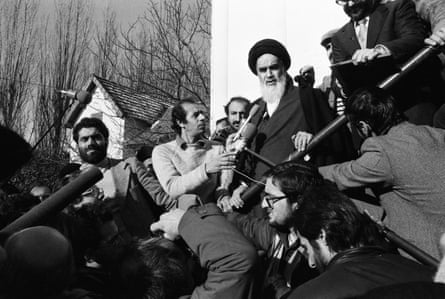

On 1 February 1979, 15 days after Pahlavi fled into exile, Khomeini flew – first-class on Air France courtesy of the French government – to Tehran. He was greeted by ecstatic crowds and within days had established the theocratic dictatorship that has ruled Iran ever since.

In Neauphle-le-Château, what irks locals is the sense that the town is on the map for the wrong reason. Why can it not be remembered for the novelist and playwright Marguerite Duras who lived and wrote there? Why not for Grand Marnier Cordon Rouge, the Cognac and bitter-orange liqueur, created and produced there until, like Khomeini, it moved elsewhere?

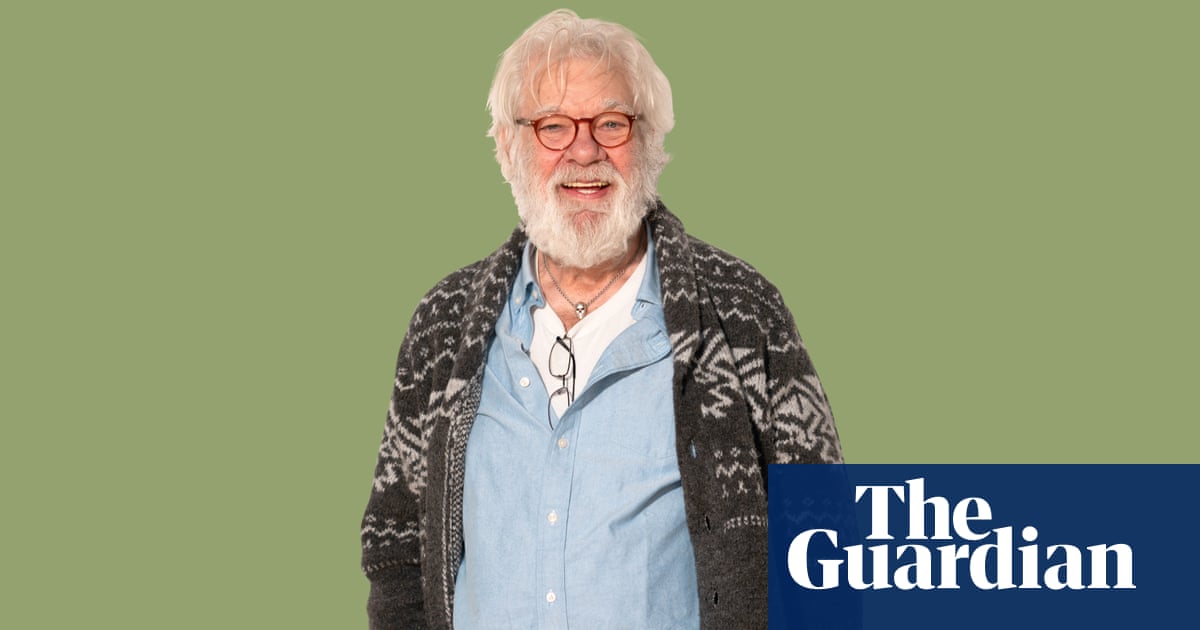

Sitting under a photograph of Duras at a corner table in the Café des Sports, Jean-Claude Cintas, an artist and film-maker, summed up the collective dismay. “Most people here would rather Neauphle-le-Château was known for Marguerite Duras and Grand Marnier,” he said.

Cintas remembers seeing Khomenei on his way to pray and recalls the widespread support for him in France. “At the time, the left was very much for Khomeini and didn’t have a word to say against him,” he said.

“It was only 10 years after May 1968,” he added, referring to the leftwing student-led revolt that almost brought down the French government. “It was an extraordinary era. The shah was basically in the bin and if you were leftwing you were for Khomeini.

“But he was not at all welcome locally. It wasn’t aimed at him personally, because people didn’t know who he was at first; it was because the town was suddenly overrun with journalists and police and it caused chaos.”

Cintas added: “Suddenly every time the town was mentioned, it was in connection with Khomeini. It’s been like it for 47 years now and we feel that’s not what we are about.”

In Tehran, long after Khomenei’s death aged 86 in 1989, Neauphle-le-Château has become part of the city’s geography. The street on which the French embassy sits was changed to rue Neauphle-le-Château.

While most French people over the age of 50 will immediately associate Neauphle-le-Château with Khomeini, the town has been making efforts to bury the memories. Three years ago, during the protests resulting from the death in police custody of Mahsa Amini, who had been arrested three days earlier for allegedly breaching the Islamic dress code for women, a commemorative board at the property on Route de Chevreuse bearing Khomeini’s portrait was vandalised. The town hall ordered its removal and decreed there should be no permanent sign marking his stay.

Elisabeth Sandjivy, the mayor of Neauphle, told French media at the time: “I would like the town of Neauphle to no longer be associated with this part of history that has been imposed on it, because it was the government that gave permission for the ayatollah to stay here.”

French media reported that an official request from Tehran to create a museum on the site had been met with a definitive “non”. Attempts by the Guardian to speak to Sandjivy were unsuccessful.

“Locals will tell you they don’t care about the town’s association with the Ayatollah Khomeini and they don’t want to talk about it, but deep down it still rankles,” said Cintas. “It’s not what we want our town to be remembered for.

“Khomeini spent only four months living on the very outskirts of the town, but his stay has thrown a shadow over the entire place especially with what has happened since.

“There is a sense of betrayal: we gave him sanctuary and instead of democracy this is what he did.”

3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3