In Emilio Peña Delgado’s home, several photos hang on the wall. One shows him standing in front of a statue with his wife and oldest son in the centre of San José and smiling. In another, his two sons sit in front of caricatures from the film Cars. For him, the photos capture moments of joy that feel distant when he returns home to La Carpio, a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Costa Rica’s capital.

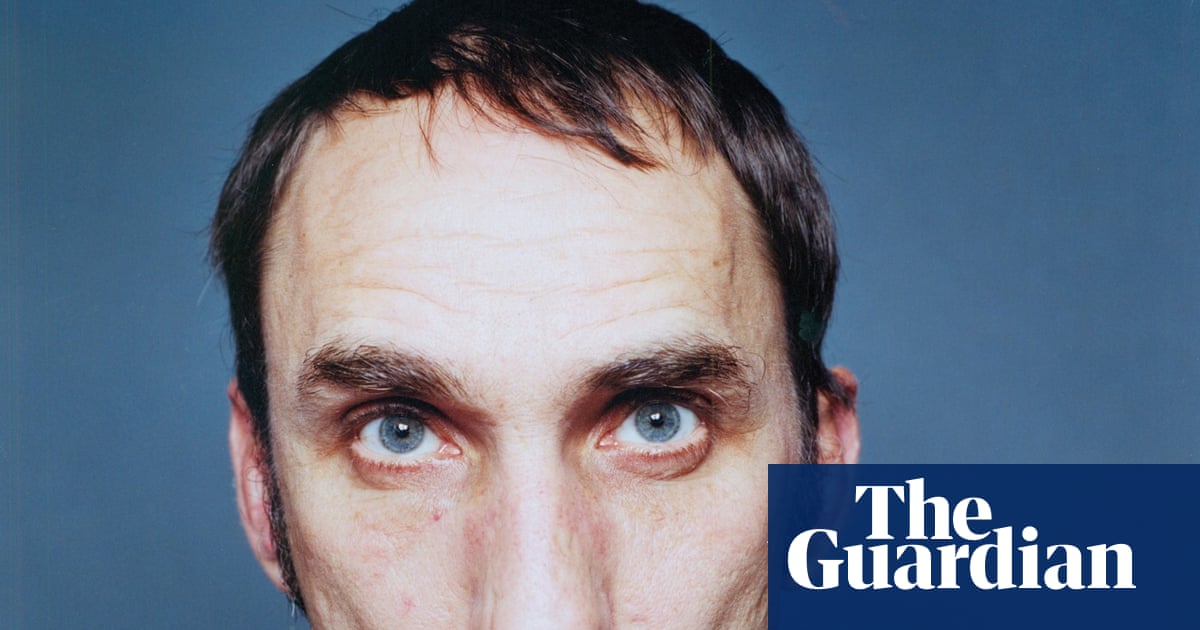

Delgado migrated with his family from Nicaragua to Costa Rica when he was 10, as his parents sought greater stability. When he started a family of his own, his greatest hope was to give his children the security he had lacked. But now, that hope is often interrupted by the threat of extreme weather events.

His community in La Carpio, most of whom have Nicaraguan roots, live squeezed between the unstable banks of the Río Torres and a steep hillside. Each time it rains, they face a double risk: the river swelling on one side and potential landslides on the other. Despite official reports deeming the area uninhabitable, government action has stalled.

At about 4am on 10 October, Delgado woke to the sound of rushing water behind his house. It was not the first time, but the heavy rains and winds knocked out the steel panelling on the side of his home. The weather grew so bad that he and his neighbours were told to evacuate temporarily.

The storm severely damaged several homes, and Delgado started leading a community effort to relocate vulnerable families to safer ground. He shared photos and videos on his Facebook page, which he renamed Río Torres La Carpio, and joined conversations on other people’s posts to raise awareness about his situation and that of his neighbours.

“I want to go to a better place,” says a video in one of his posts.

Delgado is trying to raise funds to buy land outside La Carpio, where families can build safer homes and find a path towards a better future. His cause has gained the support of Gail Nystrom, founder and director of the Costa Rican Humanitarian Foundation, an organisation that has led work in La Carpio for more than two decades. The pair plan to raise money to buy land in the neighbouring province of Alajuela, where affordable and sustainable shipping-container homes would be built.

The relocation is slated to begin with 10 families, including Delgado’s and Patricia Meléndez Narváez’s, whose home was destroyed in the 10 October storm.

Narváez, a single mother of six sheltering at her sister’s house in another part of La Carpio, was among the first to express interest in the relocation project. As a low-income Nicaraguan, she spends much of her earnings on bus fares to San José. She sells fruit, but her family faces food insecurity. Her eldest child, born in Costa Rica and now in high school, has started working to earn money.

“The most important thing is a stable life for myself and my kids,” Narváez says, adding that her children grow nervous whenever it rains. “If we could build a new house somewhere away from the river it would bring us the space we need, but also the stability.”

As the climate crisis has intensified, hurricanes have hit Costa Rica hard, including Otto in 2016, Nate in 2017 and Eta and Iota in 2020, which brought flooding and landslides causing damage worth hundreds of millions of dollars and displacing thousands. After Otto, 5,500 people were evacuated.

In November 2024, floods displaced more than 800 people as rivers overflowed. Water scarcity affects 42% of the population, as drought damages agriculture, reduces water resources and increases migration from the most affected areas.

The 10 October storm last year prompted immediate support from emergency responders and the Costa Rican Red Cross, as well as a risk assessment carried out by the National Commission for Risk Prevention and Emergency Care.

The assessment, published at the end of October, confirms what many living in La Carpio have known for years – the homes on this stretch of land are highly vulnerable due to overcrowding, the steep slope and the risk of landslides. It lists several recommendations, ultimately stating that the area should be deemed uninhabitable and that families should be relocated with governmental support.

Yet since the report’s release, Delgado says he has not heard from any governing body about the potential for supported relocation.

This assessment is only the latest warning. Reports dating back to 2007 have highlighted the dangers faced by La Carpio residents, but little progress has been made in providing lasting solutions.

Advocates such as Vanessa Vaglio, a Costa Rican who works on cleanup efforts for the river, say the responsibility for relocating these families lies with the municipal government. “The conditions they are living in are inhumane,” she says. “While independent organisations have stepped up to help, the municipality of San José has not done enough to address the problem.”

Nystrom says Delgado’s initiative can help to forge a path forward, even without government action. Situations such as Narváez’s, she says, underscore how families already living on the margins suffer the most when extreme weather events happen.

“Where these people are living is not healthy,” Nystrom says. “It’s uneven ground and there’s always a risk of a home washing away. If we can get them to safer, more stable ground, even just a few families at a time, it will make a difference.”

In Delgado’s fight for a better life, every step taken is progress. As this rainy season concludes, he and his family cling to the hope that by the start of the next, their situation will be different – safer and more stable.

“I left Nicaragua looking for a better life, and I know there is still a lot to do,” Delgado says. “It’s a long road, but we have to take it step by step.”

4 weeks ago

29

4 weeks ago

29