On a heat-dazed afternoon in Culiacán, the capital of Mexico’s Sinaloa state, a tannoy by the cathedral was droning through an advert for the judicial elections on loop when a plume of smoke appeared in the sky. A flicker of agitation ran through the plaza.

After months of cartel conflict, Sinaloa is on edge. Yet on 1 June, it and the rest of Mexico will start to elect every judge in the country, from local magistrates to supreme court justices, by popular vote.

It is a world-first democratic experiment, but one that has prompted warnings of low turnout, a political power grab and infiltration by organised crime.

The reform is the most radical move made by the governing Morena party and its allies since they won a congressional supermajority last year allowing them to change the constitution at will.

Few disagree that Mexico’s judicial system needs change. Justice is inaccessible to many, corruption is commonplace and impunity is rampant.

Morena claims its reform will address these issues by making the judiciary more responsive to popular opinion.

But critics say it will bulldoze the separation of powers, and that by throwing the doors open to less qualified candidates whose campaigns may be backed by opaque interests – including organised crime groups – it could aggravate the very problems it seeks to solve.

Delia Quiroa, a well-known advocate for Mexico’s disappeared, is no fan of the reform. But she admits it has given her a chance to become a federal judge she would not otherwise have had.

It is just the latest unexpected turn in a life that was shattered the moment her brother, Roberto, was disappeared on 10 March 2014.

Though born in Culiacán, Quiroa moved to the border state of Tamaulipas when she was a child. She had been studying to become an engineer, but as the years stretched on with no sign of her brother, she retrained as a lawyer to force the authorities into action.

Threats from criminal groups eventually displaced her family to Mexico City. Then last year they moved back to Sinaloa, which for years had been relatively calm owing to the dominance of the eponymous cartel.

“People used to say that the narcos in Sinaloa left the public out of [their fights],” Quiroa said, with a rueful smile. “Then this conflict began.”

In July 2024, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, who founded the Sinaloa cartel with Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, was detained by US authorities along with one of Guzmán’s sons after a small plane touched down in Texas.

El Mayo accused El Chapo’s son of betraying and delivering him to US authorities. Now a faction led by El Mayo’s son is waging war against another led by the two sons of El Chapo who remain free in Mexico.

As the conflict enters a ninth month, it has left well over 2,000 dead or disappeared.

And it has made the judicial elections even more complicated.

“The violence has hit the campaign,” said Quiroa. “You can’t always find people in the streets.”

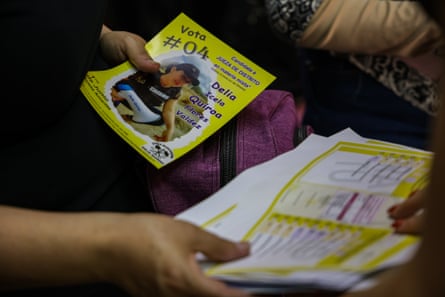

The city centre market was Quiroa’s target for the day. Friends and family came along, handing out pamphlets with her logo: a spade and a gavel crossed over the scales of justice.

“I try to explain that I have no political or economic interest in this,” said Quiroa. “That the only thing I want is a change in this country.”

But as Quiroa bounced between market stalls, people’s responses did nothing to dispel fears of an uninformed vote come 1 June.

Unlike in other elections, parties cannot support candidates, nor can candidates openly profess a partisan affiliation, even if they clearly have one.

Radio and TV spots are also banned, meaning largely unknown candidates are limited to handing out flyers and posting on social media.

Then there is the sheer number of them. Voters will be faced with at least six ballot papers, some with dozens of names on them but little else. “It looks like an exam,” sighed Quiroa.

Even an enthusiastic supporter of the reform – a butcher behind a pile of cow hooves, who celebrated the election as a chance for “the people to stop the robbery” – could not name a candidate.

Others were sceptical, if not cynical. “I’m not going to vote for candidates I don’t know,” said one shoe shiner, who was reading a dog-eared biography of 19th-century president Benito Juárez. “Just like I won’t eat a meal if I don’t know what’s in it. It’s common sense.”

According to the president of the National Electoral Institute, voter turnout is expected to be less than 20%.

Even though Morena is not allowed to back candidates, many assume it will use its unrivalled capacity to mobilise voters to help its preferred candidates – particularly for the supreme court, which has often acted as a check on Morena’s executive power, and a new disciplinary tribune, which will keep judges in line.

“Morena wants to hoard all the power,” said the shoe shiner. “They don’t want to leave a crumb for anyone else.”

But other interests, including organised crime, may also seize the opportunity.

Defensorxs, a civil society organisation, has identified various “highly risky” candidates, including a lawyer who was counsel to El Chapo and a former state prosecutor in Michoacán accused of alleged involvement in the murder of two journalists.

“I don’t think people have managed to find out who the candidates are and what each kind of position actually does,” said Marlene León Fontes, from Iniciativa Sinaloa, a civil society organisation. “People will vote on the basis of personal connections or political parties

“It’s a blind date with democracy,” she said.

If Quiroa emerges a judge, she says she will be an “iron fist” against corrupt and negligent authorities – not least when it comes to searching for the more than 120,000 people registered as disappeared, and identifying the 72,000 bodies in Mexico’s morgues.

“It was the feeling of being tortured by the authorities who should be protecting me that made me put myself forward as a candidate,” said Quiroa.

Yet as far as Quiroa knows, she is the only candidate to have emerged from the many thousands searching for their relatives.

“I’d have liked there to be more – and more victims of all kinds who are lawyers and human rights defenders,” said Quiroa. “But many people said they didn’t want to be part of the destruction of the judicial system.”

Quiroa shares their anxiety.

“This is an experiment,” she said. “And we don’t know how it’s going to go.”

3 months ago

95

3 months ago

95