It is sunrise on mount Muhabura, an inactive volcano on the Ugandan-Rwandan border, and Dr Benard Ssebide is in a rush to find a family of mountain gorillas before the tourists arrive. A mass of ferns, vines and thistles encroaches on the path, and the guides hack through brambles with machetes. Above, the forest whistles in the wind, glowing in the morning light.

“The higher you go, the more the mountain pushes back,” Ssebide says, pausing for breath.

After nearly 45 minutes, a ranger spots patches of flattened grass and large piles of fresh, dark green dung. We are close.

Then the forest suddenly opens up to nine mountain gorillas – the Nyakagezi family – having their breakfast in a clearing. The enormous silverback munches his way through a thistle, throwing his visitors an indifferent glance.

Nearby, a three-year-old juvenile swings on a vine watched by its mother. An adolescent male tugs at a wild blackberry, carefully picking off leaves to eat and grunting with satisfaction.

The Virunga mountains, which range over the border region of Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), is one of two remaining homes for this endangered gorilla subspecies, identifiable by their thick fur and stocky frames that help them withstand the harsh conditions.

In the 1970s and 80s, barely 250 mountain gorillas were left and naturalists feared extinction was close, as expanding agricultural frontiers and logging devoured their habitat.

But decades of intense conservation efforts – through war and the 1994 Rwandan genocide – have worked. Population numbers reached more than 1,000 in 2018 and mountain gorillas were downgraded from critically endangered to endangered by conservation authorities. Next year, an updated count is expected to show another increase. But it has come at an enormous cost in money and human life, and nobody who works with the animals is certain of their future.

In the past two decades, more than 220 rangers have been killed in the DRC side of Virunga national park where M23 and other militias and bandits operate with impunity. Thousands of people have been displaced and killed. Even in the safe regions of the apes’ range, the threat from human diseases is growing.

As gorilla numbers continue to increase in their last remaining islands of habitat, there is a new concern: what happens if they run out of room?

In the dense jungle of Muhabura, Ssebide, from the conservation organisation Gorilla Doctors, and his colleagues Dr Nelson and Dr Fred get to work. From a distance, they check the health of each animal, paying close attention to any signs of sickness or injury.

“They are all feeding well,” he whispers.

Gorilla Doctor vets, who work across all three countries, are key to the turnaround in mountain gorilla numbers, one of the greatest conservation success stories of the past century.

One study attributes half of the increase to the vets and their preventions of dozens of deaths, enabling the population to slowly grow.

“We have relationships with so many gorillas. Mark [this family’s dominant male] is just one. There are others. There is another born at Christmas in 2000; I saw him as a baby – now he is a silverback leading his own group,” Ssebide says.

When the Gorilla Doctors first started, much of their time was dedicated to dealing with injuries from the primates becoming caught in or lacerated by traps meant for buffalo and antelope in the forest.

Now respiratory diseases passed from humans have become a bigger problem. Anyone observing the animals now must wear a mask, disinfect their hands and keep their distance.

The threat from human colds and flu reflects one of the contradictions at the heart of conservation: humans remain the biggest ongoing threat to gorillas while also being the source of their salvation.

‘Life here has improved’

In his immaculate khakis, Chemonges Amusa is not a man to be messed with. Stretching his arms around his fellow rangers outside their headquarters, he laughs: “I am the silverback here. These are my blackbacks. Any challenge, big problem.”

Amusa is the senior warden in charge of the southern section of Bwindi Impenetrable national park in Uganda, the other stronghold of mountain gorillas, and oversees a lucrative chunk of the gorilla business for the Uganda Wildlife Authority.

Earlier that morning, two groups of foreign tourists – each paying $800 (£585) for one hour with the gorillas – had received their safety briefing.

They will see “habituated” mountain gorillas: primate families adapted to being around humans. They are not tame, but have undergone a multi-year process to allow tourist groups to stand metres away as they feed and socialise. Without training, the gorillas would flee from, or attack, people who get too near to them.

More than half of the family groups in Bwindi, home to about 460 mountain gorillas, are habituated and regularly visited. Local communities receive a 20% share of the revenue from tourism, and want more gorilla families to undergo the process.

As the visitors arrive just after sunrise, 30 women sing and dance to welcome them. A dozen porters wait nearby, hoping to carry bags. Those who struggle with the hike can pay local people $300 to carry them up and down steep hills.

Habituation – and the economy that has sprung up around it – has been another pillar of conservation success. The money from the more than 40,000 tourists who visited Bwindi in 2024 raised enough to fund the entirety of Uganda’s national park system for a year, says Amusa.

Just as in Virunga, the Bwindi gorillas are hemmed in by subsistence agriculture, a dividing line between apes and humans. But the money from ecotourism has helped to fund buffer zones, made by planting tea – which gorillas will not eat – around the forest, discouraging them from feeding on crops.

“We have to habituate for two reasons. One is for tourists, who cannot visit the gorillas if they are very wild – it would be dangerous. The other is so we can monitor them,” says Amusa. “We are very proud of our work. I am happy to see them alive and increasing in numbers,” he says.

There is enthusiasm for the gorilla conservation among the villagers, even though it has been a fraught process. In 1991, hundreds of people were moved from their homes when national park boundaries were formalised and the land protected. In some forest areas, Indigenous Batwa hunter-gatherers (formerly known as Pygmies) were forced out. But there have been major efforts to find a balance and funnel benefits back to communities.

Buhutu Steven, a 44-year-old tea farmer, tends to acres of plants. His land borders a Batwa forest reserve.

“I feel I contribute to the gorillas’ protection. When I got engaged in planting the tea, it was one way of looking after them. Before, the gorillas were at risk,” he says. “When they habituated gorillas, life here improved. Guests come and they leave something behind.”

More room

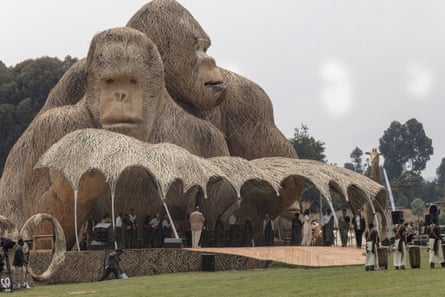

The gorillas have become a booming industry across the border in Rwanda, too. Were it not for an enormous bamboo stage constructed in the shape of two gorillas, you could be forgiven for confusing Kwita Izina – Rwanda’s annual naming ceremony for baby gorillas – with a music festival.

From early in the morning, a DJ blasts music in the shadow of the Volcanoes national park’s mountains, on the Rwandan side of the Virunga massif. Celebrities, conservationists, artists and businesspeople gather alongside park rangers and guides, with high-profile guests invited to name a baby. This year is a bumper ceremony: 40 babies need a name.

“This puts the Super Bowl half-time show to shame,” says the film director Michael Bay before introducing his baby gorilla, Umurage, which means “heritage”, to the crowd. He promises to make the “good-looking” infant a movie star.

The ceremony, marking its 20th anniversary, is a stark contrast to how things used to be. Near here, the primatologist Dian Fossey was murdered in 1985 during her campaign against poachers. Today, the Rwandan government is increasing the park size by nearly a quarter to provide the gorillas with more habitat. The country has also embraced a high-end ecotourism model. Each visitor pays $1,500 to visit the animals, and some hotels charge more than $20,000 a night.

As gorilla numbers creep up, the success of the model is obliging conservationists to consider what may happen if more mountain gorilla habitat is needed in their last two remaining strongholds.

“Right now, the park is still big enough for the gorillas. We need to work out the carrying capacity. But in the future, if the numbers overwhelm us, the government will ask the community to create more land for them, both for their habitat and the buffer zone,” says Amusa in Uganda.

Researchers will watch for signs of fighting between gorilla families, an indicator that numbers are putting strain on the available habitat. But for now, most are satisfied that predictions of mountain gorillas’ annihilation have been proved so wrong.

“The records indicate there were many more gorillas here before. I think these areas could take three times as many,” says Ssebide. “But ultimately, you will never know what will happen as the population grows.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage

3 months ago

52

3 months ago

52