I am an eight-year-old girl, standing near-naked in a room full of strangers.

As the room spins and zooms upon me and people glide around me, I clock my features.

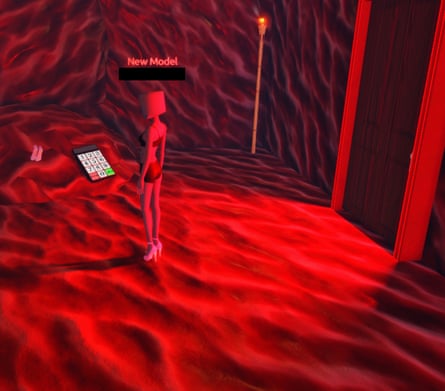

I don’t look eight. I look like a grey Barbie doll, complete with cleavage and bare feet locked uncomfortably in the high-heel position. I have a large block head that resembles a grey marshmallow.

I’m in the world of Roblox, where block-like avatars transform themselves to explore a universe comprising millions of user-generated games. The platform boasts more than 100 million active daily users. Almost half are children under 13 and, in Australia, a 2024 study found that kids who used the site play for an average of 137 minutes a day.

On Wednesday, the eSafety commissioner Julie Inman Grant said that Roblox would not be captured by Australia’s new social media ban, but warned it remained “on the line” as the ban was continually assessed.

“We’re using other tools in our arsenal to keep these other platforms safer… just because a platform is exempted through the legislative rules doesn’t mean it’s safe.”

Over the course of a week I log on to the platform as a child to experience first-hand the gaming app of choice for Australian children. In my short time there my avatar is cyberbullied, aggressively killed, sexually assaulted and shat on – all with parental control settings in place.

My skinny grey self starts by visiting one of the most popular “experiences” for young girls, a game called Dress to Impress which has had more than 6bn visits since its November 2023 launch. At its peak, the game had more than a million concurrent users. Vogue has reported that adult fashion junkies have joined the game’s devoted child fanbase, while the game has been promoted as a “household brand in fashion and gaming”.

Clumsily, while soundtracked by a smooth synth jazz track, I begin to explore. The gap between my thighs is almost as wide as my waist is narrow.

OK. I’m starting to get it. I have to choose an outfit according to a theme as a clock counts down. Some areas – including the VIP Lounge – are off limits unless I spend real cash, known across Roblox as “Robux”, but otherwise I have a small department store of clothes and accessories to choose from.

I hustle to assemble a “sci-fi” outfit, scrambling to find clothes and work out how to put them on.

I spot a scanty two-piece number but am yet to find a face.

Oh, a knife! Yes. I might need that.

Cat ears? Why not.

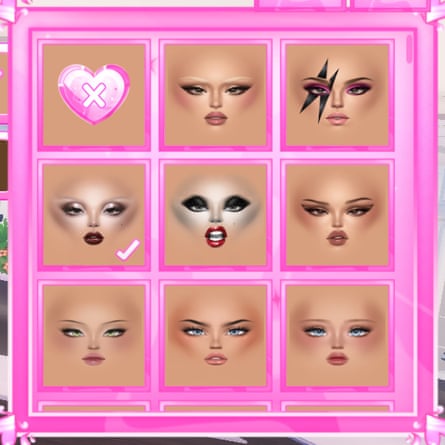

Still hunting for a face, I try the makeup room. Here a dozen or so heavily made-up faces are on offer, with looks ranging from RuPaul to Ziggy Stardust.

I end up with a Bratz doll-like head on some kind of stripper Barbie body.

Getting here was easy. On sign-up Roblox asked for a username (specifying it should not be my real name) and a date of birth. It asked me to tick a box confirming that “your parent/guardian permits you to create this account and agrees to our Terms of Use”. Sure.

The point of the game I’m now in – known as DTI to its fans – is to dress and be judged by my fellow players.

Once the five-minute countdown finishes, players strut the catwalk and are rated on a scale of one to five stars, with rivals able to chat or post commentary in the open chat box. Players can strike a variety of poses – some are free, while other “pose packs” cost Robux.

I give everyone five stars, hoping to boost any flailing confidence among other users.

Players discuss the appearance of others in the chat box that seems as often disparaging as it is encouraging. The game’s latest update lets them throw tomatoes at other contestants or surround them with a virtual pile of shit.

While promoted as a kids’ game and an outlet for creative fashionistas, a dive into the world of DTI reveals the game’s darker side.

I discover a basement “meat room” – which looks as though you’ve walked into someone’s uterus – hiding a pair of stilettos and a locked door. Other secret rooms are part of the game’s “lore”, offering creepy suggestions that a woman has gone missing. A previous update included a dungeon with a woman locked in a cage.

‘Pay to troll’ features

DTI’s devoted fanbase is getting restless.

Users are complaining of updates that force them to spend more Robux to remain competitive. The increasing monetisation of children’s games is a widespread criticism of the platform.

Marcus Carter, a professor in human-computer interaction at the University of Sydney, likens the site’s in-game spending promotions to “child gambling”, pointing to countless casino games and “loot boxes” within games that are readily available to children.

He spent a fruitless three weeks trying to get a refund for a lootbox bought as a 12-year-old on the grounds that they are illegal to sell to children in Australia.

He has also tracked the rising phenomenon of “pay to troll” features – such as the shit-throwing on DTI – which incentivise bullying and prompt players to pay real money to do so.

“Roblox games are actually monetising that kind of desire to troll and mess with and negatively impact other players,” he says.

Roblox is big business. It is a US$92bn listed company in the US, owned predominantly by institutional investors. The chief executive, David Baszucki, owns about 10% of the company’s stock.

Successful game creators – many of them children – can make money. In 2024-25 the company’s developer exchange program paid out more than $1bn through a convoluted payment plan under which the company keeps at least 30% of transactions made on the site.

Developers earn Robux and can cash out US dollars once they make a certain amount. Last year’s median payout figure was US$1,400.

Carter says while the platform does allow children to learn how to code their dream game, Roblox is essentially exploiting child labour through play – termed “playbour”.

“Roblox really celebrates these instances of teenagers becoming millionaires because their games blow up on Roblox but this is all child labour,” he says. “All of its income comes from the games that its users are making.”

Roblox has rejected suggestions it relies on child labour, saying most of its developers are over the age of 18.

Carter says venture capital-backed firms are buying popular games, with teams of developers and data analysts working out how best to extract more money out of their child player base.

This year a leading Roblox role-playing game, Brookhaven, was bought by the game developer Voldex with the backing of the venture capital firms Raine Partners and Shamrock Capital.

Other big businesses are moving in. This month the toy brand Mattel announced it would be expanding its gaming business in collaboration with Roblox and Fortnite, launching a Monster High game with other of its brands, including Barbie and Hot Wheels, to follow. Last week the AFL also announced it was launching an official Roblox game to connect with gen Z and gen alpha users.

DTI’s popularity has brought it high-profile collaborations with Lady Gaga and Charli xcx. It has released a line of DTI dolls and is promoting a forthcoming Wicked: For Good release to coincide with the film’s US release next month.

But as the game has become more mainstream, complaints are growing about inappropriate content for children.

Last month DTI removed a new pose called “serve it” – bending over from the hips – after a backlash. A Reddit post in response to that release was titled: “Someone needs to warn the parents.”

Then there are users who dress in “fits” that look naked, despite the presence of young children on the game. Roblox says DTI is suitable for children aged five and over.

In seeking to understand who is responsible for the game being played by millions of children worldwide, I stumble across yet another layer of complexity in the Roblox ecosystem. It’s incredibly difficult to find out who owns and operates each experience.

after newsletter promotion

The corporate entity for each game is not published anywhere. All the information in the public domain suggests that DTI is largely owned, managed and moderated by teenagers.

Information released by Roblox shows DTI was developed by a user known only as “Gigi”. Gigi, whose gender and nationality are not provided, claims to have been 16 when the game was released and started developing it at 14.

Last year, responding to allegations of inappropriate interactions aired on social media, Gigi admitted to making “a vile and disgusting” joke about rape and to making fatphobic jokes. They also admitted to hosting a NSFW (not safe for work, meaning “adult content”) server on the Discord messaging and social media platform while underage.

“I want to be clear, no pictures of minors were ever shared,” Gigi says. “Yes, it was a NSFW server, which in hindsight is really gross and inappropriate, but at the time I was literally just a bored kid.”

The immaturity of the game’s management team was evident this year when serious allegations were raised against one of DTI’s most senior employees.

A 20-year-old administrator was accused of grooming a 16-year-old. This had happened outside the game on an unrelated server.

In response to the allegations, the staff member released a statement saying they had become friends with someone who “while not legally under the age of consent, was still too young for me to have become friends with at the time”.

“I made very inappropriate jokes and said very inappropriate things,” the administrator said, revealing that they had been experiencing depression, anxiety and severe body image dysmorphia at the time.

The imbroglio prompted the game’s manager – an 18-year-old known as Umoyae Free Spirit – to announce that the employee had been dismissed.

She said the game was “considering making the moderation team 18+”.

While Roblox claims responsibility for managing its “community standards” on the site, including cases of abuse, the company has sought to exempt itself from laws relating to social media by arguing it is merely a platform hosting other people’s games.

A Roblox spokesman said the platform was “committed to leading in safety through rigorous policies that go above and beyond what other platforms do”.

“We use AI to check for violative content before a game is published, we do not allow users to share images or videos in chat, and we use advanced text filters designed to stop kids from sharing personal information,” he said.

Guardian Australia contacted the manager of Dress to Impress for comment, but did not receive a response.

‘Perfect place for pedophiles’

Roblox has long faced accusations of being an unsafe platform for children and being frequented by paedophiles. In late 2024 the investment investigator Hindenburg Research called it “an X-rated paedophile hellscape”.

Since then, the company has been hit with multiple lawsuits in the US, outlining tragic circumstances in which minors were groomed online and abused.

In August the attorney general of Louisiana alleged that Roblox’s safety failings had created “the perfect place for pedophiles”.

A lawsuit filed in California in July is seeking damages for an 11-year-old who was violently raped after she was groomed on the platform by a now-convicted paedophile. The case accuses Roblox and Discord of “systemic failures to protect society’s most vulnerable from unthinkable harm in pursuit of financial gain over child safety”.

In another lawsuit, a mother of a 15-year-old who took his own life accused Roblox of “recklessly and deceptively operating their business in a way that led to the sexual exploitation and suicide” of her son.

Roblox does not comment on pending litigation but after the Louisiana lawsuit was launched it said: “Every day, tens of millions of people around the world use Roblox to learn STEM skills, play, and imagine and have a safe experience on our platform. Any assertion that Roblox would intentionally put our users at risk of exploitation is simply untrue.”

At the same time as the flurry of lawsuits, the platform controversially banned a user called Schlep after the Texas-based YouTuber, himself previously groomed on the site, worked with law enforcement to pose as a young gamer and out predators.

Roblox issued him with a cease-and-desist order and removed him from the platform.

In Australia the e-safety commissioner has been negotiating with the company on a range of new safety measures after raising concerns about “child grooming risks”. By the end of the year the company has committed to making accounts for under-16s private by default and introducing tools to prevent adults from contacting them without parental consent.

A number of key features will be switched off by default for children in Australia, such as direct chat and “experience chat” within games, until the player has gone through age estimation. Parents will be able to disable chat for 13- to 15-year-olds.

“While no system is ever perfect, we have made over 100 safety enhancements this year alone to help protect our users and give parents more tools to manage and monitor their child’s online experience,” the company spokesman said.

But, as I continue my experiment logged on to the platform as a child, I come across many more experiences that are clearly inappropriate.

In one game – a vibe hangout where I am logged in as a 13-year-old – it doesn’t take long for another avatar to sexually assault me. He sits on my face and repeatedly thrusts his hips while I implore him to leave me alone.

A group of male avatars later call me an “ugly bacon dirty gross girl” in reference to the bacon-like hair on my rookie default avatar.

In another popular role-playing game – Berry Avenue – someone follows me around and pretends to shit on my head and face, calling me a toilet.

Another game my eight-year-old avatar can access with all parental controls in place is called Suffer. After entering and arming myself with an axe and an ice-hockey mask I am immediately machine-gunned down.

A friend reports that her 10-year-old son is hooked on a game called Prison Pump. I’m called “fresh meat” on entry and taunted for being a weakling. I have to start pumping iron or pay for more muscle. It isn’t long before four giant “hombres” beat the life out of me.

I can access bathroom simulator games, dungeons, casinos, horror games, escape rooms and countless role-playing games where I can send and receive messages from strangers.

The number of inappropriate games I can access while logged on as a child appears endless.

It’s for this reason Carter, who is keen to emphasise the positive benefits from gaming and digital play, says he doesn’t have a good answer when parents ask him how they can know their kids are safe on Roblox.

“My son is four and I do not intend to ever let him play Roblox,” he says. “My life is about video games; I am a professor of games at the University of Sydney, I love games, my son and I are going to be playing lots of games together – but not Roblox.”

Do you know more? Contact [email protected]

2 months ago

38

2 months ago

38