In August 1978, I was born in a hospital in Stamford, Connecticut. I came out with red hair. This was proof to my mother that I was special. The fantasy of my specialness continued my entire life. I was special even though I was dyslexic. I was special even though I got kicked out of college. I was special even though I was a drug addict. I was special despite my fatness. I was special despite all the evidence to the contrary. I was special because I was a piece of her.

I read an interview with my mother in which the interviewer described me as a “stout” toddler. “Stout” means “kind of fat”. I never thought of a toddler as being able to be fat, but there it was.

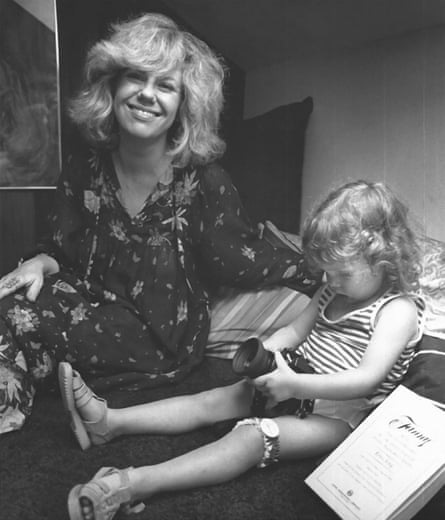

This is from that interview in the Washington Post: “Their daughter, Molly Miranda Jong-Fast, is two years old and red-headed. She was born between pages 284 and 285 of Fanny. Having the baby, Jong says, ‘transformed’ her. ‘In my 20s and early 30s I didn’t think I wanted children,’ she says. ‘But by the time I was 34 or 35, I realised that if I didn’t have a baby soon, it was going to be a matter of picking up every stray dog in Connecticut.’”

I always wondered if she would have been better off with a dog.

My mother is the writer Erica Jong. She is a novelist, essayist and poet. She has published 27 books, the most famous of which is her autobiographical novel Fear of Flying. It came out in 1973, five years before I was born, and is considered, in some corners at least, a landmark of feminist literature. Its candid depiction of women’s sexual desires was extremely shocking at the time. It has sold more than 20m copies, and John Updike compared it to The Catcher in the Rye and Portnoy’s Complaint. Fear of Flying made her very famous, for a writer. She was a guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. She was on the cover of Newsweek. Gore Vidal and Henry Miller were friends. I’m not here to brag about my mother’s friendships with dead writers. But a lot of younger people have no idea who she is.

My mother coined an expression for casual sex: the “zipless fuck”. Now think about being the offspring of the person who wrote that sentence. And pour one out for me.

I grew up with her everywhere – on television, in the crossword puzzle, in the newspaper. Mom was a kind of second-wave feminist, a white feminist, and an (highly educated, wildly affluent, Jewish and somewhat out-of-touch) everywoman. But she wasn’t an actual everywoman, of course; she was too famous for that. Too famous, and too special. She was famous for that book, then later she was famous for being famous, and then eventually she wasn’t famous any more. Because fame, like youth, is fleeting; it deserts you when you least expect it. The wheel of fortune is always spinning.

I never thought of myself as the star of my own life, or my own childhood. From a young age, I knew my mom was writing about me. I knew it because people would come up to me and ask me very personal questions, which meant that they knew things about me they couldn’t possibly know unless someone was telling them. I never knew quite what the other person knew about me. In some ways, it made me very good at talking to people; in other ways, it made me a psychopath. I never had privacy, so I never valued privacy. I just assumed everyone knew everything about me and about everyone else.

When I was a kid, my mother published a children’s picture book about me because of course she did. She told me she wrote Megan’s Book of Divorce to help me deal with her divorce from my father. It’s a crazy piece of work. A blog called Awful Library Books had some fun with it, referencing, among other transgressions, something called “the bizarre underwear scene”. In the scene in question, I (or “Megan”) am not wearing underwear. I’m kneeling before my toy box and appear to be fellating a stuffed dog (naturally, I’m looking for my missing underwear). I am given the line, “I think divorce is dumb because I never remember where I left my underpants.” The publishers liked the butt drawing so much, they also put it on the back cover.

This is not the only problem with the book. There is the reflexive racism (one of Megan’s nannies, Bessie-Lou, has “healin’ hands” and takes young Megan “to meet her pastor in Harlem. Hallelujah!”). There is the fact that Megan wants her mother to kill her stepmother. There are continuity issues, there is the ever-present Erica Jong problem of unexamined privilege, but the most obvious and tragic problem: the author of the book seems to have about as much familiarity with children as she would with extraterrestrials from Mars.

Believe it or not, my mom sold the film rights to this picture book to ABC. A pilot was shot. They changed the title to Sam because my dad threatened to sue my mom unless my name were changed. (Although my name in the book had already been changed to Megan. By that point in my life, I had learned not to ask too many questions.)

As another data point from the Megan’s Book of Divorce debacle, I would like to submit this correction from a piece about me written in the New York Times in 2022, which, for those keeping track at home, is 37 years after said sitcom. The correction was sent in by my father, who said: “An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Molly Jong-Fast’s father, Jonathan Fast, sued her mother, Erica Jong, over Ms Jong’s depiction of a fictional character based on Ms Jong-Fast and her experience with her parents’ divorce. Mr Fast’s lawyer was involved in the dispute, but he did not file a lawsuit.”

When the pilot was filmed in 1985, my mother took me out of school and moved us to LA for a month. We lived at the Beverly Hills hotel. I don’t remember much about living in LA except that it was yet another time when my mom was convinced that she had made it and wouldn’t have to worry about money any more. But the show was not picked up and we went home.

What ended my parents’ union, I never could get a straight answer about. The reason I knew Mom was a liar was because her story always changed. Sometimes it was one thing, then sometimes it was an entirely different story. This shifting reality, this strange post-truth ecosystem she inhabited, and that for a time I inhabited, too, made me completely unable to know what was real and what was a lie with her. It was a kind of gaslighting by proxy, like Munchausen syndrome, but somehow much, much stupider. I grew up with a lot of mistrust about people. I was prickly. I was hard to connect with. I didn’t trust anyone. When I got sober at 19, I learned how to be an actual person. Before that I would do all sorts of alienating things and feel surprised when people felt alienated by me.

Later my mother admitted they had an open marriage. My father, when questioned about this, said only, “Yes, she thought it was open.”

“He was just too jealous of me,” she would tell me. My father was, at the time, working towards a master’s in social work. She said that kind of thing a lot, and about a lot of people. My father often said she was impossible to live with, an experience I’ve had first-hand. Should I blame the way she became on her fame, on all the years of people telling her she’d changed their lives? Or perhaps she was always like that.

By the time I was born, Fear of Flying was already five years old. My unfamous father married a very famous woman, though they actually didn’t get married until my mom was pregnant with me because they both believed marriage was a bougie construct.

My father’s famous father, communist hero Howard Fast, hadn’t been jailed or blacklisted since the 1940s, but he was still famous – or notorious – sort of. And Grandpa ended up back on the New York Times bestseller list much later, too, in the 80s, with a bunch of pulpy historical fiction novels. So my father had the double bad luck of being married to a famous writer and being the son of a famous writer.

Even back then, I think that Mom was anxious about losing her fame. Mom clearly understood that fame was, even for most famous people, a temporary state. She was always convinced that someone might try and take her career away; the problem was, she was pretty sure it would be me.

Eventually, my dad moved out of our house. It was one of those epic divorces with teams of lawyers. And then my mom also moved out of the house! She left me in Weston with my nanny, Margaret. Mom moved to New York and did the very 70s thing of sharing an apartment with another single gal. Let’s politely call the place where they lived their bachelorette pad. I stayed in the house in Weston for a year with Margaret, and eventually we were summoned back to New York. My mom had met a guy named Cash. He was in his 20s, and handsome. I assumed he was dumb, maybe he wasn’t. He was gone by the time I was old enough to make an assessment either way.

Mom kept the place in Weston as her country house. I grew to loathe that house. Mostly it was the association of being left there alone with Margaret that year. It’s funny because when I was young my mom would tell me she was a great mom, then when I got a bit older, she would tell me that she practiced “benign neglect” – as if this parenting style was somehow by design.

One day after she had tried this line on me too many times (obviously she felt terrible about the sort of mother she was), I just snapped and said, “It was just neglect neglect. Benign makes it sound intentional. Stop saying that.” She never said it again.

I know how entitled I seem, complaining about my childhood. I mean, I never worked in a factory. I never wanted for one single material possession. Ever. Not once. I know how lucky I was, and am. I know how terrible the world is. But still. I want to tell the story not for any kind of pity, but for the hope that telling it will make me stop trying to relive it, will make my past go away. Even though I have spent my entire adulthood creating a different kind of life for myself, my head, my soul, my spirit – whatever you want to call it – is still stuck in the mire of my childhood.

Mom was always travelling. There wasn’t an invitation to a book fair or festival, interview or speaking engagement that she’d decline. And when Mom was at home in New York, she was out dancing at Nell’s club, or fighting with Elaine, the owner of Elaine’s, the famous (infamous?) restaurant on the Upper East Side.

Sometimes I’d be in bed and Mom would knock on my door, sometimes drunk and sometimes just tipsy, but always smelling of the most wonderful perfume. My bedroom was arguably the best room in the house – second floor, three huge windows, high, high ceilings. She’d peek her head in and stage-whisper, “I have New York Super Fudge Chunk!” Then she’d ask me if I wanted to go into her room and watch TV with her, on her bed.

This was the best thing ever in the whole world. Margaret gave me a crazy strict bedtime, but when Mom would ask me to watch TV with her, I would run right up the stairs to her room and watch TV and eat ice-cream until my stomach hurt. I loved those nights so much.

Mom would let me stay home from school the following day. She was a firm believer in mental health days. Margaret didn’t believe in mental health days, but my glamorous mom didn’t believe in the rules. Rules were for boring, unfamous people who balanced their cheque books. Rules were for normal people. My mother was not normal, nor did she want to be.

after newsletter promotion

Two infamous/notorious sexologists, Phyllis and Eberhard Kronhausen, eventually moved into our ground floor, after their landlord, Shirley MacLaine, kicked them out of her apartment on Central Park West. It was nice to have someone else in the house, even if they were old and creepy and weirdly thin and leathery. They took handfuls of vitamins every day. Eventually, they moved back to their farm in Costa Rica. They told me I should come visit and I never did. They left the basement filled with erotic paintings as a gift to Mom.

Most of the kids I knew growing up found the house, and our art, fascinating. My friend Ruthy couldn’t believe there was a painting of naked lesbians having sex at the top of the stairs. My other friend Juno wasn’t as shocked as Ruthy, but that was only because her parents were psychoanalysts and she had a male nanny.

Much of my feminist mother’s time was occupied by men. But maybe, come to think of it, this shouldn’t come as all that much of a surprise to readers of her fiction. After all, in Fear of Flying, she wrote, “Underneath it all, you longed to be annihilated by love, to be swept off your feet, to be filled up by a giant prick spouting sperm, soapsuds, silks and satins, and of course, money.” And of course, money.

She was always in love with someone. More often than not, it was a problematic man, a “no-account” count, a married writer who lived in Brooklyn, or a drug-addicted B-list actor. Between her divorce from my father (husband No 3) and her marriage to my stepfather (husband No 4), there were numerous fiances. I couldn’t help but envision each one as a possible father. It would take me years to understand that the worst thing you could do to a kid was introduce her to possible stepfathers on a daily basis. But my feminist mother was always looking for someone to save her, someone to get her out of her own head.

Where did those potential dads go? Did they end up finding other lives? Did they end up having other stepdaughters? Did they ever think about us? Even at the time I knew it was extremely strange to have all these adult men wander in and out of my life like actors auditioning for the part of playing the man who would eventually marry my mom.

Did I mention those men ended up in the books? Because they did. Everyone ended up in her novels. Anyone who knew her knew that everything that happened went right into the books. Names were changed to make everything a little more pretentious, but some things were almost reported verbatim, and sometimes they were combined with weird hodgepodges of fantasies she had about other people. But the one thing that always happened was that she was the hero, always and for ever.

I was 11 when Mom decided to marry Ken. They’d been going out for exactly 90 days. It was not my mother’s first engagement that year. But for whatever reason they decided to get married. The ceremony took place in the parking lot behind the humble ski condo Ken bought when he was living with the girlfriend who preceded Mom.

Ken loved Mom. The rest of the world barely existed, mostly their reality was just their love for each other. I could tell I wasn’t really going to be a part of this new life. (Do I sound bitter?) I could sense that Ken wasn’t going to be much of a father to me. I recognised in him a kindred spirit, though not in a good way. He was loud. He was blustery. He was used to getting his own way. He thought he was always right. He ate Steak-umms for breakfast in his bathrobe.

All these years later, I thank God for Ken. Had he not come along, I would have never survived my childhood, I would have been eclipsed by my mother’s need for me.

Mom and Ken bought an apartment and right after we moved in, they fired Margaret. I was bereft. I wept. I had lost my best, and only, friend. I know how fucked up that is.

Fast-forward to almost-present day. I spend my days feeling like a little girl wearing her mother’s enormous high heels through meetings with accountants and lawyers and doctors. I am talking to the movers and special fancy nursing home people who will charge lots of money for who knows what. Every day I visit Mom and Ken in the apartment I grew up in. They’re not children, not exactly, but they’re not adults any more either. They are like people, they look like people, but they aren’t making the kind of decisions that high- or even average-functioning people make. I will soon have to sell the apartment, at the bottom of the New York City real estate market. I have to manage things. I have finally made the decision to put my mother and stepfather in the World’s Most Expensive Nursing Home.

I came to Mom and Ken’s apartment every day with a book about the nursing home, a luxe hardcover coffee-table book with beautiful pictures of the home’s five restaurants, its gym, its spa, its espresso lounge, its yoga studio, its saltwater pool. “You like to swim, right, Mom?” I’d ask. Every day, I’d sit in their dog pee-smelling apartment and show them the pages of the book. Mom was impressed by the restaurants. Sometimes they seemed open to the idea of moving, and sometimes not. And, just like Brigadoon, the thought would vanish and every night they’d forget the conversation. So every morning I’d have to remind them.

I’d say happy, positive things like, “It’s a hotel!” and, “It’s like it’s the Four Seasons!” And it truly is like the Four Seasons. And probably even more expensive. It is beautifully designed – airy and light. I said things to make myself feel better, but it wasn’t clear that they knew what anything I was saying meant, and the reality of what I was doing did not change. I was putting them in a home. I was doing it because they both have dementia. I was doing it because I am a bad daughter who won’t devote her life to taking care of them, the way my sister-in-law did for my in-laws. I am a bad daughter. But, then again, they were terrible parents, so perhaps we’re tied.

In my dark moments, I’m honest with myself. I know what I’m doing is wrong. I know they don’t want to go there. They are special. They have always thought of themselves as just a little too special to do the stuff normal people do. They have always considered themselves to be just a little too good for normal life.

Today was move-in day. “We gave you power of attorney, and you put us in a home,” Mom said, as we arrived at the World’s Most Expensive Nursing Home. This was, on the face of it, true. Basically, the whole thing was reverse summer-camp drop-off. You lied to your parents just like you lied to your kids. But with the kids, you knew that they were going for a short period of time. With the parents, they were going for ever. With the kids, you knew you were doing something for their own good; with the parents, you were not so sure. Also, with the kids, you were pretty confident that they weren’t going to die there. With your parents, you knew they were.

A couple of days later, I called my dad, my one remaining parent. I was in a taxi heading to CNN, to do a late-night panel. I told him Mom wasn’t dead yet but she wasn’t exactly there any more. I told him all she did was sleep and drink. I told him how guilty I felt. I said that I shouldn’t be at the CNN studios. Wherever I was, I felt I should have been somewhere else. I should have been spending more time with my kids, with my parents, with my dogs, with my husband who was very ill.

My dad tried to reassure me in his own peculiar, fucked-up way. “You know,” he said, “when you were a little girl, the nanny and I used to try and get your mom to spend time with you. We tried to get her to spend just an hour a day with you.”

This admission made me feel so great.

“And she couldn’t do it,” my dad said. “She couldn’t even spend one hour with you. The most she could do was half an hour.”

Now, maybe my father was trying to use this knowledge as a way to make me feel less guilty about putting her in a home. Because when I go to visit her, she is always crying. She wasn’t a crier when I was a child, but she cries a lot now. Everyone who works there is worried about Mom. They are worried about the crying, but they are really, really worried about the drinking. And the more she drinks, the more she cries. (And the more she cries, the more she drinks.)

I am the only bit of Erica Jong in the universe except for her, but she sits in a nursing home reading and rereading the newspaper.

I had spent my entire life trying to get away from the loneliness of being abandoned by my parents. I assumed this would somehow preclude me from mourning their deaths. Like with almost everything in my life, I was deeply wrong. You can’t pre-grieve your parents, much as you might want to, or need to. As an addict, I was always looking for a quick fix, a way to skip the hard work. I was the second or third generation in the family to love diet pills. I would take them instead of eating. You can cheat your weight, but you can’t cheat grief. Even if your parents never loved you, or you never loved them, or some weird combination of the two, grief still comes for all of us.

3 months ago

60

3 months ago

60