As a Cambodian living in Thailand, 31-year-old Da, has kept her children home from school this week in fear they might face abuse.

“One of my friends went to the market yesterday to buy durian and the seller told her that she hated Cambodians,” she says, of rising tensions between the neighbouring countries.

Days after Thailand and Cambodia announced a ceasefire after a deadly five-day conflict, relations remain dangerously frayed, and peace tenuous. Since the truce both sides have accused each other of violating it, while online, public distrust is being fuelled by a bitter confluence of disinformation, threats and nationalism.

Dowsawan Vanthong, 50, who is volunteering at a temple in Surin, northeastern Thailand, that is hosting evacuated people, worries that even if calm prevails and the disputed border eventually reopens, relations won’t be the same.

“For me, I can make a distinction and separate normal Cambodians [from the government or military]… But I’m not sure if everyone could do this, especially people in the areas that were most affected,” she says.

At least 43 people were killed on either side of the border in the clashes, the worst to grip the two nations in more than a decade.

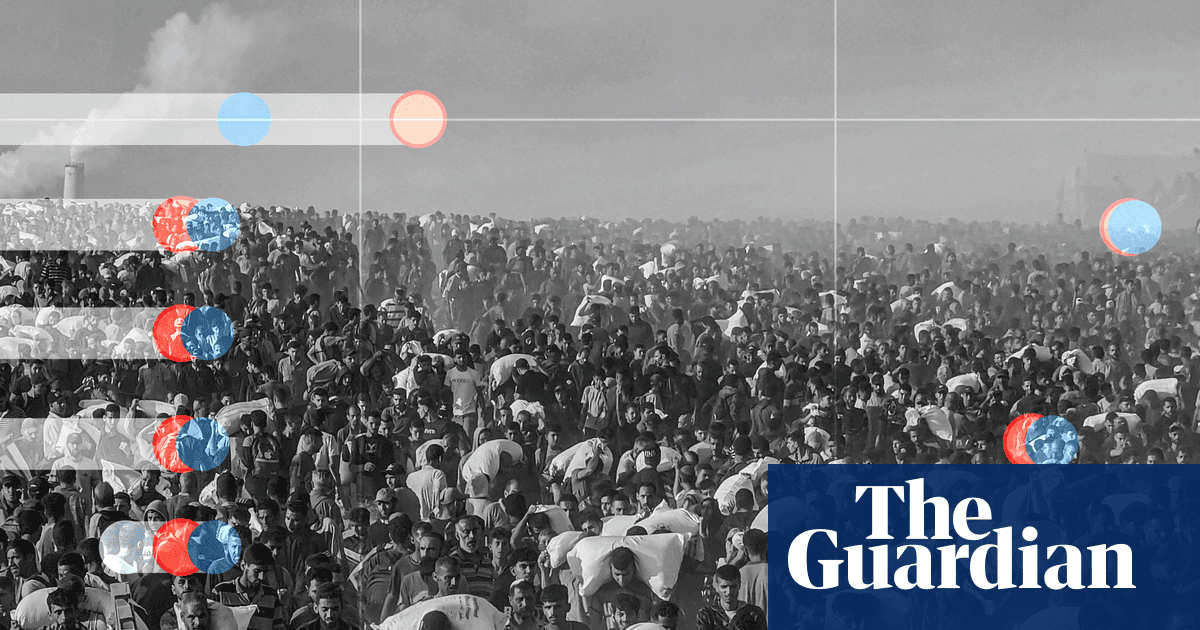

In normal times, residents would regularly cross the 800km border that separates the two countries, going back and forth for trade and work, school or healthcare. Before the conflict started, more than 520,000 Cambodians worked across Thailand, often in low-paid jobs in agriculture, construction, fishing and manufacturing.

But the border is now almost entirely shut, though Cambodians living in Thailand can return home. Thousands have queued up to do so, worried about rising vitriol in Thailand.

Da, who works as a cleaner and asked for her real name not to be published due to the tensions, says she has to stay in Thailand for economic reasons and to pay off debts, but she feels still feels uneasy about the decision. “The kids saw on social media that a lot of Cambodians are going back home, so they wanted to as well,” she says.

Social media commentaries have become increasingly incendiary and, at times, violent. In a viral TikTok clip, a Thai man appears to instruct young Cambodians to tell Hun Sen - the former Cambodian leader who remains extremely powerful – not to attack Thai people. When one of the group smiles, the man slaps him on camera. Hun Sen later shared the video on his Facebook page, warning Cambodians in Thailand to stay safe.

Another video, shared widely online, apparently shows a group of Thai people beating up a man who is reportedly a Cambodian national.

When two Cambodian women posted videos stamping on the Thai flag, part of a new social media trend, people demanded their deportation.

Thai authorities have urged young people and social media influencers against inciting violence, but the bitterness has continued to be shared online.

The South-east Asian neighbours have a long history of rivalry, especially arguments over the roots of their shared heritage. In 2003, when false rumours that a Thai soap opera actor had suggested Angkor Wat, a Unesco world heritage site, belonged to Thailand, riots erupted in Phnom Penh, and the Thai embassy set on fire.

Diplomatic rows and social media storms have broken out periodically since. Two years ago, Thailand boycotted a kickboxing event at the South-East Asian Games in Cambodia after the discipline was called Kun Khmer rather than Thailand’s name for the sport, Muay Thai. Even well-meaning posts can spiral into online wars. The UK ambassador to Cambodia Dominic Williams inadvertently created a social media furore in 2023 when he posted a picture of some sweet treats on social media, captioned “Khmer dessert”. Thai people responded with a flood of angry comments claiming the snacks were in fact Thai.

Social media, far more prevalent than the last time the border dispute erupted in 2008 and 2011, has inflamed tensions.

Some have pushed back. A major hospital in Ubon Ratchathani province was forced to backtrack after it suspended services for new Cambodian patients and announced it would be strictly “zoning” existing Cambodian patients due to the recent fighting. Critics pointed out the policy was discriminatory. But online others supported the hospital. “Shall we help them get better so they can shoot at us again?” wrote one commentator.

The public mood in Thailand – and pressure for Thai authorities to seek responsibility for Cambodian attacks on Thai civilians – could threaten the fragile ceasefire.

Ken Lohatepanont, a political analyst in Thailand, says the ceasefire will probably hold for now, but the prospects in the medium and long term are less clear. “Thailand and Cambodia are still going to have a lot of border issues to resolve, because none of the core points of contention have actually been discussed so far,” he said.

Both Thailand and Cambodia still insist on usingdifferent maps to demarcate the border.

Da, who lives far from the border, in Rayong province, is mostly staying at home, going out only to buy food and work. “In my opinion, both sides have done things wrong – they need to find a way to speak peacefully,” she says. “I want the situation to go back to normal, to open the border gates so that Thai and Cambodian people can come together again.”

3 months ago

44

3 months ago

44