When the Derzhprom building erupted on to the Kharkiv skyline in the 1920s, it must have seemed like an impossibly futuristic vision. Standing like a gleaming white concrete castle, it curves around the circular plaza of Freedom Square in the city’s centre.

Built as the state industry headquarters of what was then the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, it looks like a three-dimensional game of Tetris, a mighty nest of chunky oblong forms stacked, rotated and interlocked to form a colossal administrative pile. Striding across three city blocks, and towering almost 60m high, it was the tallest office building in Europe for several years, its humungous floor plates connected high up in the air by thrilling sci-fi skybridges. It was far ahead of its time, prefiguring the brawny brutalist complexes that emerged in western Europe and the US half a century later.

“Derzhprom was conceived as the crown of the city,” says Ievgeniia Gubkina, author of a new architectural guidebook to Kharkiv. “It was the symbol of the capital as a concrete fortress. And now, during the war, it has become the main symbol of our strength and resistance. That concrete will never fall apart – and we Kharkivites are strong as concrete.”

Gubkina, who grew up in Kharkiv, had completed the text for her book just two months before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Trained as an architect and urban planner, she had been leading tours of her home city for 15 years, and imagined the book as a love letter to the place – a love letter that suddenly became a farewell letter, when she relocated to London with her teenage daughter in July that year.

The resulting publication is, she says, something of an “anti-guidebook”, given that the UK Foreign Office advice now warns against all travel to the region. Seeing Kharkiv through Gubkina’s eyes, in text that combines poignant personal reflection with the analytic rigour of an academic, might be the only way you will get to experience the city for some time. The entries about each building remain unchanged, save for the addition of a few details about how the structures have since been mutilated – the drily written notes only emphasising the stark brutality of Russia’s invasion. Located just 18 miles from the Russian border, Kharkiv has seen more than 8,000 of its buildings damaged or destroyed in the last three years, including homes, schools, hospitals and cultural facilities – many of them seemingly targeted for their heritage value and place in Ukrainian national identity.

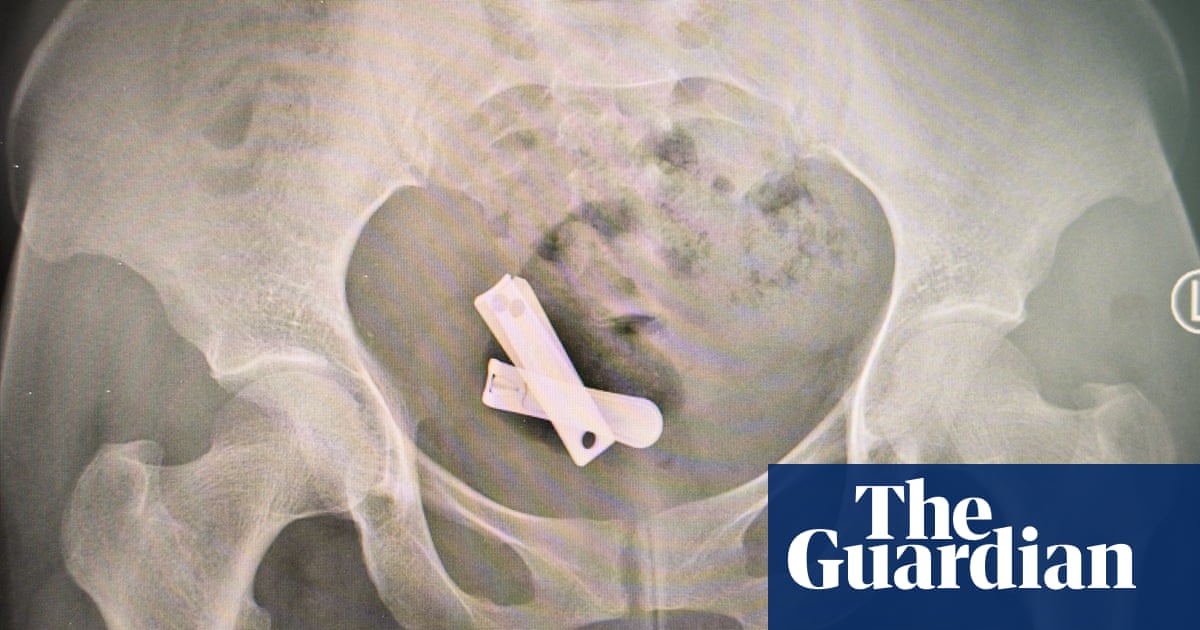

The Derzhprom building, despite being located several miles from the battlefield, was hit by a guided bomb on 28 October 2024. The complex, which was on Unesco’s tentative list for world heritage status, had already suffered collateral damage from attacks on Freedom Square, by Russian cruise missile strikes in March 2022 and a kamikaze drone attack in January 2024. But the October strike was from a precisely guided rocket, which destroyed one of the sections of the building, damaging the roof, exterior walls, floor slabs and windows.

The choice of target was no accident. Despite being of notionally Russian origin – having been designed in then Leningrad (although by architects who hailed from Ukraine’s major port city, Odesa, and Vilnius, in Lithuania) – the Derzhprom building had always symbolised the autonomy of Kharkiv. It was a monument to the roaring 20s in Ukraine’s then capital, built at a time when the city was alive with avant-garde writers, composers, artists and architects. It was a golden age, when Kharkiv was one of the most significant industrial, cultural, scientific and educational centres of the USSR, a period that left a lasting, if often overlooked, built legacy.

The Railway Workers Palace of Culture is another constructivist gem from the era. Designed by Aleksandr Dmitriev, and built from 1927 to 1932, its gently scalloped facade has an elegant art deco air, like a giant accordion being stretched open. It housed a huge concert hall, library, exhibition spaces and dance hall, which hosted dozens of amateur art, music and dance clubs, where railway workers and their families could develop their talents and spend time together. Still in the ownership of the railway company, it was recently restored, and most of its original interiors had remained intact. That is, until March 2022, when a Russian missile attack destroyed most of its windows. A second strike in August that year caused further structural damage, leading to the collapse of the concert hall ceiling, and the loss of most of the interiors to fire.

Gubkina’s book doesn’t dwell on the destruction. “I was so tired of the stereotypes,” she says. “People only see us connected with rubble and war. Yes, Russia has destroyed a lot, but my mission is to show what a rich and resilient place Kharkiv is.”

The sheer variety of riches makes the book a visual treat, even from the armchair. Marvel at the gilded onion domes of the Assumption Cathedral, or the expressionist granite torsos that hold up the Kupetskyi bank and hotel. Gawp at the daring barrel-vaulted roof of the 1960s Ukraina cinema and concert hall, or the cantilevered limestone forms of the brutalist state opera and ballet theatre – a herculean construction project, begun in 1967 and only completed in 1991. It is one of the few venues in the city that has remained operational while under siege, given that one of its auditoriums is essentially housed in an underground bunker. “It sometimes feels surreal that you can visit a beautiful piano jazz concert in the middle of war,” says Gubkina. “But that’s what gives us hope.”

Other buildings haven’t been so lucky. The scale of devastation is brought home in a powerful series of photographs, taken by Pavlo Dorohoi in March 2022, inserted at the beginning of the book. The architectural photographer had been commissioned to shoot a number of sites for the publication, but unexpectedly found himself reporting from the frontline of a war zone, before international press photographers had made it there. One image shows the bombed-out courtyard of the Palace of Labour, originally built in 1916 as the House of Rossiya Insurance Company, but barely occupied before the Bolshevik revolution. “It is ironic that the building is named after Russia,” says Gubkina, “and Russia decided to destroy it.”

She returned there last summer, for the first time since the invasion began. “It was the first moment when I really started crying in Kharkiv. I remembered the complex as a very vibrant place from my childhood, with courtyards full of cafes. Now it was a ruined shell.”

Gubkina winces when I raise the talk of reconstruction plans. In April 2022, just a couple of months after the first missiles were launched, Norman Foster offered his services to the mayor of Kharkiv. The architect lord had been working on several projects in Russia up until the invasion, but he quickly severed ties, and hastily launched his Manifesto for Kharkiv that pledged to “assemble the best minds in the world” to tackle the “rebirth” of the city.

The ensuing masterplan, published by the Norman Foster Foundation in December 2023, called for “a new iconic architectural landmark” as well as “an iconic, revolutionary mixed-use neighbourhood, dedicated to promoting scientific and technological innovation”. Claims of local engagement and public consultation have been somewhat undermined by the fact that detailed information about the masterplan is only available in English – a language that only a small proportion of the Ukrainian population can understand.

“I think it is strange to build your fantasies about people’s needs, without ever asking them what they really want,” says Gubkina. “People need their buildings to be repaired, so they can return to this city. I don’t think they need beautiful fantasies about iconic glass skyscrapers.”

Other Ukrainian architects have been just as wary of Foster’s involvement. Oleg Drozdov, co-founder of the Kharkiv School of Architecture, has warned of the risks of “intellectual colonisation”, while his colleague Iryna Matsevko is concerned by “copy-paste” masterplanning. Urban planning researcher Olexiy Pedosenko has been critical of the lack of transparency and meaningful consultation. “The message to Kharkivites seems to be: ‘We have decided an overarching trajectory without you, but maybe in the upcoming phases, we might consult you,’” says Pedosenko. “Ukraine is full of expertise, and it deserves better.”

Gubkina is frank about the more pressing matters at hand. “I’m not sure that a futuristic vision for Kharkiv as a centre of innovation for worldwide enterprises is the right way to spend money,” she says. “We have a lot of fragile heritage to save and repair right now, and some conservation would be great.”

-

Architectural Guide: Kharkiv is out now as part of the Histories of Ukrainian Architecture programme initiated by DOM publishers in response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine’s sovereignty on 24 February 2022

3 months ago

46

3 months ago

46