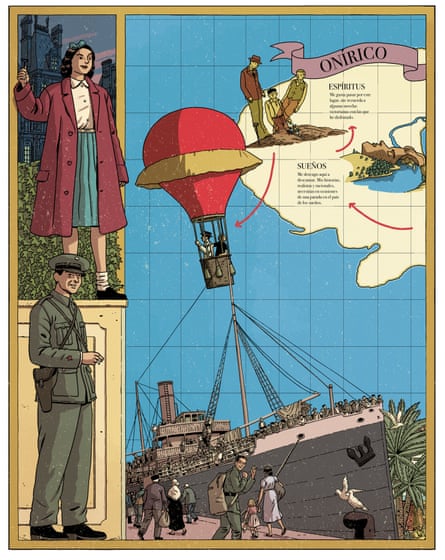

The map of Paco Roca’s mind, a landscape of memory and loss, unfolds across the walls of an exhibition hall in Madrid, inviting visitors to acquaint themselves with the bittersweet geographies that have shaped the work of one of Spain’s best-known graphic artists.

Roca, whose comics have explored such varied themes as Francoist reprisals, the exiled Spanish republicans who helped liberate Paris from the Nazis, family histories and the depredations of Alzheimer’s, is the subject of a new show called Memory: An Emotional Journey Through the Comics of Paco Roca.

Staged as part of a year-long programme of events to mark the 50th anniversary of the death of Franco and Spain’s subsequent return to democracy, the exhibition looks at how the 56-year-old artist has recovered, preserved and shared memories and testimonies.

“The idea was to make it all look like an encyclopaedia or a set of Victorian maps because, as the end of the day, it’s an atlas – a collection of maps that chronicle the journey of creating a comic,” said Roca.

“There are three panels about memory: historical memory; memory and identity; and family memory. The maps try to show what’s involved in the creation of any artistic work, whether it’s a comic or a film or a novel.”

Given the subject matter and Roca’s own approach to trekking after the past, the peripatetic, cartographical and non-linear nature of the exhibition seemed only fitting. Its four murals, 19 annotated strips and dozens of sketches, photos and reference points – from lighthouses and hot-air balloons to Jules Verne, Gustave Doré and Hergé – form part of a meandering trail.

“The author never goes in a straight line from the initial idea to the final result, trying to do things as efficiently as possible,” he said. “That’s what AI might do. The author is after an emotional tour.”

Although memory is the thread that runs through all Roca’s work, some of his most famous journeys have led him into the still controversial realms of historical memory. His most recent book, The Abyss of Forgetting, co-written with the journalist Rodrigo Terrasa, is about a woman’s struggle to find remains of her father, who was murdered after the Spanish civil war ended.

“Reconstructing the testimonies of people who couldn’t talk about things when they were happening – for different reasons – is a creative and personal challenge,” he said. “People were repressed into silence during the dictatorship and they couldn’t talk about the tragedies in their lives for 40 years. And it’s even complicated in democracy because as soon as somebody talks about something that happened, you get these voices saying: ‘Come on! What do you want to remember all that for?’”

Roca is also driven to use those testimonies to create a visual memory where none exist.

“Unlike what happened after the second world war in Europe, where there were visual records of the horror – the first thing the allies did after liberating the extermination camps was take photos of them and film them, so that only a handful of idiots can deny the horrors of fascism – there wasn’t a visual memory in Spain,” he said.

“We don’t have photos of the prisons and the executions and the repression and the mass graves. It can be really hard to draw because you often don’t get a lot of detail from the testimonies because they’re inherited memories, passed from parents to their children. But trying to contribute to the creation of this visual memory of that horror is really important to me. Hearing a testimony isn’t the same as seeing it drawn.”

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Roca reflects on how he has used his own family history to delve into Spain’s past – and on how those stories have ended up becoming something more universal.

“The thing that really interested me about my family and its past is that they’re totally normal people whose early lives were marked by the misery and the hunger of the postwar period,” he said. “But the books I’ve written about them have been published in a lot of countries, and that makes you realise that they’re not just everyday stories about Spain; they’re also stories about grief and memory and nostalgia.”

Questions about how memory shapes us recur in the section that examines recollection and identity. As well as looking at how age and disease “can wipe both our memories and our identities”, it features Marjane Satrapi, whose Woman, Life, Freedom – a collective work by 17 Iranian and international comic book artists, including Roca – showed how women have defended their identities amid the repression of the Iranian regime.

Roca is well aware that sections of the Spanish right are unhappy with the notion of a year of celebrations to mark the end of the dictator. He also knows that some have accused Spain’s socialist-led government – whose democratic memory ministry has organised the exhibition in partnership with the Instituto Cervantes – of playing politics with the past.

But then political polarisation, he added, was hardly a problem unique to Spain.

“In Germany, you have parties that are questioning things that everyone had thought had been settled and you have these nationalist movements erupting in Europe and the US and you have [Javier] Milei attacking historical memory in Argentina,” said Roca. “It’s a bad time for society, but it allows authors to reflect on this and to find stories that had been consigned to oblivion.”

And that, said the artist, was what it was all about: the odd individual trying to give the voices of the past a decent, if belated, hearing. It can sometimes be a lonely business – and solitude is another of the exhibition’s themes.

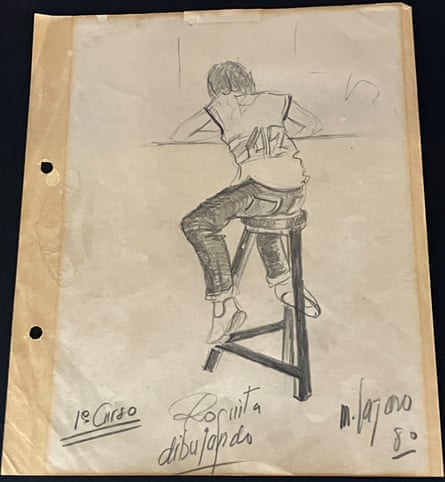

Roca pointed to a glass-topped cabinet that held an old pencil drawing of a boy in jeans and a T-shirt crouching over a desk. “I found this sketch that my drawing teacher did of me in 1980,” he said. “I’m still in that same position, alone and hunched over a piece of paper.”

3 months ago

38

3 months ago

38