If you’re at all familiar with contemporary Latin American photography, you’ve probably encountered the unforgettable image of a Zapotec woman crowned with live iguanas, radiating quiet, unshakable dignity. Captured in 1979 by Graciela Iturbide, Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas, Juchitán was neither planned nor staged. It was taken on impulse, guided by the artist’s instinct and deep respect for her subject, and has since become a touchstone of Mexican visual culture and feminist photography.

“What drives my work is surprise, wonder, dreams, and imagination,” Iturbide recently told the Guardian.

Indeed, surprise has been the animating force behind her entire career. Born in 1942 in Mexico City, Iturbide was in her late 20s, married and raising three children, when she heard a radio ad for the Center for Cinematographic Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de México. On a whim, she applied and, under the mentorship of the legendary photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo, began a journey that would establish her as one of Latin America’s most revered photographers.

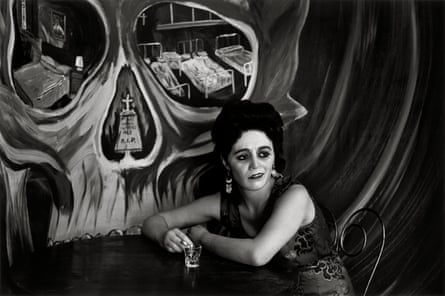

Iturbide’s images inhabit the space between document and dream. They are grounded in reality yet imbued with poetic sensibility, revealing the mysteries of everyday life. Her most celebrated works capture the spirit of communal life and Indigenous traditions in Mexico, while her series taken abroad in countries such as Cuba, India, Argentina, and the United States also hold a significant place within her vast body of work. At 83, Iturbide remains a vital force in photography, she’s been the recipient of the Hasselblad and the William Klein Award, and earlier this year she was honored with the Premio Princesa de Asturias.

Until January 2026, the International Center of Photography in New York will present Graciela Iturbide: Serious Play, a career-spanning exhibition of nearly two hundred works drawn from Fundación MAPFRE’s extensive collection. The show offers a rare opportunity to experience the full breadth of her vision — from early portraits to later meditations on landscape — most rendered in black and white, the visual language she has embraced since her formative years studying with Álvarez Bravo.

“Color feels unreal to me,” Iturbide said. “I work in black and white, I dream in black and white, I photograph in black and white because it is an abstraction of everything.”

Far from monotonous, her monochrome images pulse with depth and soul, the result of an intimate and immersive approach. To document Indigenous communities, Iturbide has lived among her subjects, participated in their daily routines and rituals, and built trust over months and sometimes years, as she did while creating her lauded book of photographs Juchitán de las Mujeres (1979–86), to which she dedicated nearly a decade.

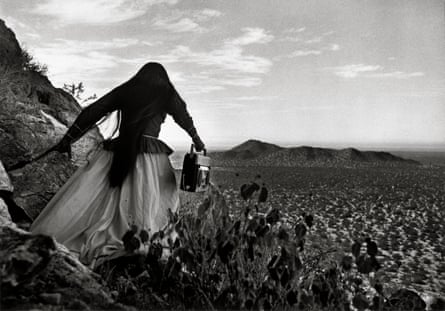

In 1978, a commission from Mexico’s National Indigenous Institute took Iturbide to the Sonoran Desert, where she photographed the Seri people, nomadic fishermen striving to preserve their ancestral traditions. From this project emerged Mujer Ángel, Desierto de Sonora, México (1979), a photograph, on show at the ICP, which the artist describes as a gift from the desert itself, as she can’t recall the exact moment she captured it, a testament to the profound and intuitive relationship she maintains with the places and people she photographs.

While various elements of Indigenous Mexican communities, their rituals and festivals, flora and fauna, and sweeping landscapes, feature prominently in Iturbide’s oeuvre, portraits of women, such as Vendedora de zácate, Oaxaca, México (1974), have remained a central and resonant focus throughout her practice.

“Do you know why my photos of women have traveled the world? Because I’ve lived with them, gone to the market, sold jitomates with them, and slept in their houses. They become my collaborators. It’s my way of creating camaraderie, a sense of complicity,” she explains. “I always photograph with the consent and collaboration of the people.”

The iconic portrait of the woman crowned with iguanas also emerged from this approach. “I would sit with the women at the market so they could get to know me, and I would accompany them to sell their chickens and iguanas,” Iturbide recalled. “All of a sudden, I saw this woman carrying live iguanas on her head and asked to photograph her. I only had one roll of film, and of the twelve frames I took, all were in motion and she was laughing, except one, which captured her dignity. Now there is a large sculpture of her in a plaza in Juchitán, where countless political demonstrations take place. They’ve made small clay figurines of her, embroidered her image on huipiles, and she even appears in murals in Los Angeles and San Francisco. This photo didn’t ask for my permission; she wants to soar, and that’s fine, it’s fine that she goes wherever she wants.”

While spontaneity plays a central role in Iturbide’s practice, her work is also rooted in careful preparation and respect for the people and cultures she photographs. “I never work with scripts. I only capture what emerges by surprise, that is, what my eyes see and my heart feels, but I always read extensively about the places I’m visiting and I speak with the elders so they can share their stories and gradually help me form my understanding of their culture,” she explained.

This balance between intuition and intention extends into her studio, where developing film unfolds as a quiet ritual. “After photographing, I return home. I still work with film: I develop it, review the contact sheets, and organize them. For me, it is a ritual, arriving, examining my negatives, and selecting them,” she said. This deliberate process mirrors the contemplative nature of her images, revealing the reverence at the core of her practice.

Iturbide’s self-portraits, several of which will be on view at the ICP, also arise from her instinctive impulse. “I never prepare my self-portraits; it’s something that happens in the moment, usually when I’m in a bit of a crisis,” she explained. “For instance, in Eyes to Fly With?, Coyoacán, Mexico (1991), a hummingbird had come into my house and died. I was in a crisis, wondering if I would continue photographing, so I quickly went to the market, bought a live one, and placed both on my eyes, all in a very unconscious way.”

In recent years, as security concerns have made photographing in Mexico’s rural towns increasingly difficult, Iturbide’s focus has further shifted beyond Indigenous communities to include landscapes, nature, and broader reflections on humanity across different countries. “In some ways, I think I’m now turning my attention to the origin of humankind,” she said. Still, her practice remains as spontaneous and heart-centered as ever. “I may be wrong, but I don’t have rules,” she said. “Working with my heart is the only rule – nothing else.”

-

Graciela Iturbide: Serious Play is on display at the International Center of Photography in New York until 12 January

3 months ago

50

3 months ago

50