Leaves

A frail and tenuous mist on baffled and intricate branches;

Little gilt leaves are still, for quietness holds every bough;

Pools in the muddy road slumber, reflecting indifferent stars;

Steeped in the loveliness of moonlight is earth, and the valleys,

Brimmed up with quiet shadow, with a mist of sleep.

But afar on the horizon rise great pulses of light,

The hammering of guns, wrestling, locked in conflict

Like brute, stone gods of old struggling confusedly;

Then overhead purrs a shell, and our heavies

Answer, with sudden clapping bruits of sound,

Loosening our shells that stream whining and whimpering precipitately,

Hounding through air athirst for blood.

And the little gilt leaves

Flicker in falling like waifs and flakes of flame.

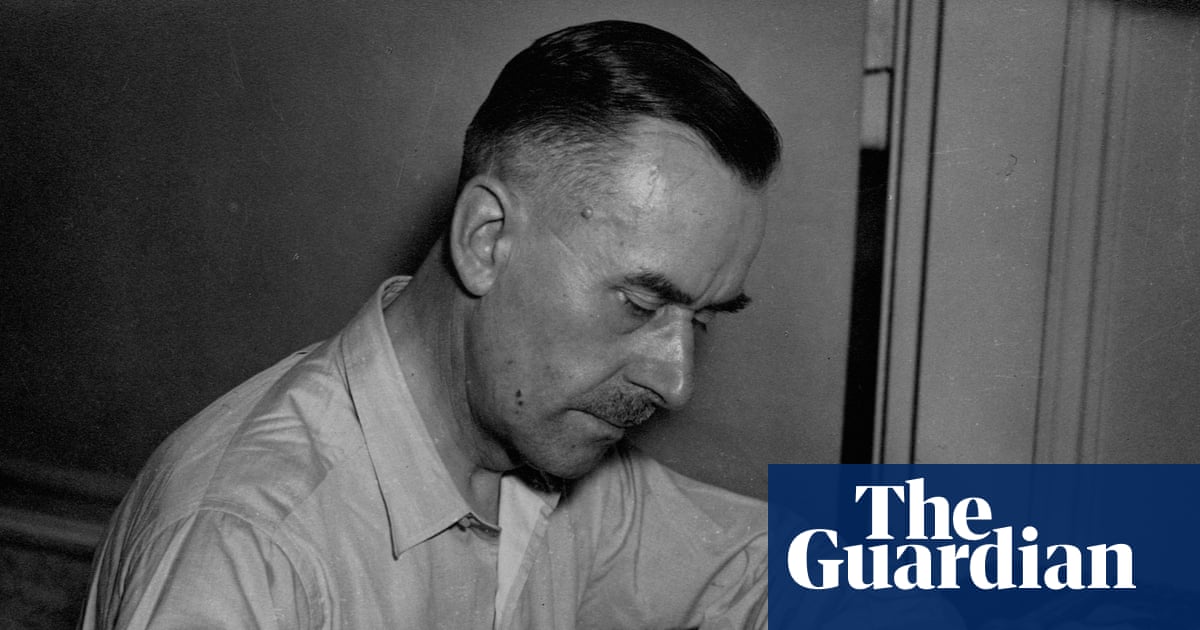

The author of this week’s poem, the Sydney-born Australian Frederic Manning (1882-1935), is considered to have written one of the best first world war novels ever published. He was 32 when war was declared. Living in England at the time, he enlisted in the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in 1915, having been rejected several times through lack of medical fitness. He had always suffered from respiratory problems and generally delicate health.

He failed an officer training course, but went on to fight with the 7th Battalion, and took part in the battles of the Somme and Ancre. His novel, lauded by Ernest Hemingway among others, The Middle Parts of Fortune, was published in 1929.

Manning’s experiences of trench warfare also inform his best poems. His contact with Ezra Pound, whom he first met in London around 1909, had a further decisive effect on his poetic technique. These war poems, Leaves among them, form the first and most interesting part of his second collection, Eidola (1917). Even the title, meaning “phantoms” or “idols”, has a Poundian undertone. The entire collection can be read here.

Leaves is a good example of Manning’s adaptations to the imagist style guide. It’s elaborate beyond imagism’s usual spare parameters but, despite the poem’s many pictorial figures and effects, the “little gilt leaves” in the second and 13th lines are an unforgettably defining image, singled out with a particular sense of exact visual weight.

The leaves are unexceptional, perhaps, as they hang motionless in the deceptive pre-battle calm of the opening stanza. In the couplet, where the sudden two-beat line repeats and isolates the image with a new definite article (“the little gilt leaves”) something almost uncanny occurs. The leaves are falling but it’s not a natural, autumnal process; they’ve been loosened by the reverberation of “our heavies” (heavy weapons) with their “sudden clapping bruits of sound”. Admittedly, the last phrase is a tautology, but if the pronunciation of “bruits” is anglicised, as I think it should be, it heightens the impact of the adjective, “brute”, in the third line of the second verse. The final view of the leaves “like waifs and flakes of flame” doesn’t seem overwritten: the visual transformation of the leaves by the fire and firing creates further significant visual effects.

The poem’s first line is arresting. Its two pairs of adjectives, shared between the mist and the branches, are made to work as a team, as if a thread of understanding existed between the “frail and tenuous mist” and the “baffled and intricate branches”. The word “baffled” suggests a natural life-form puzzled by warfare’s unnatural lights and noises, and also associates, in sound, with the muffling quality of the mist. The stars are perhaps predictably “indifferent”, but the characteristic is important in the small drama of unawareness characterising the scene – the somnolent puddles, the deeper woodland and the “valleys, / Brimmed up with quiet shadow, with a mist of sleep”. Perhaps the human actors who set the forces of war in motion without full consciousness of their devastating power are implicated. The poeticism of the the earth “steeped in the loveliness of moonlight” is almost absorbed into Manning’s overriding sense of the illusory peace that’s about to be shattered.

As an unrhymed and somewhat experimental sonnet, Leaves is balanced in three sections. There’s a “turn” occurring after the five-lined first stanza , and Manning handles the change of mood and scene in the following seven-line block without loss of eloquence. Its opening is clear and dramatic. The simile Manning finds for the “hammering” guns – the “brute, stone gods of old struggling confusedly” – remembers and gives hard new force to the earlier bafflement of the tree’s branches. Then there’s a change of figure, and the sounds of the shells evoke a pack of hunting-dogs, “that stream whining and whimpering precipitately, / Hounding through air athirst for blood”. The hounds in their impatience to kill are given a line that seems to strain the metrical leash, and the presence of “hounding” in an unusual intransitive form adds to the swift menace of the four-beat 12th line: “Hounding through air athirst for blood”. Anger at the English class system may well be intimated in that unavoidable association of hunting and abused social privilege.

Manning’s war service continued until early in 1918, when he resigned his commission as an officer. He was serving with the Royal Irish Regiment, perhaps motivated by loyalty to his parents, both of whom had Irish ancestry. He continued to write in various genres, including biography, and died in Hampstead, London, of the respiratory illnesses that had always relentlessly pursued him.

1 month ago

36

1 month ago

36