Amid the hustle of midtown Manhattan on Wednesday 11 May 2022, James Cromwell walked into Starbucks, glued his hand to a counter and complained about the surcharges on vegan milks. “When will you stop raking in huge profits while customers, animals and the environment suffer?” Cromwell boomed as fellow activists streamed the protest online.

But the insouciant patrons of Starbucks paid little heed. Perhaps they didn’t realise they were in the company of the tallest person ever nominated for an acting Oscar, deliverer of one of the best speeches in Succession, and the only actor to utter the words “star trek” in a Star Trek production. Police arrived to shut down the store.

“No one listened to me,” Cromwell muses three years later. “They would come in, hear me at the top of my lungs talking about what they were doing with these non-dairy creamers, and then they would go around to the far corner, get their order in and stand there looking at their cellphones. ‘It’s the end of the world, folks! It’s going to end! We have 15 minutes!’”

Undeterred, Cromwell remains one of Hollywood’s greatest actor-activists – or maybe activist-actors is more accurate. He marched against the Vietnam war, supported the Black Panthers and took part in civil disobedience protests over animal rights and the climate crisis. He has lost count of how many times he has been arrested, and has even spent time in prison.

But now, at 85, he could be seen as the avatar of a disillusioned generation that marched for peace abroad and progressive goals at home, only to see, in their twilight years, Donald Trump turn back the clock on abortion and many other gains.

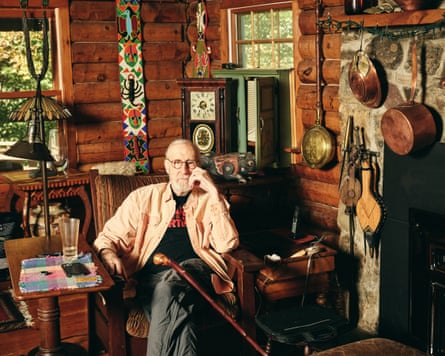

Cromwell certainly looks and sounds the part of an old lefty who might have a Che Guevara poster in the attic and consider Bernie Sanders to be too soft on capitalism. When the Guardian visits his home – a log cabin in the farming town of Warwick, upstate New York, where he lives with his third wife, the actor Anna Stuart – he rises from a chair at the hearth with a warm greeting and outstretched hand (it is a big hand that would have required a generous dollop of glue).

Cromwell stands at 6ft 7in tall like a great weathered oak. “Probably 10 years ago, I heard somebody smart say we’re already a fascist state,” he says. “We have turnkey fascism. The key is in the lock. All they have to do is the one thing to turn it and open Pandora’s box. Out will come every exception, every loophole that the Congress has written so assiduously into their legislation.”

Cromwell has seen this movie before. His father John Cromwell, a renowned Hollywood director and actor, was blacklisted during the McCarthy era of anti-communist witch-hunts merely for making comments at a party praising aspects of the Russian theatre system for nurturing young talent and contrasting it with the “used up” culture of Hollywood.

This seemingly innocuous observation, coupled with his presidency of the “Hollywood Democrats” which later “moved slightly to the left”, led to John Cromwell being called to testify to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He had nothing substantive to say but a committee emissary still demanded an apology.

John Cromwell refused and, with a $1m cheque from Howard Hughes for an unrealised project, moved to New York, where he acted in a play with Henry Fonda and won a Tony award. James reflects: “My father was not touched except for the fact that his best friends – a lot of them – cut him out and wouldn’t talk to him because he had been called to testify. They didn’t care whether the person was guilty or not – sort of like today.”

Cromwell’s mother, Kay Johnson, and his stepmother, Ruth Nelson, were also successful actors. Despite this deep lineage, he was initially reluctant to follow in their footsteps. “I resisted for as long as possible. I was going to be a mechanical engineer.”

However, a visit to Sweden, where his father was making a picture with Ingmar Bergman’s crew, proved to be a turning point. “They were creating something and my father was engaged and was working things out. It was very heady stuff for me. I said: ‘Oh, I gotta do this.’”

Art and politics collided again when he joined a theatre company founded by Black actors, and toured Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot for predominantly African American audiences in Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee and Georgia. Some performances took place under armed guard in case white supremacists tried to firebomb the theatre.

Godot struck a chord. At one performance in Indianola, Mississippi, the civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer urged the audience: “I want you to pay attention to this, because we’re not like these two men. We’re not waiting for anything. Nobody’s giving us anything – we’re taking what we need!”

Cromwell says: “I didn’t know anything about the deep south. I went down and the rooming house had a sign on the outside, ‘Coloreds only’. I thought: ‘That’s a historical marker, obviously, back from the civil war.’ A wonderful Black lady took us to our rooms.

“We went out to have dinner, and the owner of the restaurant came over and said: ‘You’ll have to leave.’ I’d never been thrown out of a restaurant before, so I immediately stood up with my fist balled. I would have done something stupid. John O’Neal [one of the company’s founders] informed the man that he was violating our civil rights and that they would get to the bottom of it.”

But then, mid-anecdote, Cromwell stops himself and breaks the fourth wall of our interview. “I’m listening to myself,” he says. “These are not just stories about an actor doing his thing growing up, trying to get the girl, trying to keep his nose clean, trying not to get hurt. People were dying, people were being beaten, people were being shot, people had crosses burned on their lawns.

“I feel strange recounting it always with the points that I think an interviewer would be interested in: ‘My story’. People ask if I should write a book because I have all these stories and I’ve done a lot of different things as well as acting.”

Later, his wife will confide that she is among those lobbying Cromwell to write a memoir. But he has little appetite for such a project, he insists, since he fears it would be formulaic and “because my father tried it and it was so bad even his wife, who adored him, said: ‘That’s really stinky, John.’”

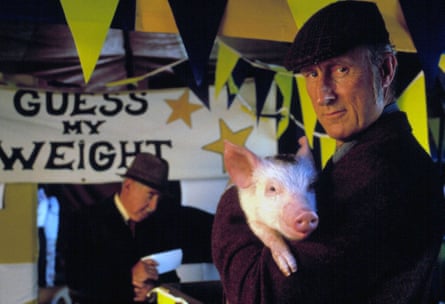

We push on with his story all the same. Cromwell had been notching up film and TV roles for decades when, at the age of 55, his career took off thanks to his role as a farmer in Babe, a 1995 film about a pig that yearns to be a sheepdog. It was a surprise hit, grossing more than $250m worldwide.

Cromwell funded his own campaign for an Oscar for best supporting actor in Babe, spending $60,000 to hire a publicist and buy trade press ads to promote his performance after the studio declined to fund it. The gamble paid off when he received the nomination, the kind of accolade that means an actor is offered scripts rather than having to trudge through auditions.

“I wouldn’t be here if I had not gotten a nomination,” he says, “because I was so sick of the dance that had to be done when you did an audition. I finally asked a director: ‘What was it about the audition that made you give me the part? I did it no differently than I’ve done anything.’ He said: ‘Jamie, it has nothing to do with your performance; we just want to see that you’re the kind of guy we want to spend four weeks with.’

“It was the chip on my shoulder which, because I knew him, didn’t show as much as it did when I went in to audition with a stranger who I identified as my father. I had the thing from my father – there he is again in me, telling me I’m not good enough, I’ll fail in the reading. I was just fucking sick of it.”

The recognition for Babe led to roles including presidents, popes and Prince Philip in Stephen Frears’ The Queen, as the industry tried to categorise him. In Star Trek: First Contact he played the spacefaring pioneer Dr Zefram Cochrane, who observes of the Starship Enterprise crew: “And you people, you’re all astronauts on … some kind of star trek.”

Cromwell views Hollywood as a “seamy” business driven by “greed” and “the bottom line”. He criticises the focus on “asses in the seats”, the lack of genuine debate on issues such as racial diversity and the increasing influence of online followings on casting decisions. He has “no interest in the parties” and sees the “game” as secondary to “the deal”. He also admits that he can be a handful on set: “I do a lot of arguing. I do too much yelling.”

He offers the example of LA Confidential, which he describes as a “genius piece of work”. In one scene, Cromwell’s menacing Captain Dudley Smith asks Kevin Spacey’s Jack Vincennes, “Have you a valediction, boyo?” before shooting him dead. Spacey, by then an Oscar winner, disagreed with director and co-writer Curtis Hanson over what Vincennes should reply. A quietly defiant Spacey won their battle of wills.

This spurred Cromwell to try a line change of his own. Hanson objected. “Sure enough, he stands behind me and says: ‘Jamie, I want you to say the line the way it was written.’ But not having Kevin’s experience and his propensities, I said: ‘You motherfucker, fuck you, you piece of shit! You don’t know what the fuck you’re doing.’ I kicked dirt on him. I punched a camera car.

“He had his arms crossed and he looked at me and said: ‘You asshole, I’m going to cut it out in post [production] anyway – it’s not going to be in there and you’ll never work in this town again.’ I learned: ‘Oh shit, you’d better perfect this technique because they’re not necessarily going to like this.’”

Thirty years on, of course, it is Spacey who has been banished to the Hollywood wilderness over sexual misconduct allegations, though he was not convicted of any crimes. Actors such as Stephen Fry, Liam Neeson and Sharon Stone have argued that Spacey paid the price and that unproven allegations should not permanently end his career.

Asked for his take, Cromwell at first demurs. “No, I can’t do that, man,” he protests. “I can’t talk about a fellow actor.”

But then he brings up the late financier Jeffrey Epstein, suggesting that the convicted sex offender’s elite social circle has received more lenient treatment than Spacey. “They have one set of rules for them and another set of rules for Kevin. Kevin gets whacked, it means the end of his career. They [the Epstein associates] all fly down there on their Lolita Express, they do whatever they want. What happens to them? Zilch happens to them. The justice department is turned upside down. That’s what pisses me off. The duplicity of it. It’s disgusting.”

In a varied TV career, Cromwell has won an Emmy award for American Horror Story: Asylum and earned Emmy nominations for roles in RKO 281, ER, Six Feet Under and most recently Succession where he played Ewan Roy, the estranged brother of the Rupert Murdoch-style patriarch Logan Roy (Brian Cox).

Cromwell spent an hour talking with Jesse Armstrong, creator of Succession, before agreeing to take on the role, insisting that Ewan Roy’s break from the family should be based on political morality rather than financial jealousy. “I figured out he was a Vietnam veteran. He went in for two tours. I said: ‘Nobody comes back from two tours in Vietnam unblemished, untouched by the havoc, the chaos of that place.’”

Cromwell adds, however, that Armstrong is a “smart” writer who managed to write around his objections and get him to play the character that Armstrong wanted. The arc culminated in a powerhouse eulogy delivered by Ewan at Logan’s funeral – a perfect marriage of the crafts of acting and writing.

Ewan’s formative experience in Vietnam was an inversion of Cromwell’s own political awakening as an anti-war protester. He was arrested for the first time at a huge demonstration in Washington in 1971. He recalls: “I took a swing at a cop because he hit this woman right in front of me, across the face with his baton, smashing her glasses, and I said: ‘That can’t be.’

“I grabbed him and came away with his baton, and then they all jumped on me, but nobody hurt me. As I was being loaded into a van, the cop I jumped came at me with his fist, he threw it and it glanced off me, and then they shut the door and nothing happened to me.”

There have been dozens of arrests since then. After a sit-in protest in 2015 at a natural-gas-fired power plant in Wawayanda, New York, Cromwell refused to pay a $375 fine and ended up in prison. “The guy who did the interview didn’t know who the fuck I was and said: ‘Are you afraid you’ll be raped when you’re in here?’ I said: ‘Not unless they’re a lot hornier than I think they are,’ because it didn’t make any sense.

“He said: ‘Are you afraid that you’ll rape someone?’ Will I catch the disease of the class system in prison in order to protect myself and put myself in a position of finding some defenceless young men sent in there for some reason, and get a couple of guys to hold him down while I fuck him? That’s the thinking.”

Cromwell describes his three days inside as “moving”. He went on hunger strike and had the poignant experience of seeing “Oh God, get me out of here” written in the grout by another inmate. Soon after, he was arrested again, this time for disrupting an orca show at SeaWorld.

He is a vegan and an honorary director of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta), which he calls “the most ethical organisation I have ever been involved with”. He insists that society must “stop killing animals, start creating vegan foods, which are nutritious, tasteful and don’t involve killing another animal”. He sees animal agriculture as a significant contributor to global heating, which “is going to kill us. It’s going to kill our children. It’s going to kill the planet”.

Cromwell got the Starbucks glue idea from Extinction Rebellion, the British-founded movement that aims to compel government action through non-violent civil disobedience. Extinction Rebellion’s road blockades, and the group Just Stop Oil’s attacks on artworks, have been criticised by some as counterproductive. He disagrees.

“If you don’t push back, they eat you alive,” he insists. “Now, is pushing back going to go to excess? Sometimes, yes. We’ve got crazies; we have double agents, we have people infiltrated. You think the East Germans, the communists had it? They don’t have anything to put up with compared to what we’ve got going on in this country as the ratline for taking people out, misinformation, throwing elections, buying elections. Every fucking thing that they can do, they do.”

But did he ever worry that activism would hurt his acting career? “I don’t think they give a shit what – no, I take that back. Enough people know me now because of my animal activism that the studio might consider I’m a troublemaker and, when it comes to the press junket, instead of talking about the movie I’m going to talk about veganism or Gaza.

“So the best way to shut him up is just to shun him, and that’s true for Will Geer [an actor and activist blacklisted during the McCarthy era] and that’s true for a lot of people who had something to say and wanted to say it, and could have been able to say it.”

In Cromwell’s worldview, the descent of the US into tyranny runs much deeper than one president. It is an amoral system designed to benefit oligarchs, exploit loopholes and grind down the working class and the planet. Trump is merely “the frontman”, he says.

“He’s the guy outside the theatre saying: ‘Come on in! You’re going to love this show, I got the best people.’ That’s who he is. He’s a shill for this shit. While Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and those guys walk around, they don’t give a rat’s ass about any worker, about any environmental issue. They don’t give a shit.

“The governmental system that we have, the societal system we have is so corrupt and so full of mendacious, egregious lies that it’s very hard to know how to look at it and say: ‘Well, what do I do?’”

Cromwell’s generation must have thought they had won significant battles for women’s rights, civil rights and the environment. Yet, now, in old age, they are forced to watch Trump and his allies unravel that progress. After all the years, all the protests, all the arrests, does he still have hope?

He cites students protesting at New York’s Columbia University, civilians protesting in Israel and a few American politicians who are still fighting the good fight. He also talks about his T-shirt, which is black and printed with the words “Dare to be an artist” in red.

He explains: “If celebrity is stuffed in your pocket, it burns a hole in your pocket. You have to spend celebrity so that people can learn something from it and they can hear you and you can speak for them. This is the advantage that I have that somebody in Texas does not have. You come and stick a microphone in front of me and it goes someplace and somebody listens to it.”

Starbucks, by the way, capitulated last year and announced that it will no longer charge extra for vegan milks. Cromwell was not shouting into the void after all.

3 months ago

45

3 months ago

45