The art world is obsessed with the idea of “being seen”. In a culture of lookism, being seen is understood as tantamount to existing, even to survival. But being seen is complicated. Both the current exhibitions at Autograph grapple with this through photographs by two women of the same generation working in portraiture.

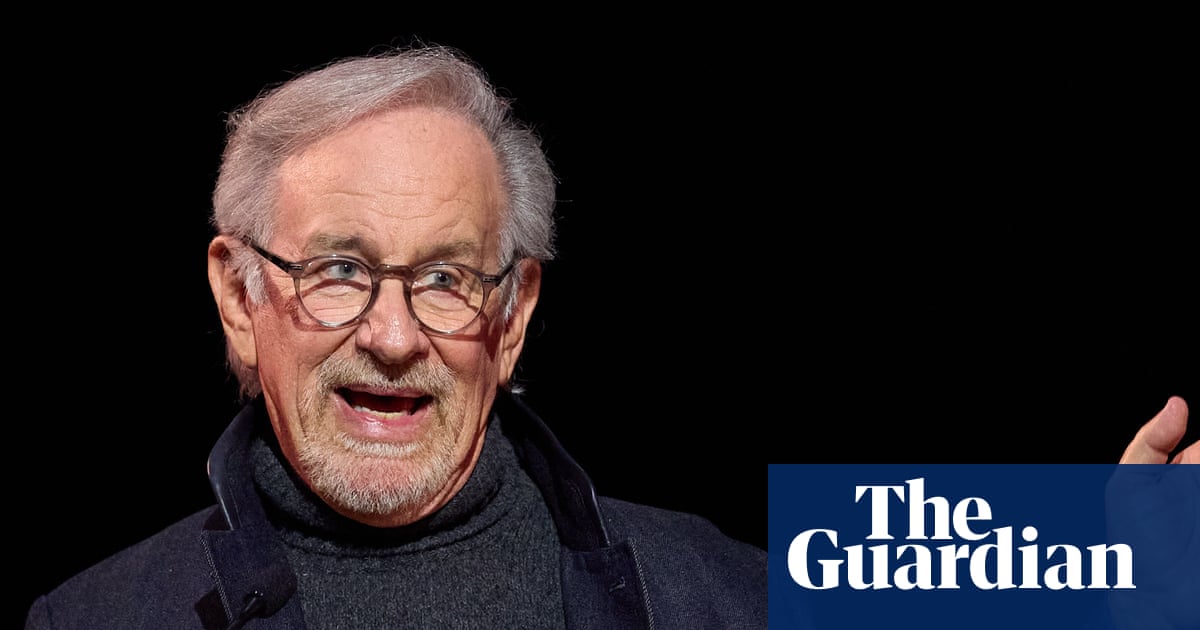

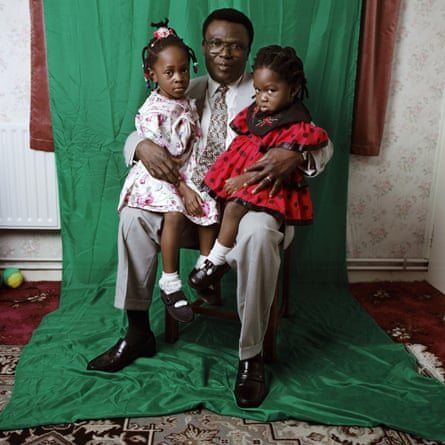

Eileen Perrier’s A Thousand Small Stories occupies the ground-floor gallery. Since the 1990s, Perrier’s work has centred on setting up temporary photographic studios, in homes, hair salons, on the streets of Brixton and Peckham in London, and at a metro station in Paris. Her 2009 exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London displayed large-format Polaroid portraits taken in pop-up studios at Petticoat Lane market and in the nearby 23-storey tower block Denning Point. The travelling portrait studio has been a device Perrier has used for 30 years, to take photography into diverse communities and tackle the politics of beauty and identity. This is the first survey of her work.

Perrier makes portraits that don’t rely on beauty but find it everywhere. She doesn’t flatter – in fact the lighting and poses in her pictures in some series are direct references to school photographs, such as Grace (2000) in which her subjects, including the photographer and her mother, share the physical trait diastema (a gap between the teeth). Perrier’s subjects are mostly regular people, commuters, passersby. In these quick encounters with ordinary lives, Perrier gives glimpses of beauty where you don’t look for it.

An image of two women on a leather chesterfield, from the series Red, Gold and Green (made between 1996 and 1997 in the homes of three generations of British Ghanaians), scintillates with shining confidence, from the women’s style to the polished ceramics gleaming on the dresser behind them. The makeshift red cloth Perrier has hung up behind them is a reminder that this is a studio, too, where an unexpected moment of beauty, through the alchemy of the camera, becomes an eternity.

There’s an unresolved paradox in Perrier’s pictures, between the artifice of beauty and the photographer’s constant quest to find it. Perrier acknowledges this, between celebrating beauty and critiquing it, right from the start of her career. One of the earliest works in the show belongs to her documentary portrait series, Afro Hair and Beauty Show. Between 1998 and 2003, Perrier photographed women attending the annual show at Alexandra Palace, one of the venue’s biggest events of the time.

It’s a document of evolving styles, creativity and the importance of self-expression through hair. While making the portraits, Perrier also began collecting and photographing products for black hair and skin from London shops and photographing them. She turned these grooming goods into a wallpaper that also charts a controversial side of the beauty industry: Dear Heart promises skin lightening, hair relaxant for children is marketed as Beautiful Beginnings.

Perrier is positioned through this show as an important counter to a Photoshopped, retouched reality, in a culture of beauty and image worship. Upstairs Dianne Minnicucci’s small exhibition of new works – made as part of a residency funded by Autograph – picks up on the impact of white-centric beauty standards on women of colour. Minnicucci confesses to not being comfortable in front of the camera herself – she has portrayed her family and domestic scenes with an intimate, autobiographical tenor but had never ventured in front of the lens herself.

Her show, Belonging and Beyond, is about a personal struggle with self-image, compounded by photography, and now using photography as a means to unravel and understand it. Like Perrier, Minnicucci began by dismantling and reconstructing her studio – bringing it into the classroom of Thomas Tallis school, south-east London, where she is head of photography. Working alongside her students for six months, inviting them into the work as collaborators, Minnicucci was forced to practise what she’d preached – to embrace discomfort.

A series of wistful black and white self-portraits sees Minnicucci try to break through this awkward confrontation, all of them shot in Lesnes Abbey Woods. We see her figuring out what to do with her body, her hands, her gaze. Half-masked by spiky shrubs and trees, thesepictures have a quiet, self-conscious grace. Minnicucci dressed in white in this misty atmosphere looks shyly away from the camera, tentative, uncertain. This is not really about the images but what the process reveals. In a film accompanying the images, Minnicucci realises where her trepidation in taking self-portraits as a black woman might come from: “Because I haven’t been exposed to those images, maybe that’s why?”

3 months ago

79

3 months ago

79