Seventeen centuries after they last burned, a handful of broken oil lamps could shed light on a small and long-vanished Jewish community that lived in southern Spain in the late Roman era as the old gods were being snuffed out by Christianity.

Archaeologists excavating the Ibero-Roman town of Cástulo, whose ruins lie near the present-day Andalucían town of Linares, have uncovered evidence of an apparent Jewish presence there in the late fourth or early fifth century AD.

As well as three fragments of oil lamps decorated with menorahs and a roof tile bearing a five-branched menorah, they have also come across a piece of the lid of a cone-shaped jar bearing a Hebrew graffito. While experts are split over whether the engraving reads “light of forgiveness” or “Song to David”, its very existence points to a previously unknown Jewish population in the town, which eventually fell into decay and abandonment 1,000 years later.

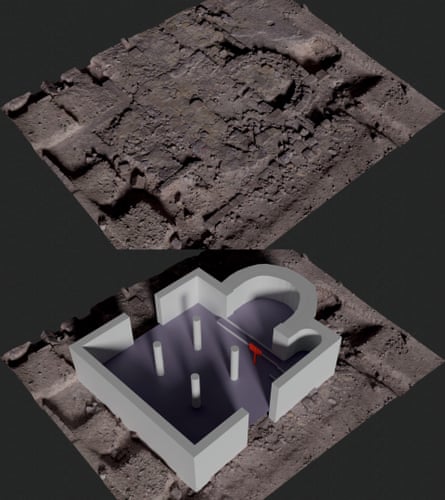

The discovery of the materials has led the team to consider whether the ruins of a nearby building, assumed to be an early Christian basilica dating from the fourth century AD, could perhaps have been a synagogue where Cástulo’s Jewish community came to worship.

When the site of the supposed church was first excavated between 1985 and 1991, archaeologists assumed it was a Christian edifice. “During the 2012-2013 [dig], we found the roof tile with the five-armed [menorah],” said Bautista Ceprían, one of the archaeologists working on the Andalucían regional government’s Cástulo Sefarad, Primera Luz project, which aims to uncover the town’s Jewish history. “Until that moment, we didn’t know that there could have been a very small Jewish community in Cástulo.”

In a recently published paper, Ceprián and his colleagues David Expósito Mangas and José Carlos Ortega Díez consider the possibility that the “church” could in fact have been a synagogue.

They argue that the lack of Christian materials in the site, combined with an absence of evidence of burials or religious relics – which would normally be expected in a Christian church of the era – could point to its use as a Jewish temple. A nearby baptistry, in contrast, has already yielded Christian finds and burials. Jewish religious law, however, forbids burials within 50 cubits (23m) of a residential area.

“When we looked at the interior of the building a little more closely, there were some strange things for a church; there was something that could have been the hole for a big menorah,” said Ceprián. “It’s also strange that this building doesn’t have any tombs.”

The authors also point to the site’s architectural features, such as its layout, which is reminiscent of some synagogues found in Palestine.

“Synagogues of that time could be more square in shape than Christian basilicas because in Jewish worship, there’s usually a central bimah [raised platform], which people sit around,” said Ceprián. “In a church, the priest performs the rituals in the apse, which means things are more rectangular.”

Then there is the location of the possible synagogue; it would have sat in an isolated part of town near a ruined Roman bathhouse that would have been feared and hated by the local bishops.

after newsletter promotion

“The Roman baths were the last pagan place that remained in a city,” said Ceprián. “It was something diabolical and therefore something that had to be outside the Christian world. It seems to be the case that the baths in Cástulo had already been closed by the end of the fourth century, or the beginning of the fifth century.”

He argues that the synagogue’s location, so close to a font of paganism, would have helped the local Christian hierarchy in its efforts to conflate Judaism with unholy practices: “The Jews would have had few options and at that moment it’s clear that it’s the bishops who are fundamentally organising the town – and it would allow them to relate Jews with evil.”

If the researchers’ theories were to be confirmed, the Cástulo synagogue would be among the very oldest Jewish temples on the Iberia peninsula. Spain’s handful of surviving original synagogues are mainly medieval. The most recently discovered synagogue, in the Andalucían city of Utrera, dates from the 1300s.

The problem for Ceprián and his colleagues – as they acknowledge – is the lack of written historical corroboration. “I’m sure there will be criticism, which is totally legitimate – that’s how science works and how it has to work,” he said. “But of course we believe we’ve provided data with enough seriousness to allow ourselves to posit it.”

Whether the building was a church or a synagogue, those digging up Cástulo have uncovered evidence of what would appear to be a small Jewish community living, if only for a while, in peaceful coexistence with their Christian neighbours. As the centuries wore on and the church propagated the otherness of Spain’s Jewish inhabitants in order to forge and galvanise a Christian identity, there were pogroms and, finally, the expulsion of the country’s Jewish population in 1492.

“It shows us that there was a good coexistence between all the different social groups or faith groups that were there at that time,” said Ceprián. “But later, from the time when the Christian church begins to grow stronger in the Roman government, you start to get powerful groups opposed to those who are weaker in society. Oddly, that’s something that’s happening now, too.”

3 months ago

52

3 months ago

52