Matteo Haitzmann is a violinist who has tonight swapped his strings and bow for a skipping rope. With drummer Judith Schwarz and Arthur Fussy on modular synthesiser, he has formed an unorthodox trio to deliver a show in which each stroke, beat and jump lives up the title: Make It Count. It’s an hour of unusual rigour with an electrifying thrill – and the standout from my whirl through Vienna’s ImPulsTanz festival, a kaleidoscopic programme of performance and participation.

With the studied nonchalance of a rock star, Haitzmann stands on one of three island-like platforms, swinging what could be mistaken for a mic lead. Hanna Kritten Tangsoo’s lighting design will become increasingly mercurial but right now the synth desk twinkles, beams crisscross the stage creating an anarchic A next to the drum kit and the swirling rope resembles a red flash of lightning.

The surface of Haitzmann’s stage becomes a drum skin and the rope’s handle a substitute stick to build rhythm, each thud ushering in a sound that suggests the crack of a glacier. The musicians, wearing similar mottled outfits, pick up each other’s prompts and the sound swells until you can’t always identify each instrument. That’s because Haitzmann is now jumping feverishly and will spend most of the performance skipping: the swish and squeak of his exercise interrupted with an occasional yelp to cue a switch in lighting.

This is an incredibly disciplined piece, more so than much gig theatre, and the tempo slows for an erotically charged sequence in which the rope steadily thwacks the floor against the sultry pulse of the accompaniment. Haitzmann may look like a boxer in training but the difference is this is not an individual endeavour – he wants to get in the zone but bring everyone else in the room with him.

The intensity builds, punctured by Haitzmann’s occasional break for a snack or drink. A feat like this could easily come across as larky or po-faced but the design, music and movement are wholly integrated even in more delicately handled sequences, which retain an air of rehearsal experiments, where upturned cymbals are placed around the stage and struck with the rope. It all amounts to the most imaginative reframing of a music gig since KlangHaus stormed the Edinburgh fringe in 2014.

Part of ImPulsTanz’s young choreographers’ series, called [8:tension], Make It Count is a tightrope of a show, which chimes with an observation at the start of festival veteran Joe Alegado’s latest creation. “Performing is a high-wire act,” says Alegado. “An act of courage!” That’s the kind of circus-barker spiel that more typically introduces acrobatic spectacle but his new choreography, prefaced by softly spoken reflections and a meditative projected film, is triumphantly unshowy.

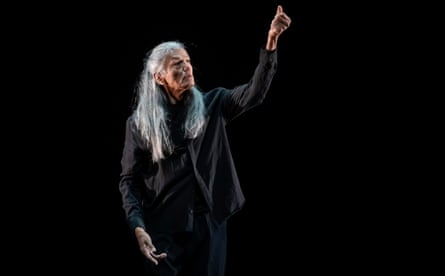

Alegado has been teaching workshops at ImPulsTanz since it was co-founded, 41 years ago, by Karl Regensburger (who still presides over the festival) and the late Ismael Ivo. Staged in a studio at Vienna’s Arsenal, a former military complex, under the unprepossessing title Bits and Pieces, Alegado’s offering captures what you could call the quality of sharing. On a barely lit stage, he begins with a graceful solo, the movement – especially the play of his fingers – often as wispy as his long grey hair. The piece ends with him pulling an imaginary thread; the next dancer arrives and resumes the motif.

One soloist inspires another soloist and they then join together in a duet; three individuals are in turn activated by another and led into a quartet. A playful sequence spotlights only the twisting hands of all four in a row (Alegado is joined by Blanka Flora Csasznyi, Simona Lazurová and Katarina Vinieskova), their black costumes concealing them in darkness. Throughout are gestures of giving and receiving, inspiring and developing, each move rounding out another’s idea to suggest the passing on of knowledge.

In the Arsenal’s warren of studios, workshops are doing just that, at all levels, with public classes ranging from dancehall to Limón technique, watched by anyone who chooses to linger. (The festival’s Public Moves programme has a series of open-air stages across the city for people to take part, too.) Alegado’s array of pieces have a similar openness; the voiceover, though portentous, discusses the challenge of being fully present on stage and in achieving timelessness in your work. That is done through the most minimal of means here; a simple caress or a glance are not nothing, the pieces suggest – they can prove long-lasting. In these fragments, Alegado evokes a stillness, no matter how busy the movement or the accompaniment, which at one point consists of a cacophonous layered looping of breath work. When the 45 minutes are up, the parting gesture is of thread being wound up, ready for the next time.

Bits and Pieces could just as easily provide an alternative title for the [8:tension] show Poor Guy, performed at the Schauspielhaus by Luigi Guerrieri, not least because he is fully naked throughout, save for jewellery from both the “Gypsy and non-Gypsy” sides of his family. Guerrieri explores how and when the sharing of personal trauma tips into narcissism or is met with kudos – whether it’s done on or off stage (and perhaps especially online, where the work originated). “I’m tired of myself,” he says, stretching out several octaves in that final word with look-at-me glee.

In these vignettes, the distinction between memoir and sketch can be unclear: was little Luigi really delivered by a firefighter, and made the fire department’s mascot? Amid the occasional dead-end routine, it’s certainly moving and very funny; Guerrieri has a sophisticated understanding of how humour can not just temper but elucidate the pain in his story. There is also some innovative vocal delivery from our wildly charismatic host despite a viral infection that has limited his range tonight.

He begins by massaging his nipples, as if milking his story for all it is worth. A family history of violence and instability emerges but he upends expectations of autobiographies, particularly “misery memoirs”, and unsettles the transaction between performer and audience, roaming the crowd and flattering us individually to seek our approval. If we pity Guerrieri, the show asks, does it empower him or us?

Against the same exposed brickwork of this stage, Greek choreographer Lenio Kaklea starts her double bill with Alegado-esque projections of dancing hands, fluttering like shadow puppet birds in her film An Alphabet for the Camera. Kaklea frames parts of her body using her fingers as a substitute viewfinder, before widening the lens to show her performing as a tiny figure lost in vast landscapes both natural and industrial (her silver coat merging into the greyscale of a warehouse). In such an environment, how do you express yourself?

Kaklea uses Madonna’s 80s hit of that name in the second piece, Untitled (Figures), performed on stage after an audio recording of Lesbian Nation author Jill Johnston. Kaklea has tremendous presence and first appears in bra and fishnets, responding to Madonna’s call to arms with finger clicks, smooth hips, coy glances, disco rolls and salsa shimmies before she struts down a chalked-out catwalk. But when the song is done, she deflates in a daze of confusion. It triggers a bid to express what she’s got – but on her own terms. Off come the bra and tights, on go side-buttoned jeans, boots and western hat but the techno score eventually leaves her on her back as if thrown from a horse.

Changing into a pale pink leotard, she shifts through a series of seated poses, maximising eye contact with the audience. A balletic sequence is then given a rodeo-rider swagger; her dissatisfaction returns, her poses now like a doll contorted into awkward positions. Next comes a nautical costume – a nod, perhaps, to another of her queer idols, the artist Yannis Tsarouchis. The show loses focus with her beguiling transformation as a lounge lizard, prowling around the audience with her tongue darting, but you’re left with the sense of a series of portraits in which Kaklea has searched for her own reflection.

In contrast to Guerrieri and Kaklea’s introspective solo pieces is the frenetic ensemble of Delirious Night, choreographed by Mette Ingvartsen, at the Akademietheater. It takes inspiration from the “dance epidemic” recorded in Strasbourg over several weeks in 1518, when people were gripped by a mania to keep dancing – some of them right until death. The hysteria is captured in a banner on stage: “Attitudes Passionelles.” But the febrile atmosphere that Ingvartsen captures is of our own Covid era: that strange combination of collective unity and fear, dissociation and division, the rumble of protest and the potential to rebuild. The stage fills with bodies seeking connection, the mood somewhere between campfire shindig and unruly protest. “How can I resist? I want to resist,” runs one refrain.

The dancers wear masks – Halloween ones, wrestling ones, beastly ones akin to Chewbacca – and many of them are topless, beating out rhythms on their bodies. There is no ringleader here, the paths pursued are freestyle and only occasionally do some of the nine performers fall into step. Ingvartsen captures that feeling of being out late, passing revellers, unsure whether they’ll prove to be jubilant or malevolent.

Drummer Will Guthrie drives the piece with his own feverish score, the movement becoming more jagged and incantatory, and some of the dancers seem to visibly age as they wearily group together and question how they can go on. You begin to feel the same as the vibe reaches an end-of-the-night directionless state, the hangover seemingly arriving even before sleep. Ingvartsen set out to record “what living in times of crisis does to our bodies” and the result is both adrenalised and bleak, if never as precisely delivered as Make It Count.

Ingvartsen’s dancers are seeking a release, a transformative state, like Haitzmann jumping rope. Or, in less extreme ways, like so many taking part in the open air classes around town at a festival that favours night owls with its 11pm show times and after-hours parties. Crossing the Danube late one evening, I spy a makeshift stage full of couples swaying right by the water. Here is a city that never sleeps – because it just keeps dancing.

-

ImPulsTanz: Vienna international dance festival runs until 10 August. Chris Wiegand’s accommodation was provided by the festival.

3 months ago

57

3 months ago

57