‘What a cock-up!” Those were the words that ended the first broadcast on the world’s tiniest TV station. Hours earlier, four young locals had been wrangled into being live presenters at their quiet village Sunday school. Despite dead air and awkward line delivery, it was the poor transmission quality that made the stars – Michelle Hornby (31), Jonathan Brown (27), James Warburton (25) and Deborah Cowking (21) – apologise and cut the inaugural broadcast. But Cowking, not realising they were still on air, slipped past the censors and summed up the evening’s vibe perfectly: chaotic, amateur and unrelentingly British.

This was The Television Village – a first-of-its-kind social experiment from 1990 that had the Lancashire village of Waddington “watch, make and become” television. For a short spell in the early 90s, the Ribble Valley was worth a fortune, as Granada Television shipped £3m worth of cutting-edge TV equipment to the rural hills of north-west England. Hidden cameras were set up in villagers’ living rooms to record viewing habits, day and night. Meanwhile, Channel 4 filmed the entire thing for a six-part documentary series. All of this was to monitor how people would react when the number of channels made the leap from four up to 30 – offering everything from sport, film and even porn, with villagers having access to terrestrial, cable and satellite channels, including from Europe and the US.

But one of the new channels caught the village’s attention more than any other: Waddington Village TV. Granada felt that local programming and local TV stations would be the future, so they gave villagers a station they had control over to see how popular it would prove. With dedicated presenters and sets put together with old settees and gaffer tape, the DIY station became an eclectic outlet, broadcasting self-written soap operas, horoscope readings and magic tricks. Think cheesy stock music and thick Lancashire accents. Yet without autocues, makeup or professional technicians, WVTV became a smash hit, gobbling up 95% of its available audience, technically making it the best-performing station in the world. When Coronation Street was knocked off its pedestal, Granada knew something was up.

“The villagers all loved it,” says Cowking from a seat in the Lower Buck Inn in Waddington, “because they’d see themselves, see their families, see the vicar.” According to Cowking, Granada hadn’t anticipated the channel’s success: “When they first started filming us and doing it, they actually said: ‘Don’t worry about it, it probably won’t even air.’”

None of the team of four had wanted to be presenters, but the village of about 400 had a small pool of willing participants. Brown had volunteered to help out with the cameras, but instead found himself in front of them.

Most of the ideas for WVTV programming came from this Waddington four. Students from then-Lancashire Polytechnic were tasked with producing the shows, which were recorded in front of a live audience. There was the vicar’s Thought for the Day, keep fit classes and a cooking programme by the butcher’s wife Barbara. “In a small community you run out of things you can do a feature on,” Cowking admits. “But when you think about it, Barbara probably came before Nigella Lawson.”

“We weren’t journalists,” Brown says. “We still had to live in the village when the TV people had gone.”

This lack of formal training came back to bite the presenters multiple times. Hornby remembers being chastised by a producer for ruining “continuity” after getting a perm; Terry Jones of Monty Python fame tried to eat the studio’s pet goldfish during an interview; and the whole production was put at risk when a Weetabix box that was being used as a prop to hold up scripts out of sight of the camera was accidentally broadcast, potentially breaching advertising rules. Numerous people involved with the station recall the broadcast being interrupted, only for it to turn out that a sheep had chewed through cable wires.

Waddington’s kids were also roped in, with three hours every Saturday dedicated to programmes made for and by young villagers. Gilly Czerwonka, a teacher at the time, helped gather a pool of children to write and star in the shows – often without any form of parental consent. She recalls one episode where the youngsters acted out a robbery on Waddington post office and high-tailed it in a car she had to drive.

Despite gaffes and a low budget, the presenters were a smash hit with the locals, and WVTV made news across the globe, with the 21-year-old Cowking even receiving fanmail. But the coverage wasn’t without its snobbery.

“There was a lot of condescension,” says Luise Fitzwalter, the editor of The Television Village, “these ‘hicks from up north’ – which was absolute nonsense.”

“Everyone adored it,” she continues. “People from far and wide were climbing on their roofs and turning their aerials to get the village channel instead of Coronation Street. Granada said to me: ‘What have you done?! Our flagship programme!’”

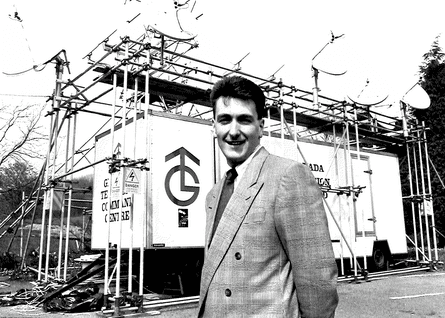

The production side of the experiment was a monumental task, with engineers, researchers, producers and camera operators living in Waddington for two months in the lead-up. Fitzwalter says they thought it would be “great, great fun and terribly naughty” to persuade the global manufacturers of the latest tech – from widescreen TVs to Sky – to send their prototypes to a remote village in Granadaland. Though the cabling had been hidden in the stream that runs through the village’s award-winning scenery, the imposing, aerial-adorned command centre in the car park of the Higher Buck pub caused Cowking’s mother to exclaim: “If nana came back to life now, she’d think the sputniks had landed!”

Naturally, the parish council wanted to keep an eye on things – as did the Independent Broadcasting Authority once they found out what was happening. “We had created a channel without asking anyone if we could,” Fitzwalter laughs. The village channel even made adverts for local firms, but allegedly had to return the money after the IBA caught wind.

Just before launch, legal tangles around copyright threatened to kill the entire project. Until, according to Fitzwalter, Granada company secretary Alastair Mutch said: “Oh stuff it, let them sue.”

Luckily for Granada, no complaints ever came in, nor did the porn channel spur outrage. “We agonised about it,” says Mark Gorton, the second director of the experiment. “We went round with forms, basically saying that if people were driven mad by smut that it wasn’t Granada’s fault.”

“At the last minute on the night of the launch we bottled it and left it out of the package. Only to be greeted by a delegation of village folk who arrived at the head end and demanded it be switched on.”

Gorton points out how The Television Village was a precursor to today’s deluge of social experiment programming: “We treated it as an investigation. It was pre-reality TV, so the way it was made was like an observational documentary. We put cameras in people’s homes and we’d film people watching television. Gogglebox cast them brilliantly, but we just let people be people. The rules of reality TV didn’t exist.” “We were the original Gogglebox!” Brown adds proudly. This televisual wild west is best encapsulated by Gorton’s memory of watching two hours of one villager wordlessly watching television before falling asleep to the 10 o’clock news.

Despite the impact of WVTV, none of the villagers got paid for their involvement – not even the four stars who did shifts every weekday. Hornby speaks of having to juggle her presenting responsibilities with two young children, and her brother Brown still feels let down after everything ended: “The TV people went, it all switched off, and that was it – gone.” Warburton, who now owns the Lower Buck pub, prefers not to discuss the project at all.

The major findings of the experiment were that viewers loved sport and film, much to the glee of Sky, who had provided these channels. But more surprisingly, it found people love programming made by the people around them. There was a buzzing sense that the hyper local was the future of entertainment.

Thirty-five years later, the experiment has been proven correct. But instead of charming local production studios, hyper local programming today is pumped out by accounts on YouTube, Facebook and TikTok. History has shown WVTV as one of the earliest examples of user-produced content, well before everyone had the ability to record and publish whatever they wanted.

“What has come to pass over the 35 years,” Gorton says, “is that anyone can present a television programme. We’ve learned anyone can be good – can be great – at it.”

The experiment had launched in March, and by late April the cable was fished from the Waddington stream and the cameras were packed away. Brown and Cowking had aspirations to enter television professionally, but life seemed to have other plans. Today, many of the young people of Waddington have no idea what took place in 1990, when for a few months cameras seemed to outnumber people – when the village was full of chatter about satellites, aerials and invisible waves from space. A number of those involved have since passed away. The only permanent reminder of the experiment is an easily missed wood-cased silver plaque by the war memorial that reads: WADDINGTON The Television Village.

1 month ago

36

1 month ago

36