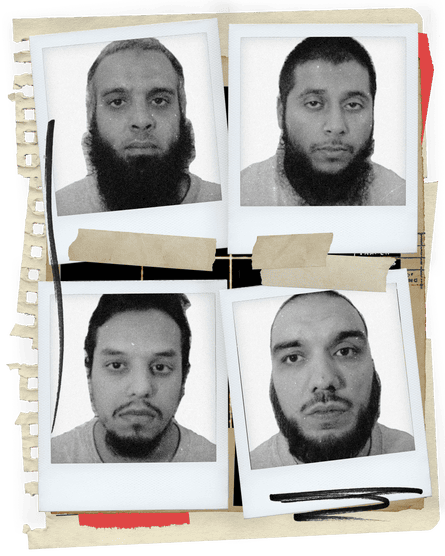

In August 2017, four men were jailed for life at the Old Bailey for plotting a terrorist attack. They were caught in an undercover police sting, and their defence lawyers insist their case continues to raise troubling and pressing questions ...

On Friday 26 August 2016, Naweed Ali drove to his first day of work at a delivery company in Birmingham. His next door neighbour and close friend Khobaib Hussain had already been working at Hero Couriers for a month. The name seemed appropriate. There was something heroic about the work they did. Ali and Hussain were hired to drive around the country reuniting airline passengers with lost property. The pay was great, too – £100 a shift, cash in hand. It seemed too good to be true.

So it proved. Hero Couriers was a front for Operation Pesage, an undercover police operation.

When Ali arrived at Hero Couriers in Birmingham at about 7.15am in his Seat Leon, he discovered there were double yellow lines and nowhere to park. His manager Vincent told him he’d park the car for him in the lock-up, as he’d been doing for Hussain. Ali happily handed over his car keys.

Vincent, like the other two men working at Hero Couriers, was an undercover cop using an alias. At 8.45am, MI5 officers arrived to insert an audio bugging device into the car. They found a drawstring JD Sports bag sticking out under the driver’s seat. It contained a “partially constructed” pipe bomb – a section of narrow pipe half full of explosive powder bolted to live shotgun cartridges. And there was more: an unfired 9mm bullet; a magazine attached to an air pistol with tape; and a meat cleaver with the word “kafir” (unbeliever) scratched across it.

A year later, in August 2017, four men, including Ali and Hussain, were jailed for life at the Old Bailey for plotting a terrorist attack. The judge, Mr Justice Globe, said he was satisfied it was only because of the work of undercover police and the security services that a terrorist attack “involving a considerable loss of life” had been stopped.

After the verdict, the renowned lawyer Gareth Peirce, who represented Ali and Hussain, did something she’d never done before. She issued a public statement questioning the jury. “We register our unqualified respect for the system we have of trial by jury in this country,” she said. “But jurors can on occasion get things wrong.”

Peirce is famous for successfully fighting miscarriage of justice cases, representing Gerry Conlon of the Guildford Four, and also the Birmingham Six, who had their terrorism convictions overturned in 1989 and 1991 respectively. She was appalled by the verdict in this case, saying it reminded her of the 1970s, when innocent Irish people were being framed for terrorism offences – only now it was Muslims. That’s when she started referring to the men as the Birmingham Four, a deliberate echo of the previous wrongful convictions.

The trip to Pakistan and the courier job

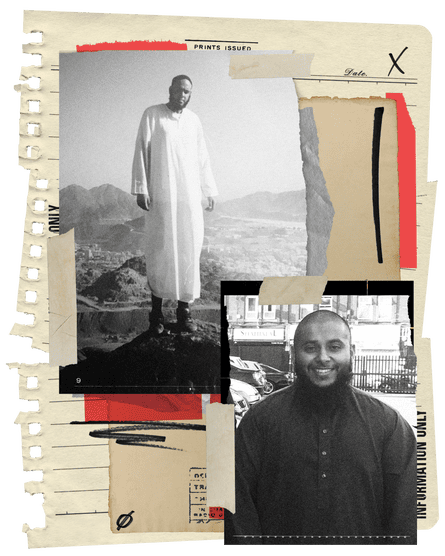

It all started six years earlier, in August 2011. That was when Hussain and Ali first got into trouble. After being radicalised by local Islamists in Birmingham, they decided to join a military training camp in Pakistan. Hussain was a 19-year-old law student; Ali a stuttering 23-year-old who had been on the special educational needs register at school. As soon as the boys arrived in Pakistan, they panicked. Their parents rang to ask where they were. They told them everything and said they wanted to come home. Their parents told them not to do anything stupid and arranged flights for them. Three days later, they were back in Birmingham. They seemed to have got away with it.

Three months later, the police raided their homes and they were arrested. Mariam, the oldest of Hussain’s four sisters, says it was the most terrifying day of her life. “It was horrifying. We were so young, and we’d not got a criminal record, but we were all treated like criminals. It took a massive toll on us.” Hussain and Ali pleaded guilty to preparing for terrorist acts and were sentenced to 40 months in prison. The judge, Mr Justice Henriques, acknowledged the pair, “took the decision not to proceed with terror training and … realised what a shocking mistake you had made”.

The two men were released in 2015. Mariam says Hussain was determined to rebuild his life, but it soon became clear what a struggle this would be. His conviction meant he couldn’t continue his law degree at the University of Wolverhampton. His bank account was closed. When prospective employers found out about his conviction, they wanted nothing to do with him. “You can’t live a normal civilian life,” Mariam says. “Every door was closing.”

So when Hero Couriers got in touch, he couldn’t believe his luck. Hussain had put his CV online, saying he was looking for work and had a clean driving licence. For the first month, everything appeared to go well. But his sister’s car, which he drove to work, had been bugged. After four weeks, the police team appeared to get impatient. They were convinced Hussain was up to no good, but he had given nothing away.

That is when Ali was invited to work for them, too. Remarkably, on his very first day the pipe bomb and weapons were discovered in his car. The two men were arrested and held in custody. Police believed they were in this together. After all, both men had travelled to the training camp in 2011 and been convicted.

On the same day, two more men were arrested in Stoke. Mohibur Rahman had met Ali and Hussain in prison. Rahman had also been convicted of a terror offence in 2012 after pleading guilty to the possession of an al-Qaida publication with terrorist content. The fourth man, Tahir Aziz, had only recently got to know Rahman. A large samurai-style sword was found by the side of the driver’s seat of his car. Police captured an image of the four men walking in a park five days before they were charged.

Operation Pesage was created on a hunch, that Khobaib Hussain and Naweed Ali were a threat to public safety, having already been convicted of a terror offence. The other two, Rahman and Aziz, were identified by the police later as co-conspirators. If the men were rightfully convicted, Operation Pesage may have saved many lives. If they were wrongfully convicted, there may well be police officers who still feel it saved lives because Hussain and Ali had travelled to a training camp in Pakistan. But there was no suggestion in 2011 that the two men ever wanted to attack a British target. They say their dream was to help overthrow the regime of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, because, as Hussain put it: “My view was, and is, that Assad has committed genocide by dropping chemical weapons on the population.”

The trial began in March 2017 and lasted four and a half months. The jury was told about Hussain, Ali and Rahman’s previous terror convictions. The undercover officer Vincent was the main prosecution witness, giving evidence over 15 days behind a screen, including 12 days of cross-examination. The jury was introduced to the concept of “mindset evidence” – evidence based on the defendants’ state of mind, mainly derived from what was found on their devices. They heard how Ali, Hussain and Rahman often communicated with a larger group of about 30 people through the encrypted Telegram app. The prosecution showed that they shared content about violence across the Muslim world and hatred towards the west, praising men who had laid down their lives for Allah on foreign battlefields. It argued that this reflected a terrorist mindset, but the men said they bore no hostility to the west.

The Three Musketeers and Telegram

On 11 August, 15 days before the JD Sports bag was found in Ali’s car, Hussain messaged him and said: “Make new group… me u n Mohib only.” The encrypted Telegram chat was called The Three Musketeers Group, represented by a cartoon of the characters from the 1993 Disney film. They spoke to each other about visions of heaven, how guilty they felt at having done so little while others made real sacrifices. Days before their arrest, Ali and Hussain made an overnight trip to Rahman’s home in Stoke. He messaged to tell them not to bring their phones, but to use pay-as-you-go handsets he had bought on eBay for the three of them. By now, the prosecution argued, the Musketeers were set on wreaking terrible damage.

Much of the mindset evidence hinged on phone messages sent the night before they were arrested. The men chatted by text about a National Geographic documentary called The Liquid Bomb Plot, about the surveillance operation that prevented a mass transatlantic terror attack in 2006. Rahman posted a link to the film; Ali’s browsing history showed he was searching “liquid bomb plot”. Ali posted to the group: “May Allah make it easy for us.” Rahman told his friends, “I feel so guilty. Look how weak I’ve become. I can’t even make a sacrifice as little as my PS4 [games console].” Hussain texted: “What are we doing, akhi [my brother]? Sitting here, working, and that’s it.” He added. “Nothing happening – we just talk. We gotta do something.” The prosecution argued that Tahir Aziz was brought into the plot right at the end by Rahman.

There was no talk of a plot. Rather than being men of action, they appeared to be men of inaction

But the defence argued that the prosecution had joined unconnected dots to create a fake narrative. They said there was no evidence that they would go on to do something. Or what that something could have been. There was no talk of a plot. No mention of bombs, guns or gunpowder. Rather than being men of action, they appeared to be men of inaction. In fact, many of the messages they sent each other suggested apathy and uselessness, and a comic self-awareness about it – they couldn’t even sacrifice their games consul for Allah, while others sacrificed their lives. They even joked about their inadequacy, comparing Ali with one of the useless characters from the satirical film Four Lions.

At the Old Bailey, the undercover police gave evidence behind screens. They described how the fake courier group was set up, how they bugged Hussain’s car, how MI5 arrived just in time to find the deadly bag of explosives and weapons in Ali’s car.

The undercover officers insisted they had not been in touch with each other throughout the trial. But the prosecution was forced to disclose an astonishing trail of communication. The police initially insisted phone messages had been deleted. After the defence said they had access to experts who could recover them, the prosecution produced more than 1,000 “deleted” texts between Vincent, his fellow undercover officers Andy and Haji and their unit, going back to Hussain’s recruitment a month before the raid and continuing through the trial. Vincent texted his boss during the lunch break on the first day he was being cross-examined, but he insisted it was about a personal matter and not the evidence. Vincent and Andy also met at a service station and layby during the trial. The defence said that officers from the unit perjured themselves and fabricated evidence in court, alleging that Vincent had planted the incriminating evidence in Ali’s car. In his summing up, Justice Globe said: “Vincent said that he had an unblemished career in law enforcement. He said he had never been investigated, disciplined or prosecuted for any criminal offence in his career. He took exception to the allegation that he had committed the criminal offences of planting evidence, concocting evidence and committing perjury.”

The police texts and DNA evidence

The officers were old-timers working for the Counter Terrorism Unit of West Midlands Police, whose Serious Crime Squad had been disbanded in 1989 after a series of set-ups, cover-ups and forced confessions. The exchanges are brazen. Before giving evidence, Vincent texted his boss to say: “I’m even more determined to put in an Oscar performance when I get in that box.” In another message, he writes: “We are getting older … but not too old to twirl them and put them away for a long time,” signing off with a winking emoji.

Vincent texts his fellow undercover officer Andy, who is about to retire, and says he hopes his leaving card gives him a laugh. Andy replies: “Not as much as reading your statement earlier!!! Joke joke joke …” In court, Stephen Kamlish KC, defending Ali, read out Vincent’s “farewell” text to Andy, in which he mentioned how much he was going to miss him as a colleague: “So you wanker … U leave me with a load of fucking wet wiped nob heads who don’t know how to put a job together wipe arses or cover tracks … Wanker … Miss you.”

From the recovered messages, it appears Vincent has psychic powers. A month before the MI5 findings, he predicts something pertinent will be found in a car. Then, just before the MI5 officers arrive, he tells his boss “they will look and photograph anything”, even though there is no reason to anticipate finding anything. At 8.19am that day, he tells Haji, who is away from the depot, that there “has been a development” and he shouldn’t return immediately – but the MI5 officers hadn’t even arrived by then, never mind made their discovery.

A major difficulty for the prosecution case appeared to be connecting the bag to the other three defendants. The police had suggested it was the same JD Sports bag Hussain had regularly taken to work, but it turned out his bag was black and white and this one was coloured. The prosecution had also hoped to show the jury evidence that Hussain’s DNA was on the weaponry in the bag. But this evidence was initially ruled out. Three months into the trial, a new ruling allowed the evidence to be put forward, and now the jury saw why it was so controversial.

Among the messages that had been deleted by the police officers was an elliptical one from Vincent sent a month after the JD Sports bag had been found, saying: “It’s a sticky tape story – you were right.” It appeared to be a reference to sticky tape that was found binding the magazine to the gun, but its meaning was opaque. However, when the prosecution finally presented their DNA evidence, another reading became clear. Hussain’s DNA was found on the adhesive side of the sticky tape. But so, surprisingly, was that of his sister, Aisha, who owned the car he drove to work. In fact, most of the DNA evidence belonged to Aisha, who was never charged. The defence said there was a simple reason for this – that Hussain had been framed. It suggested that the DNA had been obtained by pressing the adhesive side of the tape to the steering wheel of the car owned by Aisha and driven by Hussain or to tissues (later found in the incriminating bag) from the glove compartment.

The defence waited for the case to be thrown out. But it wasn’t.

What nobody could have anticipated was the febrile atmosphere in the country and in court. During the 2017 trial, four terrorist attacks occurred in England: five people were killed on Westminster Bridge on 22 March, the day the trial started; 22 people were killed and more than 200 injured in the Manchester Arena bombing on 22 May; eight people were killed on London Bridge on 3 June; and one person was killed and 12 others injured in Finsbury Park on 19 June. All but the final crime were committed by Muslims.

The judge warned the jury to ignore what was happening in the outside world, but this was easier said than done. One day a jury member turned up late. She told the judge she had seen a man reading the Qur’an on her train into court, and feared he was a terrorist, so she got off and waited for the next train.

At times, the trial resembled a farce. In July, a jury member was discharged after asking the court usher on more than one occasion to find out whether one of the police officers (who wasn’t undercover) was single, after another juror told her she found him attractive. The juror who had made it clear she was interested in the officer was not discharged, even though the defence argued this undermined the impartiality of the jury and that the entire jury should be discharged. Justice Globe said: “I have had to ask myself if it is so important that I should not allow you as a group to continue considering this case.” He did allow them to continue.

Everything about the case was mired in controversy. Barristers for the defence, Kamlish and Rajiv Menon KC, defending Hussain, alleged that Justice Globe’s summing up of Vincent’s evidence was unfair. Menon told the judge: “In our submission, this deadly combination of bias, distortion and omission in this case crosses the line into what is impermissible comment on the evidence.” Justice Globe responded: “I reject all defence propositions. I dismiss the applications to discharge the jury or to alter the summing up in relation to Vincent’s evidence.”

On 2 August 2017, the jury returned a guilty verdict, and all four men were given life sentences – Ali, Hussain and Rahman a minimum of 20 years in prison, Aziz a minimum of 15 years. Justice Globe said the men were gripped by a “long-standing, radical, violent ideology”. In his sentencing remarks, he said: “But for the intervention of the counter-terrorism unit of West Midlands police and the security services,” he believed there would have been, “terrorist acts in this country using at the very least the explosives and/or one or more bladed weapons.”

The parallels with the Birmingham Six

At the top of a terraced building in Camden town is the office of Gareth Peirce. On the shelves are numerous files documenting many of the great miscarriages of justice and state scandals of the past half century – the Guildford Four and Birmingham Six; Orgreave miners beaten by south Yorkshire police; Jean Charles de Menezes killed by the Metropolitan police; Moazzam Begg, who was detained in Guantánamo Bay.

She looks remarkably unchanged from how she appeared almost 36 years ago, when the Guildford Four were acquitted (Peirce was played by Emma Thompson in the 1993 film, In the Name of the Father). Same sea-blue eyes, bobbed hair, long black dress and boots. And the same grasp of detail.

For Peirce, this case is personal. In many of her other battles, she became involved post-conviction to clear up the mess. With the Birmingham Four, she was there from the start. “This was our trial. It was on our watch. It’s our continuing responsibility, and they shouldn’t have been convicted.”

Peirce says she realised she was dealing with a familiar pattern of behaviour when she discovered the officers had been using notebooks and had handwritten their notes. One text reveals that a week after the arrests, Vincent’s boss texted him to say: “We have agreed … that you will write your pocketbook for Pesage, not type, hope that helps.” This was years after West Midlands police had computerised their notes. Kamlish pointed out in court that Vincent and Andy were the only two undercover officers in the West Midlands Counter Terrorism Unit to have used them since January 2015.

She’d seen this before, when the same police force investigated the Birmingham Six in the 1970s. “I said: ‘I know this!’” She raps her fingers on the desk. “I’m saying to our team: ‘Look at this, look at this, we’ve seen it before.’ The West Midlands Serious Crime Squad used notebooks to record alleged contemporaneous interviews and what led to their downfall was the elementary concept of, if you write something and rip out that page, there’s an indent of what you originally wrote.” She rips out an imaginary page. “That’s what ended the Birmingham Six and Guildford Four in the end.” The final page of Vincent’s notebook was missing. “He was told, ‘It’s OK to write up your notebook now a week later’, but his evidence is that his notebook had been created day by day as a log. Yet it was all in the same ink, continuous. It was complete nonsense. And then he got the date wrong. So he had one entry the day before it actually happened!’’

Mariam listens as Peirce talks. I ask Mariam why Hussain and Ali went out to Pakistan in the first place. “There was a lot of unrest in the Muslim community about Syria,” she says, “similar to what we’ve just experienced with Palestine. If you’re practising and you’re from the religion of Islam, it doesn’t matter if you’re not blood related, you’re cast as one nation, and you feel that empathy for one another. But when that trial concluded, the judge said these were young men who made the wrong decision and were influenced by older people.”

She says the trouble is that so many people seem to believe that, even if the police operation was a set-up, it’s acceptable, because her brother and Ali had gone out to Pakistan in the first place. “Everyone makes mistakes, everyone’s human. They were really young at the time. It feels like double standards – Muslims aren’t given a second chance.”

Did they get to the training camp? “They got to the first stop and then one of them rang home, and they fell apart,” Peirce says. “The grandfather of one of them had to bring them back because they were so frightened and had got themselves in such a mess.”

Peirce seems fond of the men she’s representing, but she doesn’t mince her words about them. “There was a pecking order in the Pakistan trial because there were older men who were trying to get involved in something more serious [three of the men were given life sentences for plotting suicide-bomb attacks] and then some were trying to siphon off money that had been raised for good causes, and then right at the bottom you had these chumps!”

I ask Mariam about the evidence that the four men were planning a terrorist attack in 2016. She insists it’s nonsense. Take the Telegram app. “I’ve got Telegram. It’s a social app like WhatsApp. And in terms of content that’s shared in the joint app, it’s content that’s shared quite widely.” What she means is that you’d find many orthodox Muslim men saying similar things about feeling bad that they’re not supporting fellow Muslims abroad.

At the trial, lyrics were quoted from nasheeds (songs focusing on Islamic values) that the men were listening to in a similar way that drill music has been used in the prosecution of young black men in Britain. “Khobaib and Naweed didn’t even speak Arabic,” Mariam says. “They didn’t understand what they were listening to.”

The unlikely couple

Naweed Ali declined to give evidence, citing his stutter and lack of confidence. This proved disastrous. After all, the case began with him. The bag was found in his car. It meant he never challenged the charges against him, first-hand. Much of the mindset evidence could be accounted for relatively simply, but the “liquid bomb trial” references proved difficult, particularly as Ali didn’t take to the stand to say why he had been searching for it. Later in the trial, Hussain explained that on the night before their arrest the three men had been chatting about how they had watched The Liquid Bomb Plot while they were in prison. He said Rahman wanted to watch the film again because he had met some of the plotters in prison. Rahman’s reference to feeling guilty, Hussain said, was because he felt he should be financially helping prisoners he had been jailed with and their families more than he was. When Rahman gave evidence, he provided a similar account.

As for saying, “We’ve got to do something … just nothing really happening”, Hussain insisted that was nothing to do with any plot, it was about the general rut the three of them were in – their failure to help other prisoners and their families financially as they had pledged to; their lack of marriage prospects; their failure to find fulfilling jobs. Although he was pleased to be doing shifts for Hero Couriers, it was hardly the law career he’d anticipated. “I didn’t feel I was progressing … I wasn’t able to move on like others in my family,” he told the court.

Mariam says Hussain and Ali have been monstered by the media, and the reality couldn’t be more different. She describes them as an unlikely but lovable odd couple – Hussain, smart and academic; Ali, older and so unsure of himself. “I think what connected them is they’re very simple souls.” She talks about the innocence of Ali – the way he dressed, she says, is almost a metaphor. “Naweed wears Islamic dress – a thawb. You can’t hide anything in a thawb. Everything would just stick out. For me, that’s a reflection of his personality. He is so pure.” But that’s not how the jury saw it.

Lawyer Matt Foot says he will never forget the day he was called out to represent Hussain and Ali after they were arrested. Not only did Hussain and Ali know nothing about the offences they were alleged to have committed, he says, nor did the police officers interviewing them. “It’s the scariest situation I’ve ever been in. It became apparent that the police who were interviewing did not know the provenance of the key exhibits that were being put to Naweed and Khobaib, which formed the basis of the whole allegation.”

Back then, Foot, co-director of miscarriage of justice charity Appeal, was working for the law firm Birnberg Peirce. For two weeks, Hussain and Ali were interrogated by the police. Foot had previously represented them when they were charged after travelling to Pakistan. This time though, he says, they didn’t have a clue why they had been arrested. “I saw their reaction independently of each other and that helped to confirm it. It was like something out of The Trial. Completely Kafkaesque.” He remembers them being shown a photo of the meat cleaver with the word “kafir” scratched into it. “I asked the officers who found this and when, and there was no answer.”

At that point neither he nor Hussain and Ali had been told Hero Couriers was a fake company. “I went to check out the place, and there was nothing there,” Foot says. “There’s no company. I’m asking people who work in the street have they seen anything and none of them want to get involved. It’s like: what is going on here?”

The samurai sword

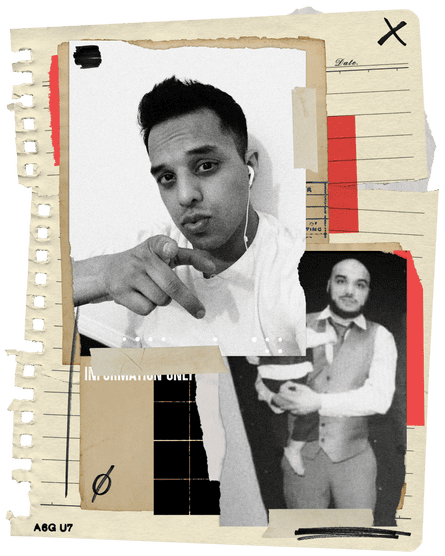

On Friday 26 August 2016, Tahir Aziz had just finished his shift at Primark as a retail assistant and collected his children from school. Aziz’s life was largely divided between work, his kids and the mosque. But the mosque was relatively new to his life. He had spent much of his life as a secular Muslim, and had two children he adored with his non-Muslim wife. It was only since they had separated that he had found comfort in religion.

The children split their time between their mother and Aziz, who lived with his parents. He tried to work around them. So he’d end his shift at Primark in time to pick them up from school, then in the evening he worked as a delivery driver for a local takeaway.

On this particular evening, he stopped off at the petrol station to fuel up. As he stepped out on to the forecourt, he was pinned against the wall by police and arrested under the Terrorism Act. “He didn’t know what was happening,” his sister Nazreen tells me. “He said: ‘I haven’t done anything.’ We didn’t see him until he was in court months later. He was taken straight to Belmarsh. It was so shocking.”

We are talking by video link. Nazreen, who lives in Stoke, starts crying. She still hasn’t recovered from the shock. Nor has her family. “Dad was a kidney patient. His kidneys were functioning at about 40% and when my brother was arrested they dropped significantly. He got to a stage where 5% of his kidneys were working.” She tries to speak, but no words come out. Her father died in July 2018. “It was too much for my dad. Tahir was the son my dad relied on. He used to take him to hospital, look after him, and give him money towards the running of the house.”

Aziz was the second eldest of seven children, with four sisters and two brothers. Nazreen, the oldest sibling, a former phlebotomy supervisor who has retrained as a lawyer, says all three boys struggled at school in an Islamophobic environment. They were provoked, got into trouble, and one by one they were expelled before their GCSEs. After Aziz was kicked out of school, Nazreen says he started hanging out with two men who were a bad influence. All three were sentenced to five years in prison for selling drugs. He was only 19 or 20 when he was convicted. When he was released, he settled down to life as a hard-working father and didn’t get in trouble again until that moment on the forecourt in 2016.

Aziz, who was 38 when convicted, is another puzzle in the story of the Birmingham Four. He had only got to know Rahman in the months before his arrest and had only just met Hussain and Ali. Even the prosecution struggled to explain his involvement. He was clearly not one of the “Three Musketeers”. Unlike the other three, he was not under surveillance. The prosecution argued that although he was a latecomer, he was a co-conspirator and that the sword found in his car pointed to his guilt. Aziz said it was an ornamental Japanese sword he had bought from a sports shop as a deterrent to would-be attackers he encountered while delivering takeaways.

The prosecution pointed out Aziz had downloaded extremist material, including the al-Qaida English language magazine Inspire, which featured an article on how to make a bomb. Aziz said he had deleted it as soon as he had seen what it contained. Kamlish told the jury: “You may despise the things they were looking at online, but it does not mean they were plotting to kill.”

Although the jury was ordered to ignore the political climate, Nazreen believes it was impossible. Her brother and the other defendants, “were surrounded by these incidents and they were facing a terrorist trial. Even though the judge said not to take any of the matters happening outside into consideration, you can’t stop a human mind from believing that. It’s human nature to think: if we release these men, maybe they will attack.”

When she saw her brother in court, she couldn’t believe how different he looked. “He had always shaved his head and face or had a short beard. Now his hair and beard were long. They made him look like a terrorist by not allowing him to access a barber to have his beard or hair cut.” Had he wanted to cut his hair? “Yes, he did want to, and he wasn’t allowed,” she claims. “They wanted to show the jury, this is a person we have alleged is a terrorist and look at him.”

In court, Hussain described Rahman as “paranoid”. Perhaps it’s not surprising he was paranoid. Rahman told the court that, since 2015, two MI5 officers called “Rob” and “Greg” had made a number of attempts to recruit him as an informant. Rahman said Rob told him he was interested in Ali and Hussain and handed him £200 in cash as an inducement to work for them. (Ali had also been approached, separately, without success.) Rahman told the court that he feared for his life from MI5, and this was why he had sent Ali and Hussain new phones and told them not to use their regular phones in each other’s company.

The MI5 officers and the Court of Appeal

People who claim to have been unfairly convicted are granted an automatic right to apply for permission to appeal, and usually have to do so within 28 days of their conviction. In November 2018, the Birmingham Four’s appeal (founded on the judge’s refusal to discharge the jury or lift the anonymity order on the undercover officers, and his summing up of Vincent’s evidence) was rejected by the Court of Appeal.

In its judgment, Lord Justice Holroyde said: “We have considered whether anything put before us casts doubt on the safety of the convictions. We are satisfied that there is nothing that does so. The jury by their verdicts plainly rejected that the evidence had been planted. Having done so there was ample circumstantial evidence against each of the accused to support the convictions.” Now the Birmingham Four had to look to the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) if they wanted to challenge their guilty verdict.

The CCRC was formed in 1997 after a series of high-profile miscarriages of justice in the 1970s and 1980s, including the Guildford Four and the Birmingham Six. It was given new statutory powers to investigate alleged wrongful convictions and refer them back to the Court of Appeal when there were strong grounds.

Miscarriages of justice had previously been dealt with by a Home Office department known as C3. Peirce was a fan of the CCRC in its early days. “At the beginning, the commissioners who were first appointed were strong, confident individuals who’d had successful careers in another field. There was an energy there, and the original commissioners had a motivation to get cases referred back.”

That’s long gone now, she says. Today, the commission is underfunded, conservative, rarely uses its investigative powers and is unbelievably slow. Critics say that, rather than providing a gateway to justice, the CCRC acts as a gatekeeper for the Court of Appeal.

In 2023, Andrew Malkinson had his conviction for rape overturned 14 years after first submitting grounds to appeal to the CCRC. Last week, Peter Sullivan had his conviction for the murder of 21-year-old Diane Sindall overturned after spending 38 years in prison – thought to be the longest in British history that a person has been imprisoned before being cleared. The sentence was quashed after Sullivan applied to the CCRC again in 2021 and new forensics tests revealed that his DNA was not on samples preserved at the time. Sullivan first applied to the CCRC in 2008, asking the commission to look at DNA evidence that could exonerate him. Back then, testing was cruder, the CCRC was told by forensic scientists that they were unlikely to be able to recover useful DNA, and his application was rejected. The same testing technique led to his conviction being overturned 17 years later. Critics say if the CCRC had been more assertive or proactive, Sullivan would have been cleared years ago. On Friday, a committee of MPs published a damning report on the CCRC calling on its chief executive, Karen Kneller, to resign. In January, its chair Helen Pitcher resigned after successive justice secretaries indicated that they had lost confidence in her.

In the case of the Birmingham Four, Gareth Peirce believes they are hampered by all the evidence of police misconduct that came out at their trial. If it had emerged after the trial, she would have an easier job in convincing the CCRC to refer the case back to the Court of Appeal because the CCRC relies so heavily on “new” evidence in its considerations. “Every single thing that happened would have led to the case being reopened and the conviction quashed,” she says, “but because it all came out in a trial, the CCRC can say the jury heard all this and they convicted.”

The commission can demand to see evidence that was not disclosed to the defence. Peirce is convinced this would provide even more proof of an unsafe conviction. “They have the power to find internal evidence of discussions and decisions within police departments, but all they’ve done so far is send preservation orders to different bodies to preserve their records.”

At the end of the prosecution’s evidence, Peirce asked the judge to strip the undercover officers of their anonymity on the basis they had perjured themselves, most notably in saying they had not been in touch with each other throughout the court case. Justice Globe refused, rejecting the allegation of perjury. The police being undercover is a huge obstacle to justice, says Peirce. For example, if the defence had known Vincent’s real identity, it could have checked his spending history to see whether he had bought any of the items found in the bag, and tested his DNA and fingerprints to see if they matched that found on the tape. (The defence asked the prosecution to make both of these checks, but it refused.) In previous cases, Peirce has been able to investigate the history of officers she has suspected of corruption. Here, she is working in a vacuum.

It’s more than a year since she submitted grounds for appeal to the CCRC on behalf of Ali and Hussain. “It’s like a thriller that explains everything – the dynamics of the trial, the jury’s reactions, the impact of the terror attacks. It’s got everything they need to know.” The problem is, Peirce says, the CCRC is ossified and takes years to reach a decision. “So my next task is: ‘I’m going to point you to what you can do – forget all the rest, I’ll just point you to X, Y, Z.’” She’s talking to me, but addressing the CCRC. “We’ve baked your cake. All you need is a crumb and you’ll find more than a crumb here.”

Peirce and Mariam make a good team. “We know the CCRC have higher powers,” says Mariam. “They don’t need to be too fixated on new evidence. It’s just that this body chooses not to use those powers.’”

“So the case has been presented in both ways,” Peirce continues. “We’ve said there’s enough here for you to just send it back. However, if you think there needs to be more, this is the more that didn’t come out, or this is the route to more.” When I ask what the more is, she becomes coy. “A couple of things I can’t tell you because they’re personal and they require consent, which we don’t have.”

There’s another problem, Peirce says. Lack of popular support. Again, it’s familiar to her. She experienced it when she took on Irish cases decades ago. Now it’s the same with Muslims. And what further complicates matters is the previous convictions of the two men she’s representing. “We’re in a very tricky situation because the subject is terrorism. And if you’re a convicted terrorist there isn’t a great lot of sympathy there.” Her frustration is visceral. As far as she is concerned, she’s dealing with a blatant miscarriage of justice that is destroying the lives of four men and their families.

I talk to Peirce soon after the death of Paddy Hill, a member of the Birmingham Six. She says it’s a reminder that history does repeat itself. “There are significant similarities between the Birmingham Six and Birmingham Four. The defendants were members of suspect communities, and evidence was fabricated with utter arrogance and self-justification by the police.” She refers to it as “noble cause corruption” – the belief that a group of people are dangerous and need to be taken out, with the ends justifying the means. “These undercover police are clearly corrupt and dishonest. Having defined themselves as being there for a purpose – to get suspects out of the way permanently – they have succeeded in doing so for decades.”

Mariam exhales loudly, and says she is praying the CCRC does the right thing – and quickly. “Every second wasted is so precious,” she says.

When asked to comment, West Midlands Police told the Guardian: “In 2018, a full Court of Appeal examined the safety of these convictions in great detail and upheld the findings of the jury.”

The Guardian asked the CCRC if it had ordered West Midlands Police and MI5 to hand over relevant documents that were not disclosed at the trial and whether there is a mechanism to speed up the review process. “I can confirm we have received applications on behalf of Mr Hussain, Mr Ali and Mr Aziz, and reviews are underway. It would be inappropriate to comment further while the reviews are ongoing,” a CCRC spokesperson said.

The impact on the families

In Sparkhill, Birmingham, Hussain’s father Shab is watching the snooker, cheering on Ronnie O’Sullivan. He’s just finished his shift as a cab driver. In the kitchen, Hussain’s mother Nusrat is cooking up lamb and loki, cauliflower and potato, pakoras, bhajis and chapatis. Mariam and her husband Faisal join us. Then Ali’s brother Ghaf and his mother pop round from next door. Neither family can disguise their devastation.

Around the dinner table they discuss all sorts – the mindset evidence, miscarriages of justice in general, Liverpool’s premier league title and who is the greatest snooker player ever.

But inevitably it returns to the case of the four men, and in particular their two boys. Ali’s elderly mother Parveen, who doesn’t speak English, clasps her hands in prayer. Ghaf translates. “She’s saying: ‘Can you help us?’ We’ve had so much stress. My dad passed away while Naweed’s been in prison and Mum says he didn’t get a chance to see his father, and she’s worried he won’t get a chance to see her.”

Nine years on, they still can’t get their heads around what happened. Ghaf boils it down. “Do they think Naweed is such an idiot that he’s going to go to work with a bomb in his car, and give them his keys?”

“Who the hell would do that ?” Shab says. “That’s the thing that gets me. Think about it. First shift!”

Hussain phones while we’re eating. The family hangs on his every word. He tells them what he’s been up to – doing his shift in the workshop, assembling headphones for Virgin Atlantic; gym early evening; bang-up at 6.30pm. He talks about what he would like the world to know about his case. “I just want people to know that miscarriage of justices do happen and people can get wrongly convicted and lost in the system. People know what happened in my trial, but the narrative always gets spun in a way, depending on the verdict. So if you get found guilty they’ll paint you into a monster.”

One reason he has found himself lost in the system is that the Ministry of Justice has made it so difficult for him to campaign against his conviction. The governor of the category A prison he is in rejected my request for a visit and the prison returned the letters I sent him.

After the cache of deleted police messages resurfaced, Hussain says he was sure the case would be dropped. “If Vincent, the key witness for the police, is in contempt of court and we’ve shown that their evidence is fabricated, surely the case has to be dropped. Stephen Kamlish burst into the room and said: ‘That’s it lads, we’re going home.’ He was so excited. But then it dawned on me that I was looking at getting convicted because of the climate.”

As Hussain talks to his family, it becomes obvious how aware he is of life passing him by. He says it’s his family and faith that are keeping him strong. “I know the truth always comes out in the end, and that keeps me going.” It’s not simply about recognising the innocence of the Birmingham Four, he adds, it’s equally important to address the behaviour of the police. “What about the guys who put us in jail? Unless there are proper repercussions for their actions, this kind of behaviour is going to carry on.”

After he says his farewells, everybody looks at each other, deflated.

“Don’t get me wrong, there are people with these ideologies,” Shab says. “If Khobaib had done something, I would say, yes, let him rot in there. But what boils my blood is all the evidence is there. They were monitoring him for months and didn’t find anything. At the end of the day, think about it, they’ve lost their life. Look at the family – what we have to suffer through. Over what?”

3 months ago

69

3 months ago

69