‘It’s always good to make yourself feel small,” says Stu Mackenzie. We’re sitting behind the stage of the Ancient theatre in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, after the second night of his band King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard’s three shows there. The marble-hewn amphitheatre was built between 98-117AD. We’re flanked by columns bearing ancient Greek inscriptions from back when this place was called Philippopolis; the precipitous drop behind us reveals the east side of Europe’s longest continually inhabited city, the glowing cross of the Cathedral of St Louis and the shadow of the hills in the distance.

In front of the stage where the Australian experimental rock band have just spent two hours wilding out is an arena where man and beast used to do battle in front of a far more bloodthirsty crowd than the one that just drank the venue dry of beer. It’s hard not to feel like a speck here, awesomely adrift in all of human history.

-

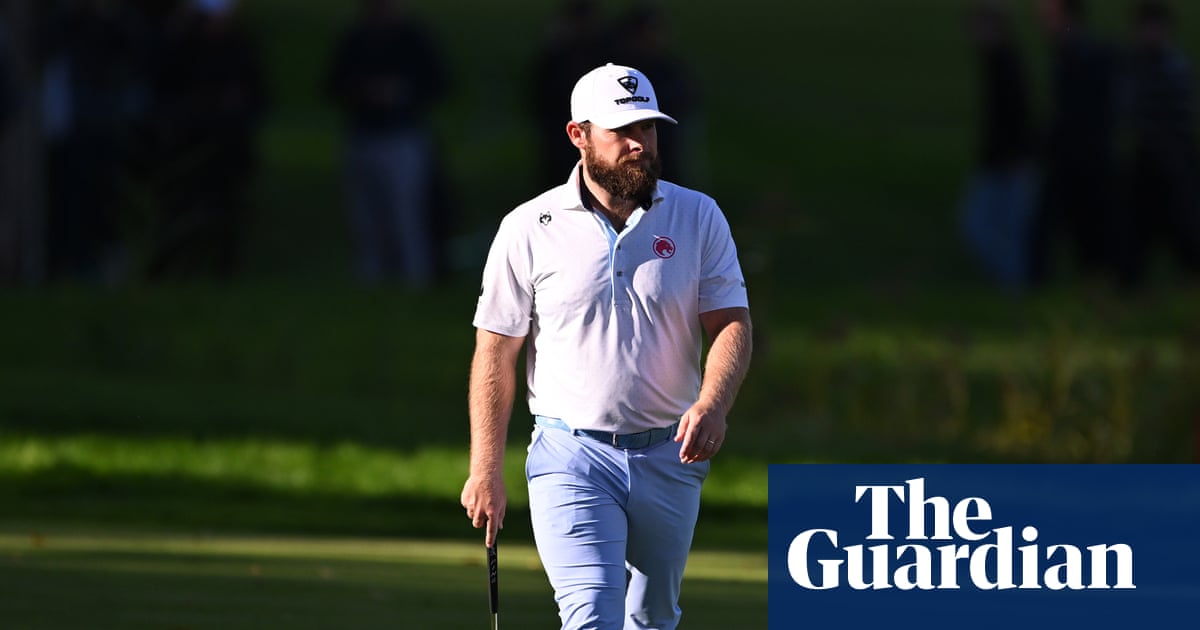

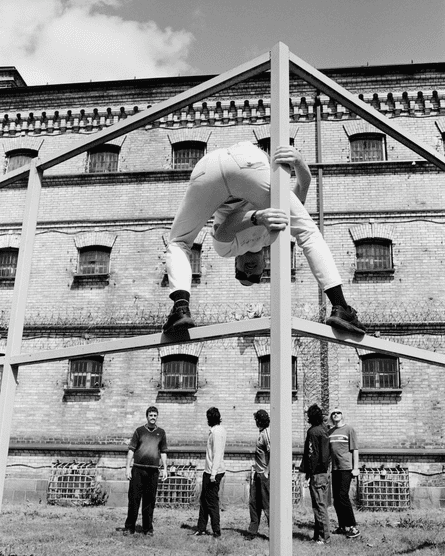

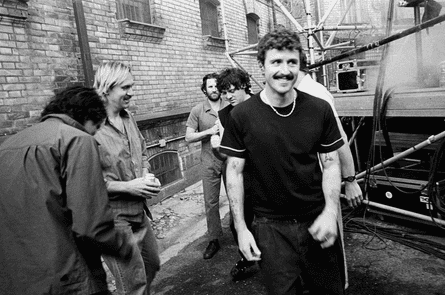

The band at Lukiškiu prison, Vilnius, Lithuania

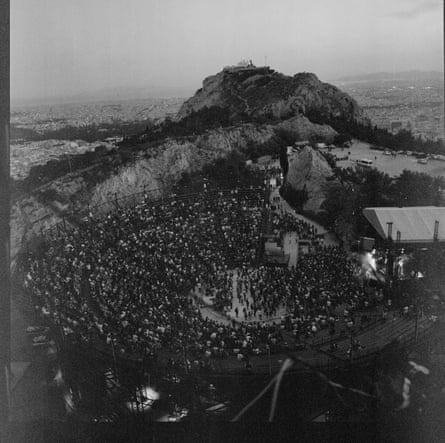

Plovdiv marks the end of Gizz’s European residency tour, which has seen the band post up in five different cities for three-night runs in historic or otherwise curious venues: the panopticon Lukiškės prison in Vilnius, which closed in 2019 and is now a venue; Lycabettus hill theatre in Athens. After similarly successful residencies at natural amphitheatre-type venues in the US, the band wanted to make sure their European fans didn’t get left out.

“We’re like tourists on this trip as well,” says Mackenzie, still in his sweat-dappled baby pink stage boilersuit. “The contrast between a regular bus tour, where we’re in a different city every night, is pretty stark. Usually you wake up after a long drive, you actually can’t remember where you are and it’s about orienting yourself – finding a coffee or a green space and just surviving. But on a tour like this, you actually have a moment to soak it up and breathe, which is rare. We’re having such a ball – spending time cruising around, eating, seeing the cities, just hanging out with each other – the good stuff.”

-

Boarding from Lisbon to Barcelona

-

Ambrose Kenny Smith on a day off in Hydra, Greece (left), and in Lisbon, Portugal

If anyone knows the price of hard-touring, it’s Gizz, who started as a party band in Melbourne in 2010 – hence the un-serious name, which stuck – and have gigged their way to becoming their generation’s Grateful Dead or Phish, bolstering their psych-rock with metal, krautrock, microtonal experiments and more. They’ve headlined Green Man and End of the Road, and this month saw the release of their 27th album, Phantom Island, where country choogle meets Philly-inspired soul thanks to their first foray into orchestral arrangements. It’s a beautiful if worried record, its lyrical protagonists often observing the world from the cockpit of a plane and wondering what the purpose of it all is.

-

Performing at Lycabettus theatre, Athens, Greece

The existential vibe feels right at home in these perspective-realigning venues, built on thousands of years of human existence. “A lot of the lyrics we’ve written together have stemmed from spending a lot of time away from home, from family, from kids,” says Mackenzie, who welcomed his third baby just before tour started, “and trying to figure out how we make sense of all of that, and the world. It has been an existential few records,” he agrees.

-

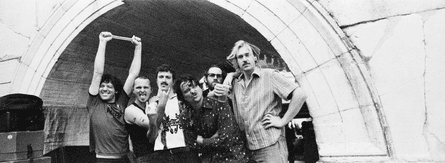

From left: Mickey Cavs, Stu Mackenzie, Joey Walker, Ambrose Kenny Smith, Lucas Harwood and Cook Craig backstage at the Ancient theatre, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Gizz run a staunchly DIY enterprise. They self-release their albums, which they still record in the same small studio in Melbourne. They’ve never worked with a producer. Their friend Jason Galea does all their artwork and Maclay Heriot takes their photos. They release free bootlegs of every live show – the Barcelona residency is already up on Spotify by the time they hit Plovdiv – and broadcast a high-quality livestream of each night on YouTube that they’ve taken painstaking care to perfect.

To outsiders, they’re perhaps best known for their prolificacy – in 2017 alone, they released five albums. Their output can be seen as intimidating, or perceived as some sort of novelty factor. But for Mackenzie, it seems more about the sense that every creative whim is worth honouring, and every bit of life really is worth figuring out creatively, indicative of a tendency towards archivism.

-

A member of the Weirdo Swarm at Coliseu dos Recreios, Lisbon

“You’ve nailed a big part of the motivation for it,” he says. “We as a group have a big appetite for risk. We’ve been good at just being in it together, and if this fails or people don’t like it, it’s fine. We’re all here together because we actually are all best friends, we’re really grateful to be here and I don’t think anyone wants to do anything else.”

The ambition isn’t to play the Royal Albert Hall, as they are this November; that’s just a nicely crazy surprise. “It does keep the motors greased and it keeps us on the horse,” says Mackenzie. “But it’s definitely not the goal. We’ve been pretty careful to honour that. As things become more seductive, we’ve tried to keep it feeling very small. There might be a few more people around, but I think we’ve been very protective of our little, tiny, miniature universe.”

But in another sense, Gizz is a beautifully open-source universe. They give fans – the Weirdo Swarm – their blessing to make bootleg merch and even bootleg records of their live recordings (they only ask that they send them a “fair” amount of pressings in exchange). Where much pop fandom constitutes little more than idol worship, the Swarm are a generative and self-sustaining community: on their fansite, they’ve put together a detailed guide to each city on the EU tour, including information about attitudes to LGBTQ+ people and drugs (both very censorious in Bulgaria). “I do feel really proud of that,” says Mackenzie.

-

From left: Stu Mackenzie and Joey Walker playing ‘Nathan’ at Lukiškiu prison

In Plovdiv, a group of local fans thrilled that Gizz have finally come to their country have organised daytime meet-ups at a bar before the first and last shows, where stickers and friendship bracelets are traded and bespoke posters are sold, as well as nightly afterparty gigs at a local bar. Once again, not a drop of beer remains at any event.

The atmosphere is radiantly sincere and celebratory. We meet fans from Denver who are almost always on acid; a kid from Belgrade who posts in the rapidly renewing Gizz sub-Reddit that he loves Plovdiv so much he wants to move there, and includes the details of his outfit so that anyone can come up and say hi, which we do and get a huge hug. We hear about the flight from the last date in Athens to the Bulgarian capital Sofia, which was filled with about 80 Gizz heads and the band themselves.

-

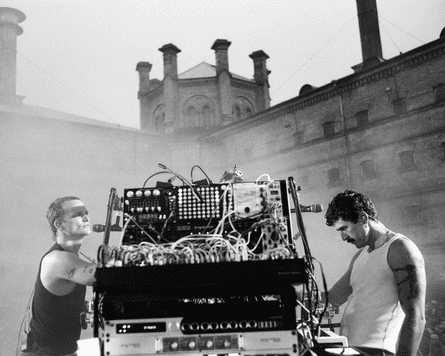

A closeup of Nathan

Tara from San Diego has seen the band umpteen times and used to be a Phish fan; the difference in the oft-compared “jam bands”, she says, is that Phish wig out into abstraction – catnip for casual listeners off their nut on drugs – while Gizz splice together intricate medleys of their songs, which rewards close focus from fans literate in their vast catalogue. One group of fans have made Gizz-themed football shirts in the Bulgarian team colours; the back of one is emblazoned with “Nathan”, the name of the modular synth rack that looks like an old-fashioned telephone switchboard that the band have been consistently building and experimenting with on tour. “Every city we go to, they’re like, ‘Is there a modular synth place here?’” says Heriot, their photographer: the band – and particularly musician Joey Walker – add new bits to it like tourists collecting fridge magnets.

-

From left: Joey Walker and Stu Mackenzie building Nathan in Lisbon

On day two, an excellent free socialist architecture walking tour of the city that apparently usually draws five people attracts a crowd of 43 – largely Gizz heads – to the delight of the tour guide. Before the show, an American guy called Michael is going around the venue asking people what their first ever gig was, though it’s hard to imagine anyone having a better story than his: after his dad picked up some German hitchhikers who stayed for a month, to his mother’s chagrin, their parting apology was to take him to see Fleetwood Mac on the Rumours tour.

During the performances, Heriot is underneath Nathan, shooting upwards through Mackenzie’s legs, putting his battered Leica M6 – originally a war camera – to good use. Drugs may be illegal but weed, acid and MDMA are apparently flowing freely. And after a heavy rainshower before the show, fans everywhere (me included) are stacking it down the steep, slippery marble steps, many of which have no hand rails, sending drinks flying. (The venue’s health and safety doesn’t seem to have moved on since ancient times.) On the last night, we overhear an Australian man giving a local tips on how to know when the acid is kicking in.

As the final show of the run draws to a close, Walker says from the stage: “Thanks to our majestic crew for facilitating our bizarre-as-fuck behaviour.”

-

From left: Ambrose Kenny Smith, Cook Craig, Lucas Harwood, Mickey Cavs, Joey Walker and Stu Mackenzie at Lukiškiu prison

Part of that is rewarding the fans with a totally different setlist on each night of a single residency, not repeating any songs in a single city. “It’s not really sent over until half an hour before the show,” says Heriot, who has known the band for 10 years, has carte blanche to document their existence and also got their blessing to learn how to shoot on 16mm film for a forthcoming documentary. “They all know what to do, but it leaves that opportunity to step it up. You can see there’s a chemistry there where they don’t even have to talk, they’ve played with each other for so long and for so many hours. It’s super interesting to watch, and what makes it exciting to document and photograph.”

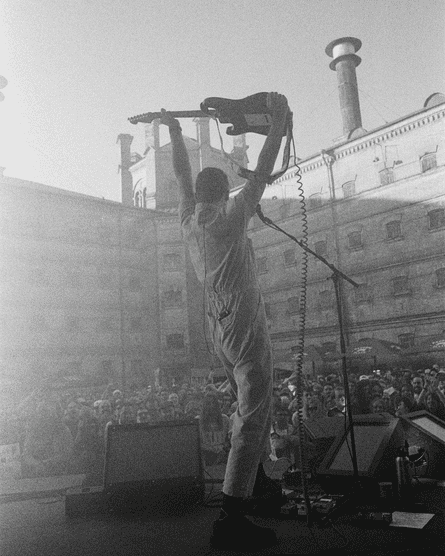

He talks about the classic “hero photograph” of a musician, where they’re caught mid-jump or in a triumphant pose. “The photo looks incredible – then you see them doing it again the next night. It happens every night in the same spot, at the same time.” Gizz’s constant deviation from any script means “you really have to respond to the moment, to be as tuned in as possible to what’s happening.” To aid that, Heriot wears an in-ear with the front-of-house mix. “It means I can really hear what’s happening on stage and chase their energy.”

Gizz entered proggy territory around 2016’s Nonagon Infinity, leading to a tightly structured live show that never stopped for breath. “We got to the end of the rainbow on that one,” says Mackenzie. “For us, at least, it got boring. And that’s when the setlist started to unravel, throwing in older songs. We had this back catalogue we barely ever played live – we should dig into this. We really noticed around that time that the audience slowly started to change in a nice way, and it became apparent that nobody cares if you make a wrong note.”

-

Performing at Lukiškiu prison

It dovetailed with the 34-year-old’s growing interest in connecting with people rather than shocking them. “People are interested in the humanity of that, and that’s quite a liberating feeling. It’s also something we still wrestle with on the daily – you get up there and you might as well be naked. It’s pretty intense, like – shit, I can’t remember this song we haven’t played in two years, we didn’t soundcheck it. But you work your way through it together, it forces you to look at each other and make music with each other.”

Previously, he said, he felt like a performer; now he feels like a musician. Gizz also don’t rehearse. “You have no choice but to figure it out as you go, you listen and you’re playing on the fly, creating in real time,” says Mackenzie. “It’s the best feeling. We’ve leaned into that more and more. This residency thing, part of the format is that we get to play seven hours or something of all different music – that’s like a dream to us.”

On the opening, title track of Phantom Island, one of Gizz’s pilots has landed on a mysterious desert island, experiencing “a symphony of delusion as my thoughts finally realise their purpose”. Amid loneliness and doubt, conspiracy and suspicion blooms. It feels like the kind of typically characterful reflection on modern life that Gizz have been writing in recent years.

In a grasping industry and an increasingly siloed modern life, their existence feels like an antidote to this sort of isolation: generous, communal, devoid of cynicism and pure of motivation. Their world is seductive: small egos, huge hearts, full of purpose. Old places can make you feel small, says Mackenzie, and so can big crowds, in the best possible way. “I know some people can get anxious in them, but I think it’s important. There’s something in the experience of going to a concert that is innately human, being around other people.”

2 months ago

33

2 months ago

33