Gaatha Sarvaiya would like to post on social media and share her work online. An Indian law graduate in her early 20s, she is in the earliest stages of her career and trying to build a public profile. The problem is, with AI-powered deepfakes on the rise, there is no longer any guarantee that the images she posts will not be distorted into something violating or grotesque.

“The thought immediately pops in that, ‘OK, maybe it’s not safe. Maybe people can take our pictures and just do stuff with them,’” says Sarvaiya, who lives in Mumbai.

“The chilling effect is true,” says Rohini Lakshané, a researcher on gender rights and digital policy based in Mysuru who also avoids posting photos of herself online. “The fact that they can be so easily misused makes me extra cautious.”

In recent years, India has become one of the most important testing grounds for AI tools. It is the world’s second-largest market for OpenAI, with the technology widely adopted across professions.

But a report released on Monday that draws on data collected by the Rati Foundation, a charity running a countrywide helpline for victims of online abuse, shows that the rising adoption of AI has created a powerful new way to harass women.

“It has become evident in the last three years that a vast majority of AI-generated content is used to target women and gender minorities,” says the report, authored by the Rati Foundation and Tattle, a company that works to reduce misinformation on India’s social media.

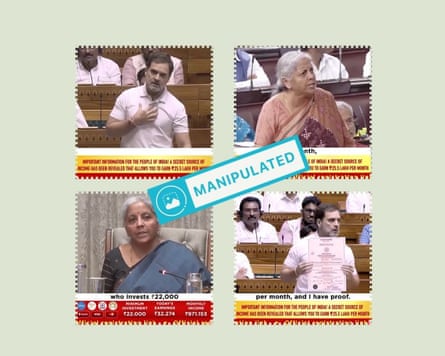

In particular, the report found an increase in AI tools being used to create digitally manipulated images or videos of women – either nudes or images that might be culturally appropriate in the US, but are stigmatising in many Indian communities, such as public displays of affection.

About 10% of the hundreds of cases reported to the helpline now involve these images, the report found. “AI makes the creation of realistic-looking content much easier,” it says.

There have been high-profile cases of Indian women in the public sphere having their images manipulated by AI tools: for example, the Bollywood singer Asha Bhosle, whose likeness and voice were cloned using AI and circulated on YouTube. Rana Ayyub, a journalist known for investigating political and police corruption, became the target of a doxing campaign last year that led to deepfake sexualised images of her appearing on social media.

These have led to a society-wide conversation, in which some figures, such as Bhosle, have successfully fought for legal rights over their voice or image. Less discussed, however, is the effect that such cases have on ordinary women who, like Sarvaiya, feel increasingly uncertain about going online.

“The consequence of facing online harassment is actually silencing yourself or becoming less active online,” says Tarunima Prabhakar, co-founder of Tattle. Her organisation used focus groups for two years across India to understand how digital abuse affected society.

“The emotion that we have identified is fatigue,” she says. “And the consequence of that fatigue is also that you just completely recede from these online spaces.”

For the past few years, Sarvaiya and her friends have followed high-profile cases of deepfake online abuse, such as Ayyub’s, or that of the Bollywood actor Rashmika Mandanna. “It’s a little scary for women here,” she says.

Now, Sarvaiya hesitates to post anything on social media and has made her Instagram private. Even this, she worries, will not be enough to protect her: women are sometimes photographed in public spaces such as the metro, and those pictures can later appear online.

“It’s not as common as you would think it is, but you don’t know your luck, right?” she says. “Friends of friends are getting blackmailed – literally, off the internet.”

Lakshané says she often asks not to be photographed at events now, even those where she is a speaker. But despite taking precautions, she is prepared for the possibility that a deepfake video or image of her might surface one day. On apps, she has made her profile picture an illustration of herself rather than a photo.

“There is fear of misuse of images, especially for women who have a public presence, who have a voice online, who take political stands,” she says.

after newsletter promotion

Rati’s report outlines how AI tools, such as “nudification” or nudify apps – which can remove clothes from images – have made cases of abuse once seen as extreme far more common. In one instance it described, a woman approached the helpline after a photo she submitted with a loan application was used to extort money from her.

“When she refused to continue with the payments, her uploaded photograph was digitally altered using a nudify app and placed on a pornographic image,” the report says.

That photograph, with her phone number attached, was circulated on WhatsApp, resulting in a “barrage of sexually explicit calls and messages from unknown individuals”. The woman told Rati’s helpline that she felt “shamed and socially marked, as though she had been ‘involved in something dirty’”.

In India, as in most of the world, deepfakes operate in a legal grey zone – no specific laws recognise them as distinct forms of harm, although Rati’s report outlines several Indian laws that could apply to online harassment and intimidation, under which women can report AI deepfakes.

“But that process is very long,” says Sarvaiya, who has argued that India’s legal system remains ill equipped to deal with AI deepfakes. “And it has a lot of red tape to just get to that point to get justice for what has been done.”

Part of the responsibility lies with the platforms on which these images are shared – often YouTube, Meta, X, Instagram and WhatsApp. Indian law enforcement agencies describe the process of getting these companies to remove abusive content as “opaque, resource-intensive, inconsistent and often ineffective”, according to a report released on Tuesday by Equality Now, which campaigns for women’s rights.

While Apple and Meta have recently taken steps to limit the spread of nudify apps, Rati’s report notes several instances in which these platforms responded inadequately to online abuse.

WhatsApp eventually took action in the extortion case but its response was “insufficient”, Rati reported, as the nudes were already all over the internet. In another case, where an Indian Instagram creator was harassed by a troll posting nude videos of them, Instagram only responded after “sustained effort”, with a response that was “delayed and inadequate”.

Victims were often ignored when they reported harassment to these platforms, the report says, which led them to approach the helpline. Furthermore, even if a platform removed an account spreading abusive content, that content often reappeared elsewhere, in what Rati calls “content recidivism”.

“One of the abiding characteristics of AI-generated abuse is its tendency to multiply. It is created easily, shared widely and tends to resurface repeatedly,” Rati says. Addressing it “will require far greater transparency and data access from platforms themselves”.

3 months ago

74

3 months ago

74