If your knowledge of Toni Basil begins and ends with her cheerleader-chanting smash hit Mickey, that’s just the tip of a very deep iceberg. By the time Mickey topped the US charts 43 years ago this week, in 1982, Basil had already spent four decades in the entertainment industry. The deeper you go, the more places you realise she was. When Elvis Presley sings “See the girl with the red dress on” in his 1964 movie Viva Las Vegas, and points across the dancefloor, the gyrating girl in the red dress is Basil. When Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper take LSD at the end of Easy Rider with two sex workers, one of them is Basil. When dance troupe the Lockers showcase their pre-hip-hop street dance moves on Soul Train in 1976, it’s six guys and … Basil. By the time of Mickey she had already worked with everyone from David Bowie to Tina Turner to Talking Heads, with more to come.

Basil has been-there-done-that in so many places, for so long, and over the course of our two-hour conversation she’ll casually drop asides such as “… so I went to see Devo with Iggy Pop and Dean Stockwell” or “… me and Bowie had just come from dinner with Bob Geldof, Paula Yates and Freddie Mercury” or “I was just at Bette Midler’s 80th birthday party, what a bash!” She’s now 82 years old but on Zoom, from her dance studio in Los Angeles, she doesn’t look much older than she did in the video for Mickey – and she looked like a teenager in that, even though she was 38 at the time. Her memory is perfectly sharp, too, and her energy levels are as high as ever, as she shares her packed life story with animated diction. If she has a secret to eternal youth, it’s that she has danced her whole life, and she still does, she says. “Dance is my drug of choice. You get high from it, and it gives you community.”

Basil’s brief pop career was, she explains, actually thanks to Manchester and the BBC. She signed to a British record label in 1979 to record her album Word of Mouth, which included a reworking of Kitty, an album track by forgotten British band Racey. Basil gave it a gender-switch, a new wave synth makeover and that unforgettable cheerleader chant – “I had to beg my record company to let me record it,” she remembers. “They thought it was a terrible idea; they didn’t know what cheerleaders were.” She made little films for a few of the songs, singing and dancing. “This was a year before MTV,” she explains. By chance, a couple of BBC producers, Ken Stevenson and Alan Walsh, watched them playing in a record shop in Manchester, “and they saw in the credits that I had choreographed and directed it all.”

They invited her to make a two-part special for the BBC, with more song-and-dance numbers and little comedy skits. The show plays like a lost time capsule of 80s kitsch: somewhere between punk, new wave and hip-hop; colourful, playful, subtly subversive, almost like an over-caffeinated kids’ cartoon. It was this that launched Mickey as a hit single – first in the UK (in March), then in Australia (a No 1 that July), then, after a new American recording contract and a new video (Basil wore her original high school cheerleader outfit), a No 1 in the US that December. “It took Britain, land of Boy George and the Beatles, to go, ‘Look at this. Let’s put this on television,’” she says. “In the US, they were like: ‘What is she thinking?’”

Basil really did have showbiz in her Italian American blood. “It never occurred to me that I would do anything else,” she says. “My mother’s side of the family were vaudevillian stars, kind of acrobatic comedians.” Her father was an orchestra leader, first in Chicago, then at the Sahara hotel in Las Vegas. “I stood on the side of the stage from 1947 to 1957 seeing a show every weekend; everybody from Josephine Baker to Nat King Cole to Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland.”

She was their only child. “They thought I was the centre of the earth. I was extremely spoilt. And I was really a good dancer. They saw what I had going, and they really pushed it.” Her teenage life was daily ballet classes and acting lessons, followed by go-go clubs every night, “dancing the pony, the mashed potato, all of that”. The tide was turning: the youth rebellion of the early 1960s was making older entertainers look stale and square. Basil was one of a handful of dancers who really knew what the kids were digging, so she soon picked up work dancing and choreographing. It sounds like a great time to be young, I suggest. “I think it’s always a great time to be young!” she replies.

Given all this, Basil wasn’t particularly fazed to find herself standing in for Ann-Margret and teaching Elvis Presley dance steps when she was just 20. “Being nervous around Elvis? He was part of the show-business family. I mean, I appreciated it was Elvis Presley, but not in that crazy fan way.” Or hanging backstage during the 1964 concert movie T.A.M.I Show, which she also choreographed. “We were in the green room with the Rolling Stones and Smokey Robinson watching James Brown, and the Stones realised, ‘Oh shit, we gotta follow him?’” Likewise the Rat Pack movie Robin and the Seven Hoods, where she played a chorus girl. “I started out in the back line, and the next day I was in the centre line. By the third day, I was front and centre.” Basil even features in a promotional featurette for the movie, chatting on set with Sinatra, Dean Martin and the gang. They were mostly gentlemen, she says. “Maybe Bing Crosby made a pass at me, but I don’t think I was so interested.” That seems to be another thing she was unfazed by: “I had directors making a pass at me, but it was never a pass that, if I was not reciprocal, I didn’t get the job.”

By the late 60s the tide had turned again, and Basil was part of the counterculture. Her boyfriend at the time was the actor Dean Stockwell, which brought her into the orbit of Dennis Hopper, Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda and artists such as Wallace Berman and Bruce Conner. Conner’s 1966 art film Breakaway consists of Basil dancing and singing the title song, which went on to become a sought-after northern soul track – Mickey was not her first rodeo.

That’s how she came to be in Easy Rider, plus other counterculture classics such as the Monkees’ Head, Five Easy Pieces (with Nicholson), and Hopper’s infamously erratic The Last Movie. Hopper was usually the overbearing presence in this gang, it seems. His intensity filled the room, she says. “He either hated something or loved it, there was no in between, which was quite entertaining, but he could be mad as a hatter.”

As for the drugs associated with this scene, Basil never really took to them. “Pot made me paranoid, to the point of passing [the joint] around and really not taking a toke out of it,” she says. “And at one point I was able to get some cocaine, which was pretty fabulous. I made a film in a week on cocaine! But it broke my skin out. So me with my vanity? Oh no!”

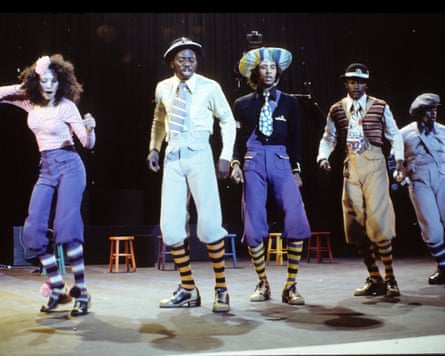

By the time this scene fizzled out in the early 70s, Basil was already on to the next thing. Dance had moved on since go-go, so she asked a girlfriend: “Find me the best dancer and have him call me. I need some classes.” The best dancer turned out to be a kid called Lamont Peterson, who put her on to the straight Black club scene in south Los Angeles, and Don “Campbellock” Campbell, who was inventing a new style of dance that became known as “locking”. “It was the most spectacular dancing I had seen since James Brown,” says Basil. “He did a lot of arms,” she goes through the moves on camera: “wrist-roll, point, five, slap. There was something of communication; the dancer could have a conversation with the audience.” There were also athletic leaps, down on to the knees or into splits, even somersaults. This was an individual, club-based style but, drawing on her vaudevillian instincts, Basil formed a stage troupe with Campbell and four other dancers called The Lockers. This was still pre-hip-hop, in the mid-70s, but you can see it prefiguring later street dance styles – like body popping, “waacking” and breakdancing. The Lockers toured with everyone from Sinatra to Funkadelic. “We changed the face of dance,” she says. “We showed audiences that street dance was an art form.”

Basil was also building a career as a choreographer. Bowie invited her to London out of the blue in 1973 to choreograph his forthcoming Diamond Dogs tour. His vision for it was more like rock opera: complex moving sets, costume changes, theatre lighting, dance numbers. It was intense; 13-hour days of rehearsals. “There was a lot of homework with Bowie.” She marvelled at his stamina. “David could do anything; as an actor, as a mover, he wasn’t a normal dancer – I mean, the guy didn’t even look normal, he just looked like this strange alien god. I always thought he should have been James Bond.”

This is what connects all the most impressive people she’s worked with, says Basil: “Their work ethic is just obsessive: pre-production, planning, rehearsals.” Turner was another. She approached Basil in the late 70s, when she was seeking to go solo. It was a vulnerable time for her, having effectively been in hiding since ending her infamously abusive marriage to Ike a few years earlier. After her high-energy moves with the Ikettes, Turner was after something more elegant, says Basil. But she certainly knew her stuff. In their first run-through Basil sat poised, ready to write down her feedback. “I watched the whole thing, and I realised I’d never put the pencil to the paper. It was just shocking to be in the same room with her, singing and dancing with the band. It was startling. And she does it all in high heels, and then, as soon as it’s over, she can hardly walk in the heels. But you’d never know it.” Basil worked with Turner right until her final 50th anniversary tour, in 2009. “She was an elegant queen, and yet she’s up in the girls’ dressing room, working on their weaves, fixing their hair.”

Basil’s pre-MTV videos also caught the attention of David Byrne, of Talking Heads, who asked her to direct a promo for their song Crosseyed and Painless – which featured her street dancer friends and none of the band – then, a year later, their classic Once in a Lifetime, for which she and Byrne researched films of people in trances and religious ecstasy to come up with his jerky, idiosyncratic dance style. “As a matter of fact, he was very hesitant about that,” she recalls. Before that, “I don’t think he really danced at all.”

Basil would go on to choreograph other acts, especially Midler, and films and TV shows, from American Graffiti to Sesame Street to Legally Blonde, right up to Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, for which she taught Margot Robbie and Leonardo DiCaprio their 60s moves. “She was the goddess of go-go,” Tarantino said of Basil, “She knows the era perfectly.” Perhaps better than he realised: Tarantino’s film harked back to the Manson family’s murder of Sharon Tate and her friends in 1969. “I knew Sharon and Roman [Polanski, her husband], we used to hang out,” she says. “I dated Jay Sebring!” Sebring, the celebrity hairstylist, was Tate’s friend and ex-partner, and was murdered alongside her that night. Basil dated him years before. “He and Gene Shacove were the two straight hairdressers in Hollywood. Straight hairdressers get laid as much as straight male dancers.”

Basil never married but seemingly had quite a few celebrity liaisons over the years, not least with her collaborators. “I worked with them through it all.” She remains cryptic on the details. “I worked with Bowie through it all. I worked with Jerry Casale [of Devo, who contributed tracks to Basil’s Word of Mouth album] through it all. I worked with Byrne through it all. Our relationships have always remained, no matter what, creative.”

Is she saying these were purely creative relationships? “No.” She’s not minded to go into detail, though. “You’re the Guardian and I’m not talking about my sex life!” she says mockingly, then adds: “It’s extremely erotic when it’s creative and it’s sexual. Oh my God, there is nothing more spectacular. And if you deliver work that is also spectacular, you don’t mind losing the sex, but you don’t want to lose the creative connection.”

Now she lives alone in “a wonderful house in Los Angeles” with her five cats and her dance studio next door. She still teaches students, judges street dance competitions globally and is regarded as a legend in the field. And she still hears Mickey echoing through the culture: in movies (most recently Die My Love), and in songs by the likes of Run DMC (It’s Tricky), Gwen Stefani (Hollaback Girl), Taylor Swift (Shake It Off), Charli xcx (Speed Drive) and, most recently, Blackpink singer Rosé’s hit single with Bruno Mars, Apt. “It’s kind of an anthem now. Here in America, if you’re a little cheerleader, you’re dancing to it.”

Her own taste of pop stardom might have been fleeting – follow-up singles to Mickey and a second album barely troubled the charts – but she doesn’t seem too bothered: “I never thought of it as anything but a time period. It was just a train ride. I was able to earn a living, I had fabulous, talented friends that were all doing something similar, but like Bowie, we all evolved. Dance styles change, music changes, so if you keep up with the trend, you change.”

2 months ago

33

2 months ago

33