Despite suffering heart attacks, strokes and the effects of diabetes, Gerard Baker can still easily lift an 80-lb bag of feed for the cows he raises on his south-east Montana ranch. On the sprawling 640-acre property of pine and cottonwoods, buffalo grass and blue grass, Baker drives out early in the mornings to feed his cows and think about what he could have done differently.

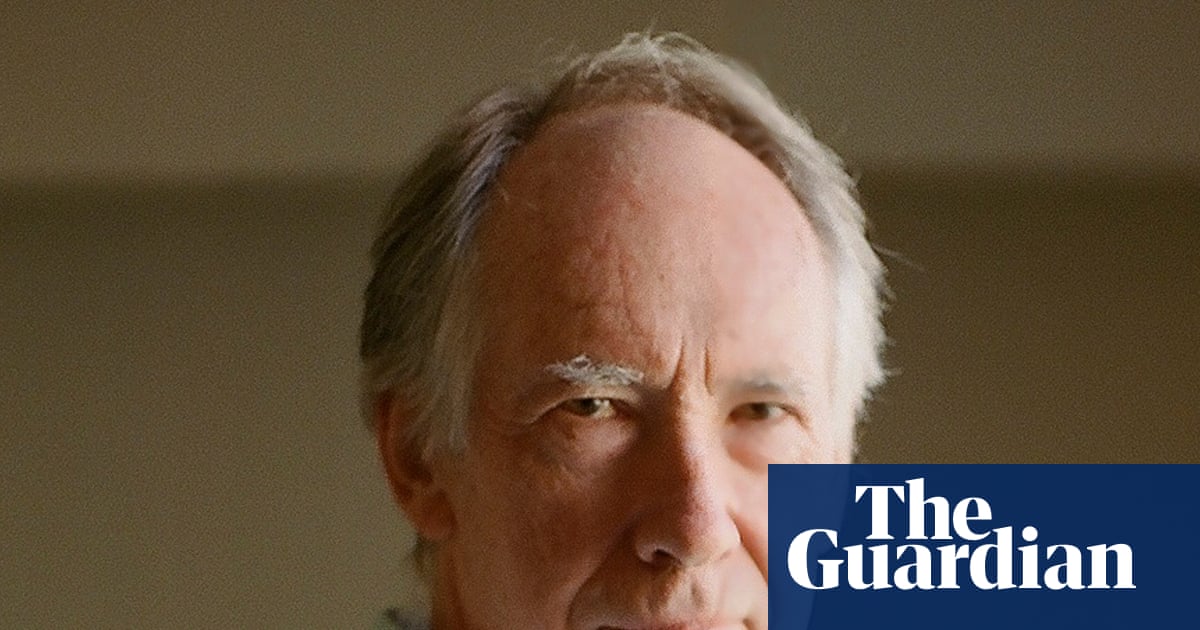

On 1 June 2004, Gerard Baker became the first Native American superintendent at Mount Rushmore national memorial, and his six years at the helm were both transformative and turbulent.

Mount Rushmore was first conceived by Doane Robinson, the South Dakota state historian, who wanted to build sculptures in the Black Hills that reflected the American west and attracted regional car tourists. When Robinson tasked the controversial artist Gutzon Borglum to lead the project, however, the idea metamorphosed from economics to politics, as Borglum decided to build a memorial to the American political system, which he deemed the apotheosis of western civilization. He envisioned portraits of four presidents who he called “empire makers”, and on 1 October 1925, Borglum held the memorial’s first dedication in front of over 3,000 spectators.

One hundred years later, the national memorial is a lightning rod of political and historical interpretation. In summer 2020, Donald Trump gave a speech at Rushmore that offered a narrow view of American history and the memorials and monuments meant to reflect that history. More recently, Rushmore has become a totem for Maga America, with legislation introduced to carve Trump into the granite. Yet the memorial stands on land that reflects the darker side of our nation’s past, a history the Trump administration is keen to erase.

The Black Hills, the Paha Sapa in Lakota, are sacred to the Lakota, and the US took the Paha Sapa from the Lakota Nation in early 1877, after the tribe had defeated George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn the previous June. The Lakota call the Black Hills the Heart of Everything That Is, and when the US stole the landscape of ponderosa pine and granite, it broke the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie and began a process to erase Native American culture and history.

During his six years as leader at Rushmore, Baker, who is now 71, worked to reintroduce this history at Mount Rushmore and expand the memorial’s interpretation to include stories and histories of the Indigenous American tribes who have called the Paha Sapa home for thousands of years. He hired local, Native American interpreters to tell their tribes’ stories; set up teepees to educate visitors and recruited hoop dancers to perform at Rushmore’s large auditorium to showcase Indigenous culture. For Baker, these efforts were the culmination of a career spent expanding the interpretation of our national parks.

While many of the millions of annual visitors to Mount Rushmore loved the new perspectives, others within the Black Hills were unsettled by this widened interpretive framework. They were debates, in hindsight, that presaged this current political moment.

Mount Rushmore national memorial is stewarded by the National Park Service (NPS), which is itself part of the US Department of the Interior (DOI). In an effort to “restore truth and sanity to American history”, Trump issued an executive order that took effect this fall and instructed the DOI to ensure memorials and monuments “do not contain descriptions, depictions, or other content that inappropriately disparage Americans past or living … and instead focus on the greatness of the achievements and progress of the American people”.

While this effort to sanitize American history at our national parks fits within the Trump administration’s broader goal to reshape American historical narratives, it runs counter to Baker’s struggles to make our national parks – to make Mount Rushmore – a more accurate reflection of our complex nation and history.

When Baker retired from the National Park Service in 2010, he was the highest-ranking Indigenous American to ever work in the organization. “I like to tell people that my first job in the Park Service was cleaning toilets and I worked my way down to management,” he once joked with me. Baker, who is Mandan-Hidatsa, was born on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota in 1953, the year the Garrison Dam opened along the Missouri River.

Garrison Dam was built to prevent flooding along our country’s longest river, and though everyone wanted to control the flooding, no one wanted their communities impacted by the proposed dams. As the least powerful citizens in North Dakota, the Indigenous Americans living on Fort Berthold Reservation watched as Garrison Dam flooded their homes, crops, graves, historical sites and generational memories. Eighty percent of the families living in Fort Berthold – including the Bakers – were forced to relocate; a traumatic experience Baker and his family never forgot.

Baker’s first job in the National Park Service was tending campgrounds at nearby Theodore Roosevelt national park. By summer 1974, Baker had switched to weekend patrol, and on Sunday evenings, he would witness the campfire theater and interpretive programs offered by the park rangers.

“And they would talk about – obviously Theodore Roosevelt – talk about the wildlife, talk about the cottonwood trees and asters, talk about natural resources and white cultural resources. And nothing about Indians. Nothing about Indians. And that was their territory. That was Hidatsa territory.”

Baker approached the park’s chief interpreter and asked if he could give a program, and she surprisingly agreed. Baker built a fire, dressed in traditional Hidatsa clothes, and set traditional music over the speakers as a crowd assembled. He wanted to almost magically emerge from behind a partition, and when he did so, dancing and spinning, he was shocked to see many of his relatives in attendance.

Though Baker was embarrassed to perform in front of his family, he grew committed to telling Native American stories within the largely white national park system. It was a commitment he brought with him to two critical leadership positions within the NPS. First, as superintendent at the Battle of Little Bighorn National Monument, where he received death threats for his efforts to tell the stories of the Indigenous Americans who fought against Custer in 1876. Later, as superintendent of Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, where he led the bicentennial of the expedition, emphasizing not only the two American explorers but also the Native peoples and villages affected by their journey west.

Still, these challenges paled in comparison with what he would experience at Mount Rushmore.

Days before Baker started as superintendent of Rushmore, he and his wife drove to a hotel in the Black Hills town of Custer. Baker, who is tall, physically imposing and always in braids, asked for a room and was told none were available. His wife, who is white, then went into the hotel, asked for a room, and returned with a key. It was a form of racism not uncommon in the Black Hills, an area of the US with a fraught history between Indigenous Americans and white residents.

Thirteen years after the US seized the Black Hills, in 1890, the Wounded Knee Massacre – in which nearly 300 Indigenous Americans, largely unarmed, were slaughtered by American soldiers – took place just south of the Hills. Before Mount Rushmore was even an idea, Native American tribes in South Dakota had their lands taken and were forced onto reservations, their children forced into residential boarding schools designed to stamp out Indigenous language and culture.

Under this historical backdrop, no one contested the building of a memorial to the US on sacred Lakota land. A century on from Mount Rushmore’s initial dedication, however, perspectives have changed.

As Native American political consciousness and activism grew in the 1960s and 1970s, many in the Native American community and beyond began to see Rushmore less as a reflection of American exceptionalism and more a reflection of the genocidal march west that killed millions of Native peoples. The memorial became – and remains – a source of deep, generational pain.

Baker was attuned to all this when he took the job.

“The Rushmore story is tough to tell,” Baker told me. “That is a bad, tough story to tell without people getting emotional. And mad and crying and everything else. And it’s still that way.”

Before Baker introduced Native interpretation, he had his rangers travel to nearby Indian reservations. In public forums, Baker and his team asked residents how Rushmore should be interpreted, and the answers – full of pain and forgotten history – brought some rangers to tears.

In summer 2005, a year into his tenure, Baker set up a singular teepee to the left of Borglum’s sculpture, a flat stretch of land partially shaded by the ponderosa pine. The teepee had been up for a couple of days when Baker noticed a problem with the flaps. Dressed in his National Park ranger outfit, Baker went to adjust the teepee when he noticed a small crowd form around him. He gave an impromptu interpretive talk about Native history and culture, about the people who live and had lived in the Paha Sapa for generations. It was the beginning of Native interpretation at Rushmore; and today, that singular teepee has grown into the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota Heritage Village, which still stands today.

Though Baker’s expanded interpretations were ultimately successful, he clashed with the Mount Rushmore Society – a local non-profit that supports and helps fund the memorial – whose leadership questioned Baker’s emphasis on Native interpretive programs and bristled against his confrontational style. The fighting took a toll on both his relationships and his body. Baker’s health deteriorated, and in November 2009, after years of strain, he suffered a stroke. When he looks back on those days now from his Montana ranch, Baker wonders if he could have been less forceful in his pursuit of change.

Yet Baker’s battles over the interpretive soul of Mount Rushmore strike a chord today, as the Trump administration aims to remove any historical complexity from our national parks and museums. These efforts to narrow historical perspectives at places meant to serve all Americans emphasize what Baker has always understood, what he always fought for – the power of interpretation.

“We have to look at what do the visitors want to hear when they come to a park like Rushmore,” he once told me. “And how do they want to leave? Well, most people want to come to a national park and leave with that warm, fuzzy feeling with an ice cream cone. Rushmore can’t do that if you do it the right way. If you do it the right way people are going to be leaving pissed.”

-

Matthew Davis is an award-winning journalist and author based in Washington DC. His latest book, A Biography of a Mountain: The Making and Meaning of Mount Rushmore (11 November 2025) marks the memorial’s 100th anniversary in 2025.

3 months ago

54

3 months ago

54