Four young women sit together, waiting for the phone to ring. When the call finally comes, their friend’s voice is crackly and hard to make out, but they wait patiently for the signal to improve so they can start discussing their chosen book.

Every Thursday, the five friends come together away from the disapproving gaze of the Taliban for a reading circle. They read not for entertainment but, as they put it, to understand life and the world around them. They call their group “women with books and imagination”.

Most of the women in the group meet in person, but Parwana*, 21, lives in a different district so has to join by phone. She was still a child when the Taliban pulled girls out of education, so didn’t get to finish school. Now, she says, her entire week revolves around books.

“When they banned us from attending school, I lost all hope. My mother encouraged me, but I knew things wouldn’t improve,” she says. “I decided to do something myself … and now I have this reading circle.”

This week, Parwana is leading a discussion on The Year of Turmoil, a novel by the Iranian writer Abbas Maroufi about a young woman named Noushafarin who finds herself trapped in an oppressive marriage. Set against the backdrop of turmoil in mid-20th-century Iran, its themes of repression, faith and patriarchal power resonate strongly with the women.

Although they’re inside, there’s a chill in the air, and steam rises from cups of green tea as Parwana’s voice comes through the phone.

“She represents women who have suffered, who have remained trapped, and who are oppressed by family and society in today’s Afghanistan,” says Parwana of the character. “From the very beginning, I identified with her; it was painful, very painful.”

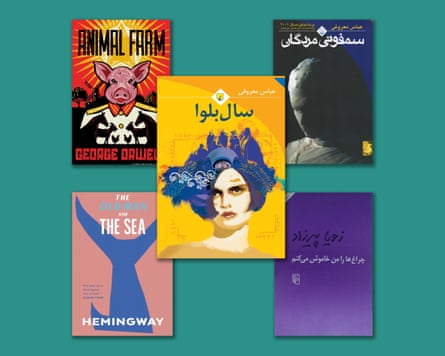

Most of the books the five women have discussed since they started the reading circle last June are classics, and most deal with issues of power, suffering, and the place of women, though they have embraced variety. The works they’ve read include George Orwell’s Animal Farm, Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, Zoya Pirzad’s I’ll Turn Off the Lights and Symphony of the Dead, also by Abbas Maroufi.

Most of the books can be found online and downloaded free, although occasionally they borrow books from libraries.

They meet every week for an hour-and-a-half at the home of one of the members, varying the location to avoid scrutiny in a country where women’s freedoms have been severely curtailed.

Parwana sometimes has to climb a hill to get a strong enough internet connection on her phone to download the book they are reading. But it’s worth it, she says, and she has the support of her elder brother, who has told her to keep at it, no matter what. “The excitement I feel for these sessions is indescribable,” she says.

All the women in the reading group had their hopes for an education dashed by the return of the Taliban. They are among the more than 2 million women and girls deprived of schooling in the four years since a ban was introduced, according to Unicef, which has warned of “catastrophic” consequences for the country.

“Reading has always been an integral part of my life,” says the group’s coordinator Darya*, 25, who was in her third year of a language and literature degree when the Taliban closed universities to women. “When I read, I feel as if I’m in another world – the characters, the places, nature. Sometimes I cry with the story, sometimes I laugh. But always, books have given colour to my life.”

Darya says The Year of Turmoil had a particularly strong impact on her. “This novel narrates years full of pressure and restriction. Noushafarin represents those who are caught in such times,” she says.

“Her situation mirrors the lives of people in today’s Afghanistan – people grappling with educational restrictions, social repression and political pressure. Like the characters in the novel, we keep hope alive through resistance and learning.”

Roya*, another member, explains the purpose of the circle this way: “Most women who accept oppression do so because they are unaware of their rights. The books we read are about suffering, choice and standing up to force – things we ourselves live with every day.”

Morwarid*, 22, says many women in Afghanistan resemble Noushafarin, who she sees as “trapped between tradition, religious power and social judgment”.

“She transforms from a silent woman into an aware human being. Her fate shows that, in such an environment, the very desire to choose is a form of resistance,” says Morwarid, who won a place at Balkh University in northern Afghanistan to study law and political science, but wasn’t able to take it up before the ban was introduced.

“The very night I was supposed to leave for Balkh, universities were closed to women,” she says. “I cried until morning. Life became dark for me. Through reading and this group, I gradually emerged from that nightmare.”

Her dream was to become a lawyer. Now, she says, Thursdays are the most important day of her week: “This circle has kept me away from many of life’s hardships.”

Tellingly, the book she has enjoyed the most is The Old Man and the Sea, a story of survival.

Morwarid stresses the importance of reading for women: “If a woman is aware, a family is aware. An aware woman raises aware children. The Taliban fear aware women. To confront the Taliban, one must become aware and grow – all together,” she says.

Outside, the restrictions continue. But in this small room, in the company of books, are young women for whom reading is a form of resistance.

* Names have been changed

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2