At the turn of the century there was a modest debate, mainly conducted on the letters pages of the newspapers – back then, still the prime forum for public discussion – as to when, exactly, the new millennium and the 21st century began. Most assumed the start date was 1 January 2000, but dissenters, swiftly branded pedants, insisted the correct date came a year later. As it turned out, both were wrong.

The 21st century began in earnest, at least in the western mind, on a day that no one had circled in their diaries. Out of a clear blue sky, two passenger jets flew into the twin towers of the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001 and so inaugurated a new age of anxiety – a period in which we have lived ever since.

The historian Eric Hobsbawm had already spoken of the short 20th century, which ran from the start of the first world war in 1914 to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. It was followed by the long decade of the 90s, which came to resemble a contented pause, a holiday from history, until it was rudely terminated on that bright New York morning.

The sight of it is still shocking. Nearly 25 years later, the portrait of an ash-covered sculpture, depicting a businessman and his briefcase, is as unsettling now as when it first appeared. Never mind that he was always a statue. The frozen Manhattan man, intact while everything around him lies in ruins, could be one of the petrified figures of Pompeii, a fully preserved emissary from a previous world: the world before 9/11.

For a while, it seemed as if the new era would be entirely defined by the 11 September attacks and the response to them. The “war on terror” declared by George W Bush threatened to remake the globe according to the preferences of the nation that, after the expiry of the Soviet Union, was now a solo hegemon: the US. After the invasion of Afghanistan, which would see US troops installed in the country for two decades, came the US-led conquest of Iraq and the toppling of Saddam Hussein – along with his statue – bringing death and devastation there and roiling both the Middle East and politics across much of the democratic world, including Britain.

The slogan of the hour was “the clash of civilisations” and plenty believed that struggle would dwarf all others in the new century. The reverberations of Iraq were certainly felt for many years, whether in the Arab spring, the birth of Islamic State or the persistent threat of violent jihadism. But that struggle has had to share space in the 21st century with others.

Not that that was obvious right away. At first, it seemed as if hope might edge out fear, that the new millennium might see change for the better. Barack Obama won a Nobel peace prize before he’d really done anything, in recognition of the optimism he stirred through his winning 2008 campaign, captured here in an image of the politician who, as he liked to remark, didn’t look like any other US president.

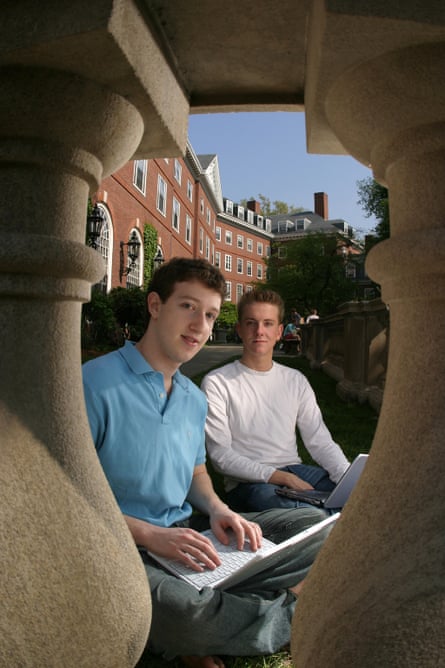

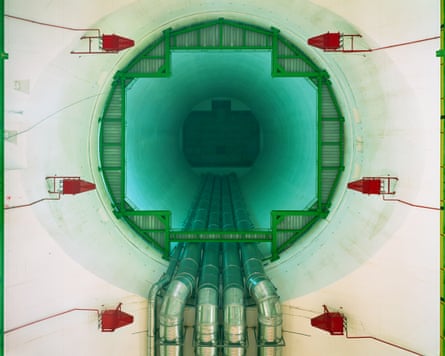

Easy as it was to deride that feelgood sentiment as “hopey, changey”, more vibe than reality, there was a lot of it about. Science and technology, especially, were thought to be full of promise. For some, that meant the excitement of the Large Hadron Collider, the biggest machine ever built. For others, it was the prospect of instant forms of social connection, delivered by a new breed of young, nerdy men able to turn 1s and 0s into magic. Just look at the image here of Mark Zuckerberg and fellow Facebook founder Chris Hughes, delightedly unaware that it was not the computer on Zuckerberg’s lap they had just opened, but Pandora’s box.

For a while, the optimism held, with tech and its birthing of social media celebrated as a remedy for all manner of ills, even the one that had announced the arrival of the century. The men of violence had brought 9/11, but a decade later Facebook and Twitter seemed to be harbingers of democracy, enabling those Arab spring uprisings, and others, against hated dictatorships.

It would not work out that way, and not only because of the long shadow cast by the war on terror. On another September day, in another steel-and-glass citadel of finance, there came another collapse, one whose impact is still felt. The implosion of Lehman Brothers was at the centre of a global crash that marked the end of an economic holiday from history that had endured since the 90s.

The stagnation that followed, with wages static or falling in real terms, created the backdrop for the political upheavals that marked the next two decades. Yet it was far from the only shock the world had to absorb.

The climate crisis was a constant throughout, as it is in this collection, making its presence felt in fire and flood, whether submerging Pakistan or New Orleans. (Bush’s catastrophic mishandling of that disaster is one more reason why he has been lucky in his latest successor: if it weren’t for the current occupant of the White House, W’s place as the most reviled US president of the early 21st century would have been assured.)

In 2020, we were struck by a global pandemic that can still seem like a collective bad dream. To look at a photograph such as the one here of an elderly Spanish couple, separated for a hundred days and by sheets of plastic, is to ask: did that really happen?

There are other pictures that look now like early warnings of trouble to come. The “separation wall” encircling the West Bank is a reminder that, after the failure of peace talks at Camp David in 2000, there has been a further 25 years of Israeli-Palestinian conflict, to add to the decades that went before, culminating in the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza that exploded on 7 October 2023 and has only recently paused. Similarly, the image from Ukraine in 2014 appears now like a premonition of the Russian invasion of 2022.

These have been turbulent years, roiled by culture wars and a long-delayed reckoning over race – how extraordinary now to recall that taking the knee began with a single athlete making a single gesture – and by vast movements of people. The agony of today’s refugee crisis is distilled in the sight of a two-year-old child, Alan Kurdi, face down on a beach. That cauldron of discontents was stirred further by tech platforms that were no longer about old friends reconnecting, but about strangers dividing against each other, their sources of information filtered along partisan lines, until they could be persuaded to believe almost anything, and usually the worst.

All of those currents fed into the movement that has defined the last decade or so, embodied by Boris Johnson and his notorious Brexit bus – a lie on wheels – and, of course, by the man who is the face of these times: Donald Trump. That movement is nationalist populism and it feeds on the many plagues of the 21st century, from stalled or declining living standards to social media, adroitly channelling unease and fear into hostility towards migrants, minorities and each other. Gaze upon the titans of tech come to pay homage to Trump as he returned to the White House in January and you see we are living through what the Italian writer Giuliano da Empoli calls “the hour of the predator”.

Yet there are enough images of wonder here to believe the rest of the 21st century might be different: look at the selfie taken by the Mars rover to be reminded of what we are capable of. The next 25 years are no more preordained than the last. Like the cameras that captured these extraordinary moments, they are in our hands.

Picture captions by Felix Bazalgette and Gabrielle Schwarz

Liberty Plaza, New York, 2001

By Susan Meiselas

When news came of the first plane crashing into one of the twin towers on 11 September 2001, Susan Meiselas cycled downtown with her camera – “moving toward what everyone else was desperately fleeing from”, with “no sense of the scale of what had happened”.

For her, this image stands out as a rare moment of “stillness amid the chaos”. It shows a lifesize statue of a businessman, Double Check (1982) by John Seward Johnson II, surrounded by debris in Liberty Plaza Park, across from the World Trade Center. Initially Meiselas couldn’t tell if it was a real person.

Today, she sees the statue as a symbol of the attempt to make sense of the enormity of 9/11 and its terrible aftermath: George W Bush’s “war on terror”. “A lot has happened as a consequence. Even the endless lines of security at the airport – these are small reminders of our distrust of each other.” GS

An Iraqi man comforts his son, 2003

By Jean-Marc Bouju

On 31 March 2003, an Iraqi man and his four-year-old child were arrested by American forces and taken to a prisoner of war camp near the southern Iraqi city of Najaf. French photojournalist Jean-Marc Bouju snapped the moment just after they had removed the man’s handcuffs, so he could comfort his distressed son.

The image won the World Press Photo of the year award, and captured for many the cruelty of the US’s invasion of Iraq. The hooded figure, attempting to preserve some humanity in an overwhelmingly hostile situation, foreshadows the infamous images of abused prisoners taken by American soldiers in Abu Ghraib prison, which would hit the headlines not long after. FB

Toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue, 2003

By Sean Smith

The image of Saddam Hussein’s statue being pulled down in Baghdad as American forces entered the city on 9 April 2003 became one of the iconic images of the war. It was promoted by the Pentagon as a symbol of Iraqis joyously greeting the overthrow of their hated dictator.

“I’m happy with the picture,” photographer Sean Smith says, “but not with things that may be ascribed to it – as a defining moment, say, because it wasn’t.” Even at the time, Smith felt “uneasy about becoming part of a false narrative”. He had been in Baghdad for months, as war had inched closer, and got to know many Iraqis. He knew the situation was more complex: “This wasn’t the liberation of Paris.” Most of the crowd that day, he remembers, were journalists staying in an overlooking hotel. “It was getting to their deadline time,” he remembers, “and they wanted a headline.”

Looking back, Smith is also saddened by the illusion of finality the photograph represents. When he returned to Iraq for work years later, one conversation about the invasion stuck with him. When an American soldier argued that it had been necessary for the freedom of the Iraqis, an Iraqi interpreter replied, “All I know is that everyone knows someone who’s died.” FB

Separation Wall, West Bank, 2004

By Alessandra Sanguinetti

It is a symbol of one of the most enduring conflicts of the century. In 2002, during the second intifada, the Israeli government started to build what is known as the Separation Wall: a barrier between Israel and the West Bank, which it has occupied illegally since 1967. This image shows children dwarfed by an eight-metre-high section of wall at Abu Dis, a Palestinian village in the suburbs of Jerusalem cut off from the rest of the city. The permits Palestinians need to cross the wall are hard to obtain, so movement is severely restricted.

The barrier, which has been deemed illegal by the International Court of Justice, was “presented as a security measure”, explains Emma Graham-Harrison, the Guardian’s Middle East correspondent, after a spate of suicide bombings targeting Israeli civilians. “However, it also functioned as both a land grab and a key step in enforcing separation. In some ways, it was a template for what Israel attempted to do with its fence enclosing Gaza: the idea that you could contain Palestinians physically without having to engage with them as fellow human beings or consider their political aspirations.” GS

Facebook founders Mark Zuckerberg and Chris Hughes, 2004

By Rick Friedman

“I got a call from an editor,” Boston-based photographer Rick Friedman recalls: “‘I need you to go over to Harvard and photograph these two kids with their computers.’” It was 14 May, a few months after Zuckerberg and Hughes had founded a social media site that, in its earliest iteration, invited students to rate the attractiveness of female classmates. Friedman recalls

the young pair were “very agreeable”, but also remembers thinking, “Is this some kid trying to get a date with his computer?” FB

Chicken processing plant, 2005

By Edward Burtynsky

It is sometimes said we are living in the Chinese century. Rapid industrialisation has seen China grow into an economic superpower – the “world’s factory” –accounting for up to 30% of global manufacturing output. Edward Burtynsky, whose acclaimed photographs document the effects of human industry around the globe, began working there in 2002. On one visit, struck by the number of chicken farms, he became curious about China’s food industry.

This image shows one of the country’s largest poultry-processing facilities, the Jilin Deda factory in Dehui city, where products were being prepared for export to Japan. “I’m always trying to find ways to represent in one frame the larger-than-life scale of what’s happening,” Burtynsky says. GS

Disaster girl, 2005

By Dave Roth

The concept of a meme as a self-replicating nugget of information was first popularised by Richard Dawkins in the 1970s in the context of genetics. But it was in this century that memes took off online, and became household names.

This image, declared “one of the most famous memes in history”, has humble origins. In 2005, Zoë Roth, AKA “Disaster Girl”, and her amateur photographer father were watching a local fire department training exercise, in which a donated house had been set on fire. Her father told her to smile and snapped the image. Drawn to the “evil” smile, people Photoshopped in other disasters – the Titanic, the Hindenburg. FB

Man during Hurricane Katrina, 2005

By Robert Galbraith

“George Bush does not care about Black people,” a 28-year-old Kanye West announced during a telethon to raise money for disaster relief in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Making landfall on the Gulf coast on 29 August 2005, it flooded 80% of New Orleans, killing 1,500 people and displacing roughly 1.5 million – but it was the deeper faultlines in American society, brutally revealed by the disaster, that came to define it.

As former MP Oona King, who visited the city shortly after the disaster, wrote, “The remarkable thing about Hurricane Katrina was that, like a bolt of lightning, it clearly and unavoidably illuminated the chilling impact of race.” FB

Paris, Lindsay and Britney behind the wheel, 2006

Photographer unknown

“This photo became the moment that defined an era,” wrote Paris Hilton on Instagram in November 2024, marking the 18th anniversary of this famous paparazzi shot of her with Lindsay Lohan and Britney Spears at the height of their fame, crammed in the front seat of Hilton’s car outside the Beverly Hills hotel. The photo was splashed across the papers; in the New York Post, it ran with the headline “Bimbo Summit”.

At the time, it was the quintessential image of 2000s celebrity glamour. All three women have since spoken out about their treatment by the media: the misogynistic scrutiny and judgment that spread far beyond celebrity circles. “They loved pitting women against each other,” Hilton has said. “It was so vicious.” GS

Rangers taking away a mountain gorilla, 2007

By Brent Stirton

The Democratic Republic of Congo’s Virunga national park, Africa’s oldest conservation area, is exceptionally biodiverse – and one of the most dangerous places to work. Since 1996, more than 200 rangers have been killed in a series of conflicts.

Photographer Brett Stirton took this picture after seven rare mountain gorillas were killed by hostile gunmen wanting to warn rangers not to disrupt illegal charcoal manufacturing in the area. Locals and park workers carried the bodies to a burial site. “Everyone was silent,” Stirton recalled later. “It was very reverent.”

Not all is lost. Last year, analysis published in the journal Science found conservation efforts around the world were helping stem the decline of biodiversity. “Our results clearly show there is room for hope,” one co-author said. FB

Large Hadron Collider, 2007

By Simon Norfolk

One of this century’s biggest scientific discoveries took place in the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, which opened at Cern in Geneva in 2008. This photo was taken when construction was under way.

Still the largest machine ever built, it consists of a 27km ring of superconducting magnets in a tunnel 100 metres underground. The magnets, chilled to a temperature lower than in outer space, are used to propel high-energy particle beams into collisions. By studying the results of these, particle physicists hope to answer questions about the essential workings of the universe. In 2012, they made a major breakthrough: the discovery of the Higgs boson, the so-called “God particle”. GS

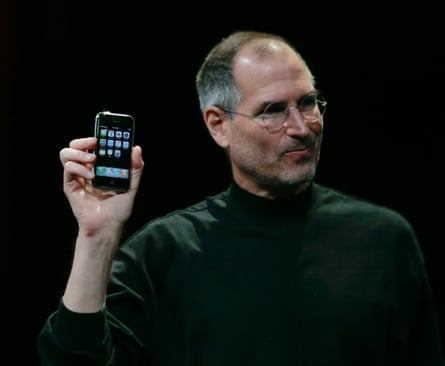

Steve Jobs with the first iPhone, 2007

By Kimberly White

In January 2007, Steve Jobs unveiled the first iPhone. “We are all born with the ultimate pointing device – our fingers – and iPhone uses them to create the most revolutionary user interface since the mouse,” the Apple CEO said. (For his demo, seen here, he had to follow a carefully planned “golden path” to avoid glitches; the software wasn’t yet finished.)

The touchscreen smartphone was released six months later, totally transforming the way we communicate. Today more than 1.4bn iPhones are in use globally. GS

Lehman Brothers staff, 2008

By Kevin Coombs

This photo of staff at the Lehman Brothers offices in London’s Canary Wharf was taken on 11 September 2008. Over the past year, the global financial system had been showing cracks. Now Lehman was in trouble, with its share price plummeting and rumours of a buyout.

“This meeting was called just before lunch,” said Gwion Moore (back left, minus the grey-suit banker trousers because his work clothes were at the cleaner’s). “A couple of senior bankers made a speech, saying, ‘We’re not going bankrupt, get back to work.’”

Four days later, Lehman did go bankrupt. “Trust evaporated and funds stopped flowing around the world,” says economic historian Catherine Schenk. What followed was the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. “It reminded us that, as in 1930, failures in the richest countries could spark a financial crisis that had repercussions in markets everywhere.” GS

Construction of the Burj Khalifa Tower, Dubai, 2008

By Philippe Chancel

Shown here in the last stages of its construction – and already towering over everything that surrounds it – the Burj Khalifa in Dubai has held the record for the world’s tallest building since opening its doors in January 2010. The neofuturist mega-scraper, with its 163 floors reaching 828 metres high, is not just a dizzying feat of engineering: it’s a symbol of the equally dizzying, oil-fuelled rise of the Gulf states in the 21st century.

In this era of expansion, flashy development projects have become a major tool of soft power: what the critic Rowan Moore has called a “cultural and architectural arms race”. The race is still on: the Burj Khalifa is soon to be eclipsed by the Jeddah Tower in neighbouring Saudi Arabia, which is scheduled for completion – with a height of 1,000 metres – by 2028. GS

Barack Obama on the campaign trail, 2008

By Damon Winter

“It was one of those moments that gets stuck in your head,” Damon Winter recalls. “Part of it was the irony that a memorable photo could come from such a banal setting – a podium in front of an American flag.” Yet everything lined up, from the shaft of light to Obama’s smile, and today the image captures something of the optimism and dynamism of his 2008 campaign – qualities absent from many other campaigns of the century. “It was a very optimistic time,” Winter says. “The country was experiencing this momentous change.”

Unlike other politicians Winter had covered, Obama “seemed like the same person on stage as he was when interacting with people. It seemed to me that he was really interested in people.” FB

Northern lights over the Eyjafjallajökull volcano, 2010

By Lucas Jackson

In spring 2010, after 187 years of silence, the Eyjafjallajökull volcano on the south coast of Iceland began a powerful eruption. It spewed fine volcanic ash high into the atmosphere, which began blowing towards the UK and western Europe. Almost all flights in the region were grounded due to fears that the ash would clog and stall jet engines.

Stranded in Iceland, photographer Lucas Jackson was able to capture this spectacular image of the northern lights playing over the erupting volcano. “When you’re a photographer,” he told the Guardian in 2010, “it’s really rare to actually be exactly where you want to be to take the shot. We were laughing about how crazy it all was.” FB

Pakistan floods, 2010

By Daniel Berehulak

In the summer of 2010, record-breaking rains led to extreme flooding in Pakistan. At the peak, one-fifth of the country was submerged. Nearly 2,000 people died and more than 20 million were affected, with homes and crops lost. Though unprecedented at the time, such severe flooding has since become a recurring event, including this summer.

As temperatures rise across the world, floods are becoming more frequent and intense. Unsurprisingly, poorer nations and communities are most affected. But, as UN secretary general António Guterres warned earlier this year, “No country is safe.” GS

Fukushima disaster, 2011

Photographer unknown

On 11 March 2011, a massive 9.0 undersea earthquake off the north-east coast of Japan triggered a tsunami that killed an estimated 20,000 people. More than a million buildings were damaged, including the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, where three reactors went into meltdown after flooding of the power supply disabled the cooling systems. It was the worst nuclear accident in history after Chornobyl.

Several workers were injured in explosions at the facility and more than 100,000 people in the wider region were evacuated to avoid radiation exposure. It’s estimated that 2,313 “indirect deaths” resulted from physical and mental stress, and that 29,000 people remain displaced. GS

Tahrir Square, 2011

By Moises Saman

The central Cairo roundabout known as Tahrir Square became the symbolic centre of the Arab spring in early 2011, though the movement itself had began the year before in Tunisia, after market seller Mohamed Bouazizi, a target of government harassment and corruption, set himself on fire outside a governor’s office.

“The Arab world was ripe with hope,” wrote Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018. Yet “these expectations were quickly shattered”. The assassination of Khashoggi that year, on the orders of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, reflected the wider slide into violence: Syria, Libya and Yemen have since suffered years of brutal civil war, and Egypt remains under the iron-fisted rule of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who came to power after the protests. FB

Boy in Liberia being treated for Ebola, 2014

By Daniel Berehulak

From late 2013 to 2016, the worst Ebola virus outbreak in history killed more than 11,000 people in the west African countries of Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. The fatality rate for recorded cases was 40%, attributed to poor standards of care, mistrust of medical authorities and an international response prioritising containment over treatment.

Daniel Berehulak photographed James Dorbor, eight, being carried into a clinic in the Liberian capital of Monrovia in September 2014; his health had deteriorated during a three-hour wait to be admitted. His father was not allowed to embrace him when medical staff finally took him in, carrying him, Berehulak said, “like he was a bag of garbage”. GS

Migrants above a golf club in Morocco, 2014

By José Palazón

In 2014, Melilla – a tiny slice of Spanish territory in Morocco – became emblematic of the rise of “Fortress Europe” policies in the 21st century. Human rights activist José Palazón captured the moment a group of men attempting to cross Melilla’s border became stuck on a razor wire fence for hours while Spanish golfers continued their game below. Eight years later, Melilla would become the site of a massacre in which at least 37 people trying to cross into Spain were killed by border guards.

Palazón shared his photo on Twitter, with the caption: “Immigrants on the fence, expulsions and a game of golf. Only in Melilla.” The surreal image of inequality quickly went viral. “It seemed like a good moment to take a photo that was a bit more symbolic,” he later said. FB

Priest at Ukraine’s Maidan protests, 2014

By Jérôme Sessini

Russia’s devastating war on Ukraine can be traced back to “Euromaidan” – the anti-government protests, centred in Kyiv, that began in November 2013 after then president Viktor Yanukovych gave in to Russian pressure and withdrew from an agreement that would have brought the country closer to the EU. On the uprising’s bloodiest day, 20 February 2014, Jérôme Sessini, who had arrived just a day before, documented what he saw – “not even thinking about the danger” – including this Orthodox priest blessing protesters at a barricade. More than 50 of them were shot dead that day. GS

Oscars selfie, 2014

By Ellen DeGeneres

The origins of the term “selfie” are humble: an Australian man posting a substandard picture of his bruised lip to an online forum in 2002. “Sorry about the focus,” he wrote. “It was a selfie.” The next year, sales of phones with front-facing cameras began to increase and by 2013 “selfie” was Oxford Dictionaries’ word of the year.

Organised by Ellen DeGeneres at the Oscars, this selfie broke the internet. Eleven years on, it might be cursed: Kevin Spacey would face damning sexual abuse allegations, Brangelina broke up. FB

Italian rescue, 2014

By Massimo Sestini

The number of people risking crossing the Mediterranean to Europe, fleeing wars and persecution in the Middle East and Africa, rose dramatically in the mid-2010s. In 2013, the Italian government launched its search-and-rescue operation Mare Nostrum, after hundreds died in two shipwrecks off Lampedusa.

Shot from a helicopter, Massimo Sestini’s image shows 500 people on a boat 25km from Libya’s coast, before they were rescued by Italy’s navy as part of an operation controversially halted that year. At least 20,000 have died or disappeared in the Med since. GS

The death of Alan Kurdi, 2015

By Nilüfer Demir

On 2 September 2015, photojournalist Nilüfer Demir saw the body of a toddler, Alan Kurdi, on a beach near Bodrum, Turkey. “There was nothing left to do for him,” she said later, “except take his photograph. And that’s exactly what I did.”

Alan was born in Syria in 2012. His family had been trying to reach Greece, but soon after their boat launched, it overturned and Alan and his mother drowned. “I was holding my wife’s hand,” his grief-stricken father later told the media, “but my children slipped through my hands. It was dark and everyone was screaming.”

Demir’s shocking image quickly spread. But, despite protests, a spike in donations to charities and western governments promising to do more, the Med remains the world’s deadliest border. FB

Caitlyn Jenner, 2015

By Annie Leibovitz

It was a high point in the movement for trans visibility. In June 2015, Caitlyn Jenner made her public debut in a portrait by Annie Leibovitz on the cover of Vanity Fair. It instantly had positive support and Jenner became the fastest person to hit 1 million Twitter followers, before facing a backlash when she came out as a Trump voter.

Since then, trans rights have been rolled back in the US and UK, but support remains strong. Earlier this year, the world’s largest trans pride march took place in London, with a 100,000-strong crowd. GS

Usain Bolt’s Olympics “triple triple”, 2016

By Cameron Spencer

“There you go, I’m the greatest,” said Usain Bolt when he achieved an unprecedented three consecutive Olympic golds (in 2008, 2012, 2016) in three races. Here, in the Rio 100m semi-final, “Lightning Bolt” seems to have found time to flash the camera a smile. He was in fact checking whether the runner to his left was catching up: “I saw I had him covered, and I smiled.” GS

The Brexit bus, 2016

By Jack Taylor

Brexit is, for many, the ground zero of what Marina Hyde called “an age of gathering chaos and rising disbelief” in the UK.

The “Brexit bus”, reportedly masterminded by Dominic Cummings but closely associated with Boris Johnson, became the subject of bitter arguments and a symbol of the chaos that has engulfed the UK since. Its slogan, claiming the UK sent £350m a week to the EU, was disputed, with the UK Statistics Authority deeming it “a clear misuse of official statistics”. Research by the Nuffield Trust has shown Brexit has in fact put unprecedented strain on the NHS. FB

Colin Kaepernick taking the knee, 2016

By Marcio José Sánchez

On 1 September 2016, during a San Francisco 49ers pre-season game, the quarterback Colin Kaepernick kneeled while America’s national anthem was played, in protest at police violence against Black people. His gesture was adopted by teammates – this photo shows him with Eli Harold and Eric Reid – then spread across the world, becoming linked to the Black Lives Matter protests that erupted in spring 2020. The gesture was highly controversial: Kaepernick was ousted from the league a year later and has never again played for an NFL team. FB

An assassination in Turkey, 2016

By Burhan Ozbilic

“We die in Aleppo, you die here,” shouted Turkish off-duty riot squad officer Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş after killing the Russian ambassador to Turkey, Andrei Karlov, at a gallery in Ankara, in protest at the actions of the Russian military in Syria. Soon after photographer Burhan Ozbilic snapped this unsettling image. Altıntaş was shot and killed by police. FB

Women’s March, 2017

By Bryan Woolston

In January 2017, the day after Donald Trump’s first inauguration as president, millions of women gathered across the world – including 500,000 in Washington – mobilised by his misogyny and sexual assault allegations. It was one of the largest single-day protests in US history, and nine months later its energy fed into the #MeToo movement, which began as a disquieting story of one Hollywood producer’s abuse of women and soon turned into a global reckoning. GS

Amazone, 2017

By Andreas Gursky

In 2017, the eminent German photographer Andreas Gursky, known for his vast, detailed, era-defining landscapes, trained his camera on an Amazon warehouse in Arizona packed full of goods destined for customers. This century has seen internet shopping go from a niche experiment – in 2000, the Guardian reported that anxieties about postage time had led to a “collapse” of online pre-Christmas book sales – to one of the most common ways to make a purchase. FB

Sophia the Robot, 2017

By Giulio Di Sturco

“It was super weird,” recalls Giulio Di Sturco of his visit to a Hong Kong lab to photograph Sophia the Robot. “Pieces of robots everywhere, five guys working like mechanics – to think the future might be built in this kind of space.”

The idea that Sophia represented a major leap in AI was big news: the next year, she became a citizen of Saudi Arabia – the first robot to be granted legal personhood anywhere. There were sceptics, however, and ChatGPT’s arrival in 2022 might suggest the future of AI is in chatbots and datacentres instead. But Di Sturco believes the humanoid robot’s time is still to come. “They were on the edge of something interesting,” he says. FB

Megan Rapinoe, 2019

By Franck Fife

After decades in which their game was dwarfed by men’s, women are winning fans for their playing and inclusivity. Megan Rapinoe’s victory pose after scoring for the US in the 2019 World Cup went viral: a symbol of both her athleticism and her advocacy on issues including LGBTQ+ rights and mental health. GS

Stormzy headlining Glastonbury, 2019

By Samir Hussein

“This is the best night of my entire life,” a 25-year-old Stormzy told the crowd during his historic set at Glastonbury in 2019, as the first Black British solo act to headline the festival. Wearing a Banksy-designed union jack stab vest, Stormzy crafted a set that both celebrated Black British culture – with guest performances from Ballet Black, WAR collective and Dave – and critiqued racism in the UK. Praised by everyone from David Lammy, Zadie Smith and Jeremy Corbyn to Adele and Ghetts, the performance went out of its way to educate its audience and reference the many acts that had come before to make it possible. “This was about arrival,” Smith wrote in the New Yorker, “of a king and his court and the many, many people who have hoped for this day.” FB

Covid kiss, 2020

By Emilio Morenatti

This photo shows the emotional reunion of Agustina Cañamero and Pascual Pérez, a couple in their 80s, in a nursing home in Barcelona in June 2020. Husband and wife had been separated for 102 days in the first lockdown – their longest time apart in 59 years of marriage. The image has come to symbolise how lives worldwide were upended by Covid.

The global health emergency was declared over in May 2023, and may feel like a distant memory. Yet more than seven million people have died to date, and many others are dealing with grief or long-term health issues. “Most of my generation have been affected in deep, developmental ways and that’s going to affect us for ever,” 21-year-old student Eoin O’Loughlin told the Guardian, in a 2023 series on the “Covid Generation”. GS

Storming of the Capitol, 2021

By Victor J Blue

On 6 January 2021, in the wake of Joe Biden’s election win, a crowd began to peel off from Trump’s fiery speech in which he accused the Democrats of stealing the election from him. Photographer Victor J Blue followed them as they broke into the Capitol buildings, and took this picture after they had been expelled – police officers, running out of pepper spray, were letting off fire extinguishers in an attempt to discourage protesters from breaking back in, which accounts for the “smoke” at the centre of the photo. FB

Life on Mars, 2021

By Perseverance

Was there once life on Mars? And could the planet, as Elon Musk believes, offer us a home when Earth becomes uninhabitable? It’s no surprise its exploration has been the dominant story of the 21st-century space race so far. Nasa’s Perseverance rover landed in February 2021, searching for signs of past life, so we can better understand the planet’s habitability.

This selfie, taken in 2024, is “such a nice encapsulation of what Nasa’s mission is all about”, says project scientist Katie Stack Morgan. Stitched together from 62 images (which is why the rover’s arm is missing), it shows Perseverance alongside the helicopter Ingenuity – the first aircraft to complete a powered, controlled flight on another planet. As for colonising the Red Planet, Stack Morgan points out we might first “ask whether we have been good stewards of our own planet”. GS

Greek wildfire, 2021

By Konstantinos Tsakalidis

“At that moment,” said 81-year-old Panayiota Kritsiopi, “I was shouting not only for myself, but for the whole village.” She was photographed as a huge wildfire on the Greek island of Evia forced thousands to flee and eventually burned more than half the island. Miraculously, Kritsiopi’s home would be spared; the fire reportedly stopped a metre from her house.

That year was quickly surpassed by 2022, then 2024, as Europe’s hottest on record, while this summer saw the worst wildfire season in European history. FB

Activists throwing soup at Van Gogh, 2022

Photographer unknown

“It was surreal,” recalls Just Stop Oil activist Anna Holland (right) of the day they and Phoebe Plummer approached a Van Gogh painting in the National Gallery, London, can in hand. “Almost before I knew it, we were throwing the soup.”

The stunt was part of a wave of climate action that has flourished this century, focused on symbolic targets such as this (safely protected behind glass). Though the pair were sentenced to prison under Britain’s increasingly draconian protest laws, they inspired fellow soup throwers worldwide. FB

The death of Queen Elizabeth II, 2022

By Ben Stansall

The queen’s death on 8 September 2022, at 96, ended a 70-year reign – the longest of any UK monarch.

Some 250,000 people joined the (very British) queue to see her lying in state ahead of the funeral, itself watched by 29 million TV viewers in the UK.

Here, her son, Charles III – at 73, the oldest person to succeed the throne – walks beside her coffin in Westminster Abbey. His grief is palpable, but beyond loss there is uncertainty: what next? GS

IVF rhino foetus, 2023

By Jon A Juárez

In March 2018, tragedy struck: Sudan, the last northern white male rhino, died. With only two females left, the species was functionally extinct. Then, a flash of hope: a foetus created using sperm taken from males before they died.

Sadly, the mother died of an unrelated infection. But tests showed the tiny foetus would probably have survived. Said photographer Jon A Juárez, “Though the story is bittersweet, the foetus proves the science works. If we support scientists’ efforts, we can still correct our course and make the planet a better place.” GS

Taylor Swift’s Eras tour, 2024

By Emma McIntyre

There was a period when Taylor Swift’s Eras tour – 149 shows in 51 cities over 21 months – seemed like it would never end. Neither did the appetite of her global fanbase, who packed out stadium after stadium for 3.5-hour performances of Swift’s greatest hits. When the international juggernaut finally concluded in December 2024, it was the highest-grossing concert tour of all time: more than $2bn in ticket sales. Her supremacy was confirmed.

The success of the tour also reflected the post-pandemic boom in major live music events, driven by fans craving joy and connection, as well as by artists seeking to supplement their incomes in the era of streaming. Meanwhile, it’s often said that our century has seen the death of the monoculture. Swift, it seems, is one of the last stars standing. GS

Trump assassination attempt, 2024 …

By Evan Vucci

“Let me get my shoes,” were Trump’s first words to the Secret Service agents bundling him away, after a sniper’s bullet grazed his ear. It was what he said next, however, fist raised, that sealed the moment in history: “Fight!” The image galvanised his supporters and injected new energy into his campaign. Coming just weeks after Joe Biden’s disastrous debate performance, this pivotal moment convinced commentators on both sides of the political spectrum that a second presidency was within his grasp. FB

… and tech leaders at his inauguration, 2025

By Saul Loeb

It is a defining image of power in 2025: Mark Zuckerberg, Lauren Sanchez, Jeff Bezos, Sundar Pichai and Elon Musk in the front row at Trump’s inauguration (Apple CEO Tim Cook is out of frame).

The tech bosses – of Meta, Amazon, Google and Tesla – are collectively worth almost $1tn, a figure that reflects the sharp increase in inequality globally this century.

The image also captures the political journey the US tech sector has been on, from darling of the left to throwing in its lot with the Maga right. FB

1 month ago

40

1 month ago

40