The news that a child damaged a £42m Mark Rothko painting at a museum in Rotterdam last month had me wondering how I’d feel if my toddler was the culprit. The work, Grey, Orange on Maroon, No 8, sustained small, superficial scratches to the lower part of the painting during an “unguarded” moment, which, while not a disaster, does mean it will have to be taken off display and restored. It comes less than a year after a four-year-old boy smashed a 3,500-year-old jar at the Hecht Museum in Israel.

Honestly, I’d be mortified. Not embarrassed for my child, who is too little to understand, but because as his parent I had taken my eye off the ball. I would blame myself. I’d also be terrified I would be made to pay for it.

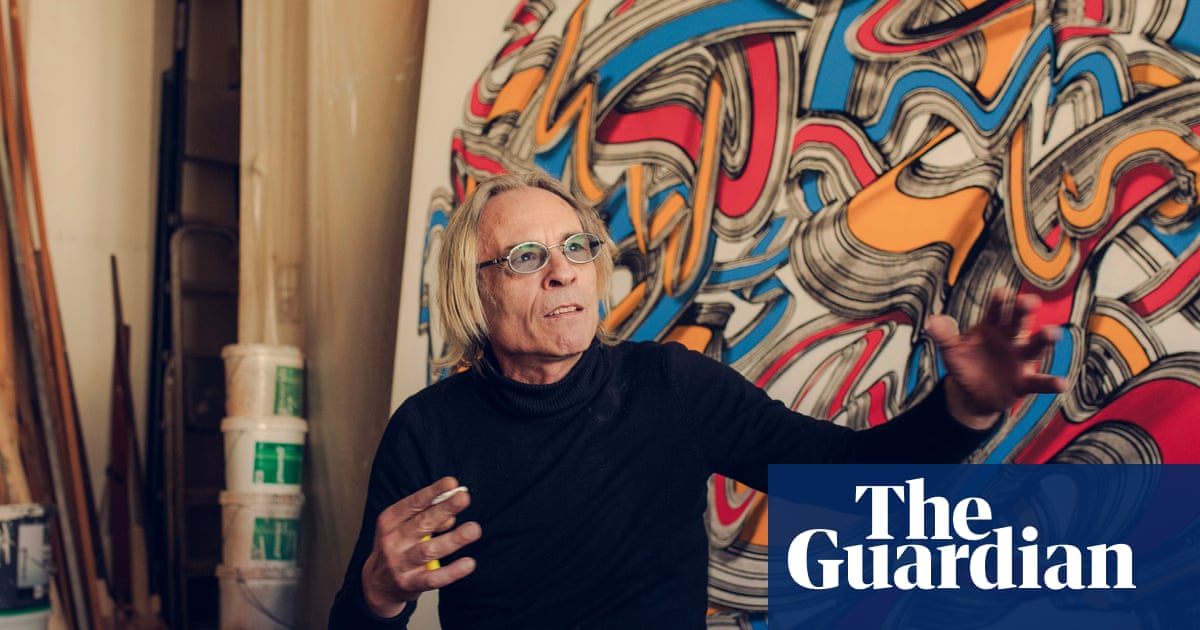

I love Rothko. Standing in front of his paintings always feels, to me, like an almost religious experience. The emotion in his work is astonishing, transcendent. This story has brought out two categories of people that I’ll admit I struggle with: people who don’t get the work of Mark Rothko, and people who dislike kids.

The thing about the first group of people is that their inability to connect with Rothko’s abstract expressionism often seems to make them cross. They rarely say, with any humility, “Oh, I don’t really get it, but perhaps I need to see it in person”, or “I can see it means a great deal to some people, but frankly it leaves me cold.” Instead, they can be a bit crotchety and defensive, hence the predictable plethora of snark in relation to this story: “Damaged? How can anyone tell?”; “It looks like a child painted it in the first place”; “It’s just a bunch of rectangles”; “Emperor’s new clothes” etc, etc.

As for the second group of people: it’s the usual calls for children to be banned from public spaces. They shouldn’t be allowed into galleries if they can’t behave, and their parents should be made to pay – that sort of thing. Although these ostensibly seem like two very different, frankly contradictory, lines of thinking – “modern art is rubbish” versus “galleries are sacred spaces” – I have come to realise that these sentiments are interlinked.

Children respond instinctively to art. They have not built up defences, or preconceptions about it, and the earlier you take them to galleries and expose them to different styles and mediums, the more open and receptive they will be to things that are experimental, unusual or transgressive. Their wild, expressionistic little souls are not bogged down by the fusty notion that good art has to be figurative. Have you seen their drawings? And they themselves are chaos personified. Like the splatters on a Pollock, they appear anarchic, but they have their own internal logic.

Children explore the world through touch. My boy loves to scratch his fingers against woodchip wallpaper, to stand with his palms flat against the rough bark of a tree. Anyone familiar with kids will be able to imagine what went through that child’s mind as they stood in front of Grey, Orange on Maroon, No 8. Something about the unvarnished, slightly chalky surface of the paint made them want to feel it. And so they did. Arguably, in doing so, they connected with the work of Rothko on a deeper level than many adults.

I’m not being entirely serious, but what I do believe is that the people who love art the most have somehow managed to retain that childish spirit of openness and curiosity into adulthood, and that spirit is precious. We need it, especially, for the next generation of artists, which is why the gallery must remain an inclusive place. No museum or gallery would seriously consider banning children. On the contrary, they tend to be ridiculously kind and understanding about these accidents.

“Every museum and gallery thinks hard about how to balance meaningful physical access to artworks and objects with keeping them safe. I’d say most have the balance right, but accidents can still happen,” the curator and writer Maxwell Blowfield said in the aftermath of the damage. “It’s impossible to prevent every potential incident, from visitors of all ages. Thankfully, things like this are very rare compared to the millions of visits taking place every day.” Meanwhile, the museum that lost the 3,500-year-old jar used it as a “teaching opportunity”, and invited its four-year-old former nemesis back to the museum with his family to see how the repairs were going.

There’s a loveliness to that. Perhaps, rather than charge the parents, the museum in Rotterdam will get its insurance payout and do something similar. Either way, I hope that the child wasn’t made to feel too bad. Perhaps it’ll be a funny story that the parents tell someday, and I bet they watch their child a bit more closely in future.

I don’t want to add to the shame they are probably already feeling, but I do wonder if it’s time modern parents had a think about rehabilitating the much-maligned toddler reins of the 1980s and 90s, even if just for occasional use. Some kids are fine in galleries, but others are whirlwinds who need keeping in check. My son loves running through Tate Modern, but to avoid him careening head first into the Joan Mitchell triptych, I’m wondering if I should pick up a pair before our next visit.

-

Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett is a Guardian columnist. The Republic of Parenthood book will be published this summer

19 hours ago

9

19 hours ago

9